The Atlantic Slave Trade

Part 4 Abolitionists

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.

In Western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest

Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first European law abolishing colonial slavery in 1542, although it was not to last (to 1545). In the 17th century, Quaker and evangelical religious groups condemned it as un-Christian; in the 18th century, rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment criticized it for violating the rights of man. Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, they had little immediate effect on the centers of slavery: the West Indies, South America, and the Southern United States. The Somersett’s case in 1772 that emancipated a slave in England helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Britain banned the importation of African slaves in its colonies in 1807, and the United States followed in 1808. Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the French colonies abolished it 15 years later, while slavery in the United States was abolished in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The court case of 1569 involving Cartwright who had bought a slave from Russia ruled that English law could not recognize slavery. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments, but was upheld by the Lord Chief Justice in 1701 when he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce later took on the cause of abolition in 1787 after the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which he led the parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. He continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, which he lived to see in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in Britain at the beginning of the 17th century. But by the 18th century, traders began to import African and Indian and East Asian slaves to London and Edinburgh to work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians were documented in colonial records. They were not bought or sold in London, and their legal status was unclear until 1772, when the case of a runaway slave named James Somersett forced a legal decision. The owner, Charles Steuart, had attempted to abduct him and send him to Jamaica to work on the sugar plantations. While in London, Somersett had been baptized

and his godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result

Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King’s Bench, had to judge whether the abduction was legal or not under English Common Law, as there was no legislation for slavery in England.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772 Mansfield declared: “Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.” Although the exact legal implications of the judgment are actually unclear when analyzed by lawyers, it was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law in England. While no authority could be applied on slaves entering English soil, the decision did not apply to other territories. The Somersett’s case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English speaking world, and helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. After reading about the Somersett’s Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African in Scotland, left his master John Wedderburn. A similar case to Steuart’s was brought by Wedderburn in 1776, with the same result.

Despite the ending of slavery in Great Britain, slavery was a strong institution in the Southern Colonies of British America and the West Indian colonies of the British Empire. In

1785, English poet William Cowper wrote: “We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free, they touch our country, and their shackles fall. That’s noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, and let it circulate through every vein. By 1783, an anti-slavery movement was beginning among the British public. That year the first British abolitionist organization was founded by a group of Quakers. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the lifetime of the movement, in many ways leading the campaign. On 17 June 1783 the issue was formally brought to government by Sir Cecil Wray (Member of Parliament for Westminster), who presented the Quaker petition to parliament. Also in 1783, Dr Beilby Porteus issued a call to the Church of England to cease its involvement in the slave trade and to formulate a workable policy to draw attention to and improve the conditions of Afro-Caribbean slaves. The exploration of the African continent, by such British groups as the African Association (1788), promoted the abolitionists’ cause by showing Europeans that the Africans had legitimate, complex cultures. The African Association also had close ties with William Wilberforce, perhaps the most important political figure in the battle for abolition in the British Empire.

In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, referring to the Atlantic slave trade, the trafficking in slaves by British merchants who took manufactured goods from ports such as Bristol and Liverpool, sold or exchanged these for slaves in West Africa where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery, shipped the slaves to British colonies and other Caribbean countries or the American colonies, where they sold or exchanged them mainly to the Planters for rum and sugar, which they took back to British ports. This was the so-called Triangle trade because these mercantile merchants traded in three places each round-trip. Political influence against the inhumanity of the slave trade grew strongly in the late 18th century. Many people, some African, some European by descent, influenced abolition. Well known abolitionists in Britain included James Ramsay who had seen the cruelty of the trade at first hand, Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood who produced the “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?” medallion for the Committee, and other members of the Clapham Sect of evangelical reformers, as well as Quakers who took most of the places on the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, having been the first to present a petition against the slave trade to the British Parliament and who founded the predecessor body to the Committee. As Dissenters, Quakers were not eligible to become British MPs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, so the Anglican evangelist William Wilberforce was persuaded to become the leader of the parliamentary campaign. Clarkson became the group’s most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of information about the slave trade, gaining firsthand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

Mainly because of Clarkson’s efforts, a network of local abolition groups was established across the country. They campaigned through public meetings and the publication of pamphlets and petitions. One of the earliest books promoted by Clarkson and the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was the autobiography of the freed slave

Olaudah Equiano. The movement had support from such freed slaves, from many denominational groups such as Swedenborgians, Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and others, and reached out for support from the new industrial workers of the cities in the midlands and north of England. Even women and children, previously un-politicized groups, became involved in the campaign although at this date women often had to hold separate meetings and were ineligible to be represented in the British Parliament, as indeed were the majority of the men in Britain.

One particular project of the abolitionists was the negotiation with African chieftains for the purchase of land in West African kingdoms for the establishment of ‘Freetown’ – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire and the United States, back in West Africa. This privately negotiated settlement, later part of Sierra Leone eventually became protected under a British Act of Parliament in 1807–8, after which British influence in West Africa grew as a series of negotiations with local Chieftains were signed to stamp out trading in slaves. These included agreements to permit British navy ships to intercept Chieftains’ ships to ensure their merchants were not carrying slaves.

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to the Dutch-controlled Surinam as part of a military force sent out to the maroon slaves living in the inlands. Stedman witnessed the oppressive tactics used against the slaves during the rebellion lead by coffy on the island. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It became part of a large body of abolitionist literature

The Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire. The Act imposed a fine of £100 for every slave found aboard a British ship. Such a law was bound to be eventually passed, given the increasingly powerful abolitionist movement. The timing might have been connected with the Napoleonic Wars raging at the time. At a time when Napoleon took the retrograde decision to revive slavery which had been abolished during the French Revolution and to send his troops to re-enslave the people of Haiti and the other French Caribbean possessions, the British prohibition of the slave trade gave the British Empire the moral high ground.

The act’s intention was to entirely outlaw the slave trade within the British Empire, but the trade continued and captains in danger of being caught by the Royal Navy would often throw slaves into the sea to reduce the fine. In 1827, Britain declared that participation in

the slave trade was piracy and punishable by death. Between 1808 and 1860, the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard. Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, for example against “the usurping King of Lagos”, deposed in 1851.

In 1841 Oba Akitoye ascended on the throne of Lagos and tried to bring an end to slave trade by placing a ban on the act. Lagos merchants, most notably Madam Tinubu, resisted the ban, deposed the king and installed his brother Oba Kosoko. Oba Akitoye, while on exile, met with the British, and got their backing to regain his throne. In 1851 he was reinstalled Oba of Lagos. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.

After the 1807 act, slaves were still held, though not sold, within the British Empire. In the 1820s, the abolitionist movement again became active, this time campaigning against the institution of slavery itself. In 1823 the first Anti-Slavery Society was founded in Britain. Many of the campaigners were those who had previously campaigned against the slave trade. Sam Sharpe contributed to the abolition of slavery with his Christmas rebellion in Jamaica in 1831. The rebellion caused two detailed Parliamentary Inquiries which eventually led combined with other events to the abolition of slavery.

