The Scramble For Africa

African Colonialism Part 1

Introduction Video “The Division of Africa Berlin 1885”

The Scramble for Africa (1880-1900) also known as the Race for Africa or Partition

of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period. But it wouldn’t have happened except for the particular economic, social, and military evolution Europe was going through.

As a result of the heightened tension between European states in the last quarter of the 19th century, the partitioning of Africa may be seen as a way for the Europeans to eliminate the threat of a Europe-wide war over Africa. The latter half of the 19th century saw the transition from the “informal” imperialism of control through military influence and economic dominance to that of direct rule. Attempts to mediate imperial competition, such as the Berlin Conference (1884 