On 28 August 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act was given Royal Assent, which paved the way for the abolition of slavery within the British Empire and its colonies. On 1 August 1834, all slaves in the British Empire were emancipated, but they were indentured to their former owners in an apprenticeship system which was abolished in two stages; the first set of apprenticeships came to an end on 1 August 1838, while the final apprenticeships were scheduled to cease on 1 August 1840, six years later.

On 1 August 1834, an unarmed group of mainly elderly Negroes being addressed by the Governor at Government House in Port of Spain, Trinidad, about the new laws, began chanting: “Pas de six ans. Point de six ans” (“Not six years. No six years”), drowning out the voice of the Governor. Peaceful protests continued until a resolution to abolish apprenticeship was passed and de facto freedom was achieved. Full emancipation for all was legally granted ahead of schedule on 1 August 1838, making Trinidad the first British colony with slaves to completely abolish slavery. The government set aside £20 million to cover compensation of slave owners across the Empire, but the former slaves received no compensation or reparations.

In 1839, a successor organization to the Anti-Slavery Society was formed, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which worked to outlaw slavery in other countries and also to pressure the government to help enforce the suppression of the slave trade by declaring slave traders pirates and pursuing them. The world’s oldest international human rights organization, it continues today as Anti-Slavery International.

France

As in other “New World” colonies, the Atlantic slave trade provided the French colonies with manpower for the sugar cane plantations. The French West Indies included Anguilla (briefly), Antigua and Barbuda (briefly), Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haïti, Montserrat (briefly), Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Eustatius (briefly), St Kitts and Nevis (St Kitts, but not Nevis), Trinidad and Tobago (Tobago only), Saint Croix (briefly), Saint-Barthélemy (until 1784 when became Swedish for nearly a century), the northern half of Saint Martin, and the current French overseas départements of Martinique and Guadeloupe in the Caribbean sea.

The slave trade was regulated by Louis XIV’s Code Noir. The revolt of slaves in the largest French colony of St. Domingue in 1791 was the beginning of what became the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture. The institution of slavery was first abolished in St. Domingue in 1793 by Sonthonax, who was the Commissioner sent to St. Domingue by the Convention, after the slave revolt of 1791, in order to safeguard the allegiance of the population to revolutionary France. The Convention, the first elected Assembly of the First

Republic (1792–1804), on the 4th of February 1794, under the leadership of

Maxmilien Robespierre, abolished slavery in law in France and its colonies. The abolition decree stated that “the Convention declares the slavery of the Blacks abolished in all the colonies; consequently, all men, irrespective of colour, living in the colonies are French citizens and will enjoy all the rights provided by the Constitution. “Abbé and the Society of the Friends of the Blacks (Société des Amis des Noirs), led by Jacques Pierre Brissot, were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole. The first article of the law stated that “Slavery was abolished” in the French colonies, while the second article stated that “slave-owners would be indemnified” with financial compensation for the value of their slaves. The constitution of France passed in 1795 included in the declaration of the Rights of Man that slavery was abolished.

However, Napoleon did not include any declaration of the Rights of Man in the Constitution promulgated in 1799, and decided to re-establish slavery after becoming First

Consul, promulgating the law of 20 May 1802 and sending military governors and troops to the colonies to impose it. On 10 May 1802, Colonel Delgrès launched a rebellion in Guadeloupe against Napoleon’s representative, General Richepanse. The rebellion was repressed, and slavery was re-established. The news of this event sparked the rebellion that led to the loss of the lives of tens of thousands of French soldiers, a greater loss of civilian lives, and Haïti’s gaining independence in 1804, and the consequential loss of the second most important French territory in the Americas, Louisiana, which was sold to the United States of America.

But it also is true that an abolitionist movement had taken root among the fashionable in Paris, headed by Madame de Staël and the Marquis de Lafayette. It was built on admiration of the English abolitionists, a rise of Christian morality, and a cult of le bon nègre. They began to circulate petitions and pamphlets. Prominent French writers led the opposition to the change, with racist diatribes against Africans.

When the

Duc de Broglie became prime minister, he brought abolitionist sympathies and opinions with him into the government. In 1817 the French government published a decree curtailing the slave trade to French colonies, but the enterprising merchants of Nantes and Bordeaux simply switched their destinations to Cuba.

The entire slave trade finally was declared illegal in France in March 1818. But that merely converted a tolerated trade to a clandestine one. With the local banks and political interests dominated by slave traders and their money and marriage ties, there was little hope of enforcement. French officers expelled from the Navy after the Restoration had taken up the slave trade. Their comrades still in the fleet turned a blind eye to their activities, or were easily bribed to do so. The French filled in the market for slaves in Cuba and Brazil in place of the Spanish, who had foresaken the trade as immoral.

Twice as many ships left French ports on the slave trade in 1819 as had sailed the year before. In 1820, the British Navy’s annual report on the fleet’s work in interdicting the slave trade noted that the Americans were next to Britain in their “good intentions,” “sincerity,” and practical work to end the trade. Spain, Holland, and Portugal got bad grades. “But France, it is with deepest regret I mention it, has countenanced and encouraged the slave trade, almost beyond estimation or belief.” It was so bad that “France is engrossing nearly the whole of the slave trade,” and in the 12 months ending in September 1819 “60,000 Africans have been forced from their country, principally under the colours of France.” They were taken mostly to Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Cuba.

As late as 1825, slave chains and manacles could be openly purchased in Nantes. On average, French négriers in the 1820s brought in 4,000 slaves per annum. Guadeloupe was the center of this activity, absorbing 38,000 slaves from 1814-1830. Martinique followed with 24,000 and French Guiana with 14,000. “It was an unusual trade in that French merchants from Nantes continued to dominate the trade to the end and were the only Europeans still active in the trade after 1808.” As late as 1830, Nantes kept 80 ships engaged in the slave trade.

The French, like the Americans, even after they had ended the slave trade refused to stand for the British Navy — the only maritime power large enough to police the Atlantic — boarding and searching their vessels. Under cover of national pride, the merchants of Nantes and Bordeaux continued to ship slaves even after the American government had, like the British, begun to use its authority to curb the trade.

In 1820, a British cruiser chased a French slaver, La Jeune Estele, whose captain, once he saw himself being overtaken, started throwing barrels overboard. In each was a pair of slave girls, age 12 to 14. Public opinion in Britain was shocked, but in France the people blamed the British.

In 1821, an over-zealous U.S. Navy lieutenant named Stockton seized four French-flagged vessels off Africa, convinced that they really were slavers from North America. He manned them with American crews and sailed them to Boston. But the French government was outraged — at least one of the vessels, La Jeune Eugénie, certainly was French, and it was going for slaves. The French ambassador called on Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and loudly threatened war if satisfaction was not made. President Madison hastily backed down and assured the French that the Americans no longer would search vessels under French or any other foreign flag. Stockton’s suspicions were reasonable, however. Slave traders of other nations often sailed under the French flag to avoid British searches.

Only in 1830, under

Louis-Philippe, was the slave trade made a crime and punishment enforced. A treaty with Britain even allowed British naval searches of French vessels in certain cases. Yet as late as 1848, recently imported slaves from West Africa were found on Martinique and Guadeloupe.

During the 1840s, the government in Paris talked of the eventuality of emancipation, but it always found a reason not to act. One common excuse was that the government was too cash-strapped to pay the slave-owners the compensation they deserved for the loss of their property.

Slavery finally was abolished in Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, and Réunion by the government that came to power after the 1848 revolution, spurred by slave uprisings in the colonies. A year later legislation passed granting the owners of France’s 248,560 slave’s compensation from a sum of $120 million francs.

Even the end was not really the end. From 1850 to 1870 some 18,400 Africans were carried to the French West Indies illegally, probably by Cuban slavers.

Figures are from Hugh Thomas, “The Slave Trade,” Simon & Schuster, 1997. The numbers necessarily are estimates, but historians are in broad agreement about them. There’s a “low” and a “high” figure for African slavery, and Thomas’ numbers represent the low figure. But the overall comparison does not change much if you use the (earlier) higher numbers: Slaves delivered to French West Indies come in as 1,635,700, compared to 559,800 for British North America and the U.S.

Spain

A Puerto Rican planter, Julio Vizcarrando, became the main figure in the Spanish abolitionist movement. He organized the first meeting of the Sociedad Abolicionista Española in Madrid (1864). Two other Puerto Ricans were involved (JosñAcosta and Joaquín Sanromá). Spanish liberals (Emilio Castelar, Juan Valera, Segimundo Moret, Nanuel Vecerra, and Nicolás Salmerón). Vizcarrando proved particularly important because he was so knowledgeable, both about slavery and the United States. He was married to Harriet Brewster of Philadelphia, an accomplished agitator for abolition. Vizcarrando has already freed his slaves, spoke publically against slavery, and set up a house of charity in San Juan. He adopted the same emblem for the Spanish abolition movement that had been used in Britain–a chained slave praying for deliverance. He helped establish branches in Barcelona, León, Saragossa, and Seville. He helped found a socially oriented journal–the Revista Hispano-Americano. The first issue carried an impassioned plea for ending the Cuban slave trade as the first step in colonial reforms. Committee’s organized in Spanish began asking basic questions about slavery. This showed how the American and British abolitionist campaigns had made little impact in the Iberian Peninsula, in part because the very traditional Spanish Catholic Church, unlike Protestant churches had played such a limited role in the abolitionist movement.

Spain lost most of its American Empire in the early 19th century. This reduced, but did not end the Spanish interest in the slave trade. It retained Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean. And Cuba was a particularly valuable colony as a result of the slave-based sugar industry. Spain finally signed a treaty with Britain abolishing the slave trade,

granting Britain the right to search Spanish-flag vessels suspected of slaving, it established a Mixed Commissions, authorising vessels equipped for the slave trade be condemned and broken up, and declaring that slaves liberated by the Mixed Commission should be delivered to the government whose cruiser made the capture (1835). It did not end, however, Spanish slavers trying to smuggle slaves to the Caribbean, primarily Cuba.

While Spain officially ended the slave trade (1835), slavery continued on the two remaining Spanish colonies in the America, Cuba and Puerto Rico. In fact the slave trade did not end. Slavers continued delivering captive slaves to both islands. The relatively small Spanish Navy made no serious effort to stop the slavers. And Spanish officials on the two islands commonly turned a blind eye on the traffic. Cuba is one of the largest Caribbean islands and has large flat areas ideal for sugar plantations. No country is more perfectly suited for growing sugar cane. Cuba was by far the most important with its productive sugar plantations. Puerto Rico was smaller island with less land suitable for plantation agriculture.

There were Spanish advocates of slavery. Their reasons being primarily economic. The planters, especially on Cuba, strongly advocated for a continuation of the system. There were also Spaniards who has racist attitudes toward blacks, although this currently was less pronounced than it had been in Britain and America. A popular journalist, José Ferrer de Couto Wrote, “The so-called slave trade is … the redemption of slaves and prisoners. He and others thought that the slaves were better off working on a Caribbean sugar plantation than in pagan, darkest Africa.

Abolitionist agitation and the national discussion which resulted emboldened the liberals in

the Courts. A motion for abolition was presented (May 6, 1865). Diputado Antonio María Fabie seconded the motion and delivered an impassioned oration. “The war in the United States is finished and, it being finished, slavery on the whole American continent can be taken as finished is it possible to keep … this institution in the Spanish dominions? I don’t think so. …. The Government must comply with its great obligations.” Interestingly, Fabie insisted that Spanish slavery was more benign than Anglo-Saxon (British and American) slavery. The result was not abolition, but the Cortes passed a strong bill with strong enforcement provisions to end the slave trade (1866). Before the bill could be promulgated, the Sergeant’s Revolt broke out which terrified the Queen and in the ensuing disorder, the Courts was suspended and the Queen turned to General Narváez.

A commission of Puerto Rican and Cuban liberals arrived in Madrid after the Spanish Army had restored order. General Narváez allowed them to meet with the Colonies Minister, Alehandro de Castro. The Puerto Rican representatives eventually proposed abolition. The Cubans were shocked. While not defending slavery, the Cubans wanted a more gradual approach and advocated political power for the creoles as first step. This would be followed by gradual emancipation over 7 year’s about compensation to the planters. They discussed an average figure of $450 per slave. The Commission discussed other matters, including Chinese labour. As the slave trade had been outlawed, the planters had begun importing Chinese labour. At the time the Commission met, there were about 100,000 Chinese labourers on Cuba. The Commission adjourned (April 1867). No actual actions followed from the discussions. General Narváez was prepared to allow the discussions, but not to take any actual steps toward abolition. And stridently pro-slavery Captain General, General Francisco Lersundi was put in place on Cuba. Lersundi was an ex-Caralist and Minister of War who was best known for supressing an 1848 revolt.

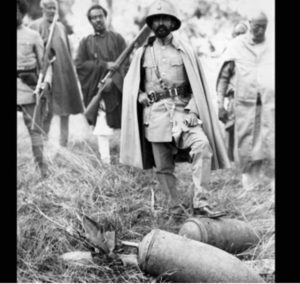

The first major armed action was the War of the Ten Years (1868-1878). A poorly equipped army of 8,000 Cubans fought a valiant struggle against a well-armed Spanish army which suffered some 80,000 casualties. The revolutionaries which failed to fight a centrally organized campaign finally had to give up with the Pact of the Trench, although General Antonio Maceo issued the protest of Baraguá.

Unsuspecting Queen Isabella travelled to Spain to sign an alliance with Emperor Napoleon III (1808-73). Admiral Juan Bautista Topete y Carballo (1821-85) used the occasion to issue a revolutionary proclamation at Cadiz (September 18, 1868). Popular uprisings broke out in Madrid and other major cities. Army oligarchs led by Francisco Serrano y Domínguez led the revolution of 1868. Queen Isabella immediately returned. So did exiled liberal generals. This included Juan Prim y Prats (1814-70). The two sides massed their forces. Rebel forces led by General Francisco Serrano (1810-85) decisively defeated the Royalists commanded by General Manuel Pavia y Lacy (1814-96) at the Battle of Alcolea, near Cordoba (September 28, 1868). The Queen had no choice but to seek refuge in France. The rebels declared her deposed. The rebels formed a provisional government which rescinded the reactionary laws and proceeded to take rake many long-advocated liberal measures. They abolished the Jesuits and other religious orders, enacted universal suffrage, and proclaimed freedom of the press. The provisional government was led by Serrano and Prim. They called for a constituent assembly (Courts). The Courts promulgated a new constitution which continued a monarchical government. The new government oversaw what was perhaps the most progressive, democratic eras in Spain during the 19th century. The abolitionist movement had an increasing influence on the Spanish public. Mass demonstrations were organized Perhaps 15,000 people demonstrated in Madrid (1873). Moret’s anti-slavery law was a compromise approach. It instituted a harsh apprenticeship system as the first step toward freedom for the freed slaves. Full freedom was set for 1886. Spain’s revolutionary process brought emancipation to Puerto Rico (1873). Slavery ended in Cuba after the conservative restoration of the Bourbon monarchy (1874-76) and the truce ending the Ten Years War (1878).

United States

North

In eleven States constituting the American South, slavery was a social and powerful economic institution, integral to the agricultural economy. By the 1860 United States Census, the slave population in the United States had grown to four million. American abolitionism labored under the handicap that it was accused of threatening the harmony of North and South in the Union. The abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers such as William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society; writers such as John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe; former slaves such as Frederick Douglass; and free blacks such as brothers Charles Henry Langston and John Mercer Langston, who helped found the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.

The 1860 presidential victory of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the spread of slavery to the Western United States, marked a turning point in the movement. Convinced that their way of life was threatened, the Southern states seceded from the Union, which led to the American Civil War. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves held in the Confederate States; the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1865) prohibited slavery throughout the country.

The first American movement to abolish slavery came in the spring of 1688 when German and Dutch Quakers of Mennonite descent in Germantown, Pennsylvania (now part of Philadelphia) wrote a two-page condemnation of the practice and sent it to the governing bodies of their Quaker church, the Society of Friends. Though the Quaker establishment took no immediate action, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery, was an unusually early, clear and forceful argument against slavery and initiated the process that finally led to the banning of slavery in the Society of Friends (1776) and in the state of Pennsylvania (1780).

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American abolition society, formed 14 April 1775, in Philadelphia, primarily by Quakers who had strong religious objections to slavery. The society ceased to operate during the Revolution and the British occupation of Philadelphia. After the Revolution, it was reorganized in 1784, with Benjamin Franklin as its first president. Rhode Island Quakers, associated with Moses Brown, co-founder of Brown University, and who also settled at Uxbridge, Massachusetts prior to 1770, were among the first in America to free slaves. Benjamin Rush was another leader, as were many Quakers. John Woolman gave up most of his business in 1756 to devote himself to campaigning against slavery along with other Quakers. The first article published in what later became the United States advocating the emancipation of slaves and the abolition of slavery was allegedly written by Thomas Paine. Titled “African Slavery in America”, it appeared on 8 March 1775 in the Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, more popularly known as The Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Museum.

Through the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 under the Congress of the Confederation, slavery was prohibited in the territories north west of the Ohio River. By 1804, abolitionists succeeded in passing legislation that would eventually (in conjunction with the 13th amendment) emancipate the slaves in every state north of the Ohio River and the Mason-Dixon Line. However, emancipation in the Free states was so gradual that both New York and Pennsylvania listed slaves in their 1840 census returns, and a small number of black slaves (18) were held in New Jersey in 1860.

The principal organized bodies to advocate this reform were the Pennsylvania Antislavery Society and the New York Manumission Society. The last was headed by powerful politicians: John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, later Federalists and Aaron Burr, later Democratic-Republican Vice-President of the United States. That bill did not pass, because of controversy over the rights of freed slaves; every member of the Legislature, but one, voted for some version of it. New York did enact a bill in 1799, which did end slavery over time, but made no provision for the freedmen. New Jersey in 1804 was the last northern state to enact the gradual elimination slavery (again in a gradual fashion); there were still eighteen “perpetual apprentices” in New Jersey in the 1860 Census. Despite the actions of abolitionists, free blacks were subject to racial segregation in the North.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, agreement was reached that allowed the Federal government to abolish the importation of slaves into the United States, but not prior to 1808. By that time, all the states had passed individual laws abolishing or severely limiting the international buying or selling of slaves. The importation of slaves into the United States was officially banned on January 1, 1808. But its internal slave trade carried on.

After 1776, Quaker and Moravian advocates helped persuade numerous slaveholders in the Upper South to free their slaves. Manumissions increased for nearly two decades. Many individual acts of manumission freed thousands of slaves in total. Slaveholders freed slaves in such number that the percentage of free Negroes in the Upper South increased sharply from one to ten percent, with most of that increase in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. By 1810 three-quarters of blacks in Delaware were free. The most notable of

individuals was Robert Carter III of Virginia, who freed more than 450 people by “Deed of Gift”, filed in 1791. This number was more slaves than any single American had freed or would ever free. Often slaveholders came to their decisions by their own struggles in the Revolution; their wills and deeds frequently cited language about the equality of men supporting their manumissions. Slaveholders were also encouraged to do so because the economics of the area was changing. They were shifting from labor-intensive tobacco culture to mixed crop cultivation and did not need as many slaves.

The free black families began to thrive, together with African Americans free before the Revolution, mostly descendants of unions between working class white women and African men. By 1860, in Delaware 91.7 percent of the blacks were free, and 49.7 percent of those in Maryland. These first free families often formed the core of artisans, professionals, preachers and teachers in future generations.

During the Congressional debate on the 1820 Tallmadge Amendment, which sought to limit slavery in Missouri as it became a state, Rufus King declared that “laws or compacts imposing any such condition [slavery] upon any human being are absolutely void, because contrary to the law of nature, which is the law of God, by which he makes his ways known to man, and is paramount to all human control.” The amendment failed and Missouri became a slave state. According to historian David Brion Davis, this may have been the first time in the world that a political leader openly attacked slavery’s perceived legality in such a radical manner.

Beginning in the 1830s, the U.S. Postmaster General refused to allow the mails to carry abolition pamphlets to the South. Northern teachers suspected of abolitionism were expelled from the South, and abolitionist literature was banned. Southerners rejected the denials of Republicans that they were abolitionists. They pointed to John Brown’s attempt in 1859 to start a slave uprising as proof that multiple Northern conspiracies were afoot to ignite bloody slave rebellions. Although some abolitionists did call for slave revolts, no evidence of any other Brown-like conspiracy has been discovered. The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, “Northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests”. However, many conservative Northerners were uneasy at the prospect of the sudden addition to the labor pool of a huge number of freed laborers who were used to working for very little, and thus seen as being willing to undercut prevailing wages. The famous, “fiery” Abolitionist, Abby Kelley Foster, from Massachusetts, was considered an “ultra” abolitionist who believed in full civil rights for all black people. She held to the views that the freed slaves would colonize Liberia. Parts of the anti-slavery movement became known as “Abby Kellyism”. She recruited Susan B Anthony to the movement.

The Second Great Awakening of the 1820s and 1830s in religion inspired groups that undertook many types of social reform. For some that meant the immediate abolition of slavery because it was a sin to hold slaves and a sin to tolerate slavery. “Abolitionist” had

several meanings at the time. The followers of William Lloyd Garrison, including Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass, demanded the “immediate abolition of slavery”, hence the name. A more pragmatic group of abolitionists, like Theodore Weld and Arthur Tappan, wanted immediate action, but that action might well be a program of gradual emancipation, with a long intermediate stage. “Antislavery men”, like John Quincy Adams, did not call slavery a sin. They called it an evil feature of society as a whole. They did what they could to limit slavery and end it where possible, but were not part of any abolitionist group. For example, in 1841 Adams represented the Amistad African slaves in the Supreme Court of the United States and argued that they should be set free. In the last years before the war, “antislavery” could mean the Northern majority, like Abraham Lincoln, who opposed expansion of slavery or its influence, as by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, or the Fugitive Slave Act. Many Southerners called all these abolitionists, without distinguishing them the Garrisonians.

Historian James Stewart (1976) explains the abolitionists’ deep beliefs: “All people were equal in God’s sight; the souls of black folks were as valuable as those of whites; for one of God’s children to enslave another was a violation of the Higher Law, even if it was sanctioned by the Constitution.”

Slave owners were angry over the attacks on what some Southerners (including the politician John C. Calhoun) referred to as their peculiar institution of slavery. Starting in the 1830s, there was a vehement and growing ideological defense of slavery. Slave owners claimed that slavery was a positive good for masters and slaves alike, and that it was explicitly sanctioned by God. Biblical arguments were made in defense of slavery by religious leaders such as the Rev. Fred A. Ross and political leaders such as Jefferson Davis. There were Southern biblical interpretations that directly contradicted those of the abolitionists, such as the theory that a curse on Noah’s son Ham and his descendants in Africa was a justification for enslavement of blacks.

A radical shift came in the 1830s, led by William Lloyd Garrison, who demanded “immediate emancipation, gradually achieved”. That is, he demanded that slave-owners repent immediately, and set up a system of emancipation. Theodore Weld, an evangelical minister, and Robert Purvis, a free African American, joined Garrison in 1833 to form the American Anti-Slavery Society. The following year Weld encouraged a group of students at Lane Theological Seminary to form an anti-slavery society. After the president, Lyman Beecher, attempted to suppress it, the students moved to Oberlin College. Due to the students’ anti-slavery position, Oberlin soon became one of the most liberal colleges and accepted African American students. Along with Garrison, were Northcutt and Collins as proponents of immediate abolition? These two ardent abolitionists felt very strongly that it could not wait and that action needed to be taken right away. Abby Kelley Foster became an “ultra abolitionist.” and a follower of William Lloyd Garrison. She led Susan B. Anthony as well as Elizabeth Cady Stanton into the anti-slavery cause.

After 1840 “abolition” usually referred to positions like Garrison’s; it was largely an ideological movement led by about 3000 people, including free blacks and people of color,

many of whom, such as

Frederick Douglass, and Robert Purvis and James Forten in Philadelphia, played prominent leadership roles. Douglass became legally free during a two year stay in England, as British supporters raised funds to purchase his freedom from his American owner Thomas Auld, and also helped fund his abolitionist newspapers in the US. Abolitionism had a strong religious base including Quakers, and people converted by the revivalist fervor of the Second Great Awakening, led by Charles Finney in the North in the 1830s. Belief in abolition contributed to the breaking away of some small denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church.

Evangelical abolitionists founded some colleges, most notably Bates College in Maine and Oberlin College in Ohio. The well-established colleges, such as Harvard, Yale and Princeton, generally opposed abolition, although the movement did attract such figures as Yale president Noah Porter and Harvard president Thomas Hill.

In the North, most opponents of slavery supported other modernizing reform movements such as the temperance movement, public schooling, and prison- and asylum-building. They were split bitterly on the role of women’s activism.

Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison repeatedly condemned slavery for contradicting the principles of freedom and equality on which the country was founded. In 1854, Garrison wrote:

I am a believer in that portion of the Declaration of American Independence in which it is set forth, as among self-evident truths, “that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Hence, I am an abolitionist. Hence, I cannot but regard oppression in every form – and most of all, that which turns a man into a thing – with indignation and abhorrence. Not to cherish these feelings would be recreancy to principle. They, who desire me to be dumb on the subject of slavery, unless I will open my mouth in its defense, ask me to give the lie to my professions, to degrade my manhood, and to stain my soul. I will not be a liar, a poltroon, or a hypocrite, to accommodate any party, to gratify any sect, to escape any odium or peril, to save any interest, to preserve any institution, or to promote any object. Convince me that one man may rightfully make another man his slave, and I will no longer subscribe to the Declaration of Independence. Convince me that liberty is not the inalienable birthright of every human being, of whatever complexion or clime, and I will give that instrument to the consuming fire. I do not know how to espouse freedom and slavery together”.

The most influential abolitionist tract was Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), the best-selling novel

and play by

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Outraged by the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 (which made the escape narrative part of everyday news), Stowe emphasized the horrors that abolitionists had long claimed about slavery. Her depiction of the evil slave owner Simon Legree, a transplanted Yankee who kills the Christ-like Uncle Tom, outraged the North, helped sway British public opinion against the South, and inflamed Southern slave owners who tried to refute it by showing some slave owners were humanitarian

Daniel O’Connell, the Catholic leader of the Irish in Ireland, supported the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and in America. O’Connell had played a leading role in securing Catholic Emancipation (the removal of the civil and political disabilities of Roman Catholics in Great Britain and Ireland) and he was one of William Lloyd Garrison’s models. Garrison recruited him to the cause of American abolitionism. O’Connell, the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond, and the temperance priest Theobald Mathew organized a petition with 60,000 signatures urging the Irish of the United States to support abolition. O’Connell also spoke in the United States for abolition.

The Catholic Church in America had long ties in slaveholding Maryland and Louisiana. Despite a firm stand for the spiritual equality of black people, and the resounding condemnation of slavery by Pope Gregory XVI in his bull In Supremo Apostolatus issued in 1839, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, like most of America, to avoid confrontation with slaveholding interests. In 1842, the Archbishop of New York while denouncing slavery objected to O’Connell’s petition if authentic as

unwarranted foreign interference. The Bishop of Charleston declared that, while Catholic tradition opposed slave trading, it had nothing against slavery. However, in 1861, the Archbishop of New York wrote to Secretary of War Cameron: “That the Church is opposed to slavery…Her doctrine on that subject is, that it is a crime to reduce men naturally free to a condition of servitude and bondage, as slaves.” No American bishop supported extra-political abolition or interference with state’s rights before the Civil War. During the Civil War, however, the Archbishop of New York, John Hughes, who was an ally of Lincoln and Seward would denounce Southern bishops as follows: “In their periodicals in New Orleans and Charleston, they have justified the attitude taken by the South on principles of Catholic theology, which I think was an unnecessary, inexpedient, and, for that matter, a doubtful if not dangerous position, at the commencement of so unnatural and lamentable a struggle.”

South

The institution remained solid in the South, however and that region’s customs and social beliefs evolved into a strident defense of slavery in response to the rise of a stronger anti-slavery stance in the North. In 1835 alone abolitionists mailed over a million pieces of anti-slavery literature to the south. In response southern legislators banned abolitionist literature and encouraged harassment of anyone distributing it.

Abolitionists included those who joined the American Anti-Slavery Society or its auxiliary groups in the 1830s and 1840s as the movement fragmented. The fragmented anti-slavery movement included groups such as the Liberty Party; the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society; the American Missionary Association; and the Church Anti-Slavery Society. Historians traditionally distinguish between moderate antislavery reformers or gradualists, who concentrated on stopping the spread of slavery, and radical abolitionists or immediatists, whose demands for unconditional emancipation often merged with a concern for black civil rights. However, James Stewart advocates a more nuanced understanding of the relationship of abolition and antislavery prior to the Civil War:

While instructive, the distinction between antislavery and abolition can also be misleading, especially in assessing abolitionism’s political impact. For one thing, slaveholders never bothered with such fine points. Many immediate abolitionists showed no less concern than did other white Northerners about the fate of the nation’s “precious legacies of freedom.” Immediatism became most difficult to distinguish from broader anti-Southern opinions once ordinary citizens began articulating these intertwining beliefs.

Anti-slavery people were outraged by the murder of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a white man and editor of an abolitionist newspaper on 7 November 1837, by a pro-slavery mob in Illinois. Nearly all Northern politicians rejected the extreme positions of the abolitionists; Abraham Lincoln, for example. Indeed many northern leaders including Lincoln, Stephen Douglas (the Democratic nominee in 1860), John C. Fremont (the Republican nominee in 1856), and Ulysses S. Grant married into slave owning southern families without any moral qualms.

Antislavery as a principle was far more than just the wish to limit the extent of slavery. Most Northerners recognized that slavery existed in the South and the Constitution did not allow the federal government to intervene there. Most Northerners favored a policy of gradual and compensated emancipation. After 1849 abolitionists rejected this and demanded it end immediately and everywhere. John Brown was the only abolitionist known to have actually planned a violent insurrection, though David Walker promoted the idea. The abolitionist movement was strengthened by the activities of free African-Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old Biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament.

African-American activists and their writings were rarely heard outside the black community; however, they were tremendously influential to some sympathetic white people, most prominently the first white activist to reach prominence, William Lloyd Garrison, who was its most effective propagandist. Garrison’s efforts to recruit eloquent spokesmen led to the discovery of ex-slave Frederick Douglass, who eventually became a prominent activist in his own right. Eventually, Douglass would publish his own, widely distributed abolitionist newspaper, the North Star.

In the early 1850s, the American abolitionist movement split into two camps over the issue of the United States Constitution. This issue arose in the late 1840s after the publication of The Unconstitutionality of Slavery by Lysander Spooner. The Garrisonians, led by Garrison and Wendell Phillips, publicly burned copies of the Constitution, called it a pact with slavery, and demanded its abolition and replacement. Another camp, led by Lysander Spooner, Gerrit Smith, and eventually Douglass, considered the Constitution to be an antislavery document. Using an argument based upon Natural Law and a form of social contract theory, they said that slavery existed outside of the Constitution’s scope of legitimate authority and therefore should be abolished.

Another split in the abolitionist movement was along class lines. The artisan republicanism of Robert Dale Owen and Frances Wright stood in stark contrast to the politics of prominent elite abolitionists such as industrialist Arthur Tappan and his evangelist brother Lewis. While the former pair opposed slavery on a basis of solidarity of “wage slaves” with “chattel slaves”, the Whiggish Tappans strongly rejected this view, opposing the characterization of Northern workers as “slaves” in any sense.

Many American abolitionists took an active role in opposing slavery by supporting the Underground Railroad. This was made illegal by the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Nevertheless, participants like Harriet Tubman, Henry Highland Garnet, Alexander Crummell, Amos Noë Freeman and others continued with their work. Abolitionists were particularly active in Ohio, where some worked directly in the Underground Railroad. Since the state shared a border with slave states, it was a popular place for slaves’ escaping across the Ohio River and up its tributaries, where they sought shelter among supporters who would help them move north to freedom. Two significant events in the struggle to destroy slavery were the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. In the South, members of the abolitionist movement or other people opposing slavery were often targets of lynch mob violence before the American Civil War.

Numerous known abolitionists lived, worked, and worshipped in Downtown Brooklyn, from Henry Ward Beecher, who auctioned slaves into freedom from the pulpit of Plymouth Church, to Nathan Egelston, a leader of the African and Foreign Antislavery Society, who also preached at Bridge Street AME and lived on Duffield Street. His fellow Duffield Street residents, Thomas and Harriet Truesdell were leading members of the Abolitionist movement. Mr. Truesdell was a founding member of the Providence Anti-slavery Society before moving to Brooklyn in 1851. Harriet Truesdell was also very active in the movement, organizing an antislavery convention in Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia. The Tuesdell’s lived at 227 Duffield Street. Another prominent Brooklyn-based abolitionist was Rev. Joshua Leavitt, trained as a lawyer at Yale who stopped practicing law in order to attend Yale Divinity School, and subsequently edited the abolitionist newspaper The Emancipator and campaigned against slavery, as well as advocating other social reforms. In 1841 Leavitt published his The Financial Power of Slavery, which argued that the South was draining the national economy due to its reliance on slavery.

John Brown

Historian Frederick Blue called John Brown “the most controversial of all nineteenth-century Americans.” When Brown was hanged after his attempt to start a slave rebellion in 1859, church bells rang, minute guns were fired, large memorial meetings took place throughout the North, and famous writers such as Emerson and Henry David Thoreau joined many Northerners in praising Brown. Whereas Garrison was a pacifist, Brown resorted to violence. Historians agree he played a major role in starting the war. Some historians regard Brown as a crazed lunatic while David S. Reynolds hails him as the man who “killed slavery, sparked the civil war, and seeded civil rights.” For Ken Chowder he is “the father of American terrorism.”

His famous raid in October 1859, involved a band of 22 men who seized the federal Harpers Ferry Armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, knowing it contained tens of thousands of weapons. Brown believed that the South was on the verge of a gigantic slave uprising and that one spark would set it off. Brown’s supporters George Luther Stearns, Franklin B. Sanborn, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, Samuel Gridley Howe and Gerrit Smith were all abolitionist members of the Secret Six who provided financial backing for Brown’s raid. Brown’s raid, says historian David Potter, “was meant to be of vast magnitude and to produce a revolutionary slave uprising throughout the South.” The raid was a fiasco. Not a single slave revolted. Lt. Colonel Robert E. Lee of the U.S. Army was dispatched to put down the raid, and Brown was quickly captured. Brown was tried for treason against Virginia and hanged. At his trial, Brown exuded a remarkable zeal and single-mindedness that played directly to Southerners’ worst fears. Few individuals did more to cause secession than John Brown, because Southerners believed he was right about an impending slave revolt. Shortly before his execution, Brown prophesied, “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away; but with Blood.”

Civil War

Union leaders identified slavery as the social and economic foundation of the Confederacy, and from 1862 were determined to end that support system. Meanwhile pro-Union forces gained control of the Border States and began the process of emancipation in Maryland, Missouri and West Virginia. Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January 1863, and in the next 24 months it effectively ended slavery throughout the Confederacy. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment (ratified in Dec. 1865) officially ended slavery in the United States, and freed the 50,000 or so remaining slaves in the Border States.

It must never be understated the important part that the abolitionists played in the abolishment of slavery and the final end to the Atlantic slave trade. They fought for the abolishment of laws which supported the cargo of human slaves from Africa to the Americas and Caribbean. Their efforts lead to the formulation of groups and organisations that up to today are fighting against the illegal trade of human trafficking one such organisation is the Anti-Slavery International, founded in 1839; this is the world’s oldest international human rights organization and works to eliminate all forms of slavery around the world. We do hope that humanity will always succeed in the battle of good over this evil trade and that civilization will never allow itself to fall back into the abyss of evil.

Watch the videos below to give an insight into the trials faced by black peoples after emancipation.

American Aftermath

[/emember_protected]

]]>

In Western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first European law abolishing colonial slavery in 1542, although it was not to last (to 1545). In the 17th century, Quaker and evangelical religious groups condemned it as un-Christian; in the 18th century, rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment criticized it for violating the rights of man. Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, they had little immediate effect on the centers of slavery: the West Indies, South America, and the Southern United States. The Somersett’s case in 1772 that emancipated a slave in England helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Britain banned the importation of African slaves in its colonies in 1807, and the United States followed in 1808. Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the French colonies abolished it 15 years later, while slavery in the United States was abolished in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The court case of 1569 involving Cartwright who had bought a slave from Russia ruled that English law could not recognize slavery. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments, but was upheld by the Lord Chief Justice in 1701 when he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.

In Western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first European law abolishing colonial slavery in 1542, although it was not to last (to 1545). In the 17th century, Quaker and evangelical religious groups condemned it as un-Christian; in the 18th century, rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment criticized it for violating the rights of man. Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, they had little immediate effect on the centers of slavery: the West Indies, South America, and the Southern United States. The Somersett’s case in 1772 that emancipated a slave in England helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. Pennsylvania passed An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1780. Britain banned the importation of African slaves in its colonies in 1807, and the United States followed in 1808. Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the French colonies abolished it 15 years later, while slavery in the United States was abolished in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The court case of 1569 involving Cartwright who had bought a slave from Russia ruled that English law could not recognize slavery. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments, but was upheld by the Lord Chief Justice in 1701 when he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.

William Wilberforce later took on the cause of abolition in 1787 after the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which he led the parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. He continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, which he lived to see in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in Britain at the beginning of the 17th century. But by the 18th century, traders began to import African and Indian and East Asian slaves to London and Edinburgh to work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians were documented in colonial records. They were not bought or sold in London, and their legal status was unclear until 1772, when the case of a runaway slave named James Somersett forced a legal decision. The owner, Charles Steuart, had attempted to abduct him and send him to Jamaica to work on the sugar plantations. While in London, Somersett had been baptized

William Wilberforce later took on the cause of abolition in 1787 after the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which he led the parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807. He continued to campaign for the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, which he lived to see in the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in Britain at the beginning of the 17th century. But by the 18th century, traders began to import African and Indian and East Asian slaves to London and Edinburgh to work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians were documented in colonial records. They were not bought or sold in London, and their legal status was unclear until 1772, when the case of a runaway slave named James Somersett forced a legal decision. The owner, Charles Steuart, had attempted to abduct him and send him to Jamaica to work on the sugar plantations. While in London, Somersett had been baptized  and his godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King’s Bench, had to judge whether the abduction was legal or not under English Common Law, as there was no legislation for slavery in England.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772 Mansfield declared: “Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.” Although the exact legal implications of the judgment are actually unclear when analyzed by lawyers, it was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law in England. While no authority could be applied on slaves entering English soil, the decision did not apply to other territories. The Somersett’s case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English speaking world, and helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. After reading about the Somersett’s Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African in Scotland, left his master John Wedderburn. A similar case to Steuart’s was brought by Wedderburn in 1776, with the same result.

Despite the ending of slavery in Great Britain, slavery was a strong institution in the Southern Colonies of British America and the West Indian colonies of the British Empire. In

and his godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King’s Bench, had to judge whether the abduction was legal or not under English Common Law, as there was no legislation for slavery in England.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772 Mansfield declared: “Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.” Although the exact legal implications of the judgment are actually unclear when analyzed by lawyers, it was generally taken at the time to have decided that the condition of slavery did not exist under English law in England. While no authority could be applied on slaves entering English soil, the decision did not apply to other territories. The Somersett’s case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English speaking world, and helped launch the movement to abolish slavery. After reading about the Somersett’s Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African in Scotland, left his master John Wedderburn. A similar case to Steuart’s was brought by Wedderburn in 1776, with the same result.

Despite the ending of slavery in Great Britain, slavery was a strong institution in the Southern Colonies of British America and the West Indian colonies of the British Empire. In  1785, English poet William Cowper wrote: “We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free, they touch our country, and their shackles fall. That’s noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, and let it circulate through every vein. By 1783, an anti-slavery movement was beginning among the British public. That year the first British abolitionist organization was founded by a group of Quakers. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the lifetime of the movement, in many ways leading the campaign. On 17 June 1783 the issue was formally brought to government by Sir Cecil Wray (Member of Parliament for Westminster), who presented the Quaker petition to parliament. Also in 1783, Dr Beilby Porteus issued a call to the Church of England to cease its involvement in the slave trade and to formulate a workable policy to draw attention to and improve the conditions of Afro-Caribbean slaves. The exploration of the African continent, by such British groups as the African Association (1788), promoted the abolitionists’ cause by showing Europeans that the Africans had legitimate, complex cultures. The African Association also had close ties with William Wilberforce, perhaps the most important political figure in the battle for abolition in the British Empire.

In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, referring to the Atlantic slave trade, the trafficking in slaves by British merchants who took manufactured goods from ports such as Bristol and Liverpool, sold or exchanged these for slaves in West Africa where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery, shipped the slaves to British colonies and other Caribbean countries or the American colonies, where they sold or exchanged them mainly to the Planters for rum and sugar, which they took back to British ports. This was the so-called Triangle trade because these mercantile merchants traded in three places each round-trip. Political influence against the inhumanity of the slave trade grew strongly in the late 18th century. Many people, some African, some European by descent, influenced abolition. Well known abolitionists in Britain included James Ramsay who had seen the cruelty of the trade at first hand, Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood who produced the “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?” medallion for the Committee, and other members of the Clapham Sect of evangelical reformers, as well as Quakers who took most of the places on the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, having been the first to present a petition against the slave trade to the British Parliament and who founded the predecessor body to the Committee. As Dissenters, Quakers were not eligible to become British MPs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, so the Anglican evangelist William Wilberforce was persuaded to become the leader of the parliamentary campaign. Clarkson became the group’s most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of information about the slave trade, gaining firsthand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

Mainly because of Clarkson’s efforts, a network of local abolition groups was established across the country. They campaigned through public meetings and the publication of pamphlets and petitions. One of the earliest books promoted by Clarkson and the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was the autobiography of the freed slave

1785, English poet William Cowper wrote: “We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free, they touch our country, and their shackles fall. That’s noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, and let it circulate through every vein. By 1783, an anti-slavery movement was beginning among the British public. That year the first British abolitionist organization was founded by a group of Quakers. The Quakers continued to be influential throughout the lifetime of the movement, in many ways leading the campaign. On 17 June 1783 the issue was formally brought to government by Sir Cecil Wray (Member of Parliament for Westminster), who presented the Quaker petition to parliament. Also in 1783, Dr Beilby Porteus issued a call to the Church of England to cease its involvement in the slave trade and to formulate a workable policy to draw attention to and improve the conditions of Afro-Caribbean slaves. The exploration of the African continent, by such British groups as the African Association (1788), promoted the abolitionists’ cause by showing Europeans that the Africans had legitimate, complex cultures. The African Association also had close ties with William Wilberforce, perhaps the most important political figure in the battle for abolition in the British Empire.

In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, referring to the Atlantic slave trade, the trafficking in slaves by British merchants who took manufactured goods from ports such as Bristol and Liverpool, sold or exchanged these for slaves in West Africa where the African chieftain hierarchy was tied to slavery, shipped the slaves to British colonies and other Caribbean countries or the American colonies, where they sold or exchanged them mainly to the Planters for rum and sugar, which they took back to British ports. This was the so-called Triangle trade because these mercantile merchants traded in three places each round-trip. Political influence against the inhumanity of the slave trade grew strongly in the late 18th century. Many people, some African, some European by descent, influenced abolition. Well known abolitionists in Britain included James Ramsay who had seen the cruelty of the trade at first hand, Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, Josiah Wedgwood who produced the “Am I Not A Man And A Brother?” medallion for the Committee, and other members of the Clapham Sect of evangelical reformers, as well as Quakers who took most of the places on the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, having been the first to present a petition against the slave trade to the British Parliament and who founded the predecessor body to the Committee. As Dissenters, Quakers were not eligible to become British MPs in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, so the Anglican evangelist William Wilberforce was persuaded to become the leader of the parliamentary campaign. Clarkson became the group’s most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of information about the slave trade, gaining firsthand accounts by interviewing sailors and former slaves at British ports such as Bristol, Liverpool and London.

Mainly because of Clarkson’s efforts, a network of local abolition groups was established across the country. They campaigned through public meetings and the publication of pamphlets and petitions. One of the earliest books promoted by Clarkson and the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was the autobiography of the freed slave  Olaudah Equiano. The movement had support from such freed slaves, from many denominational groups such as Swedenborgians, Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and others, and reached out for support from the new industrial workers of the cities in the midlands and north of England. Even women and children, previously un-politicized groups, became involved in the campaign although at this date women often had to hold separate meetings and were ineligible to be represented in the British Parliament, as indeed were the majority of the men in Britain.

One particular project of the abolitionists was the negotiation with African chieftains for the purchase of land in West African kingdoms for the establishment of ‘Freetown’ – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire and the United States, back in West Africa. This privately negotiated settlement, later part of Sierra Leone eventually became protected under a British Act of Parliament in 1807–8, after which British influence in West Africa grew as a series of negotiations with local Chieftains were signed to stamp out trading in slaves. These included agreements to permit British navy ships to intercept Chieftains’ ships to ensure their merchants were not carrying slaves.

Olaudah Equiano. The movement had support from such freed slaves, from many denominational groups such as Swedenborgians, Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and others, and reached out for support from the new industrial workers of the cities in the midlands and north of England. Even women and children, previously un-politicized groups, became involved in the campaign although at this date women often had to hold separate meetings and were ineligible to be represented in the British Parliament, as indeed were the majority of the men in Britain.

One particular project of the abolitionists was the negotiation with African chieftains for the purchase of land in West African kingdoms for the establishment of ‘Freetown’ – a settlement for former slaves of the British Empire and the United States, back in West Africa. This privately negotiated settlement, later part of Sierra Leone eventually became protected under a British Act of Parliament in 1807–8, after which British influence in West Africa grew as a series of negotiations with local Chieftains were signed to stamp out trading in slaves. These included agreements to permit British navy ships to intercept Chieftains’ ships to ensure their merchants were not carrying slaves.

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to the Dutch-controlled Surinam as part of a military force sent out to the maroon slaves living in the inlands. Stedman witnessed the oppressive tactics used against the slaves during the rebellion lead by coffy on the island. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It became part of a large body of abolitionist literature

The Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire. The Act imposed a fine of £100 for every slave found aboard a British ship. Such a law was bound to be eventually passed, given the increasingly powerful abolitionist movement. The timing might have been connected with the Napoleonic Wars raging at the time. At a time when Napoleon took the retrograde decision to revive slavery which had been abolished during the French Revolution and to send his troops to re-enslave the people of Haiti and the other French Caribbean possessions, the British prohibition of the slave trade gave the British Empire the moral high ground.

The act’s intention was to entirely outlaw the slave trade within the British Empire, but the trade continued and captains in danger of being caught by the Royal Navy would often throw slaves into the sea to reduce the fine. In 1827, Britain declared that participation in

In 1796, John Gabriel Stedman published the memoirs of his five-year voyage to the Dutch-controlled Surinam as part of a military force sent out to the maroon slaves living in the inlands. Stedman witnessed the oppressive tactics used against the slaves during the rebellion lead by coffy on the island. The book is critical of the treatment of slaves and contains many images by William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi depicting the cruel treatment of runaway slaves. It became part of a large body of abolitionist literature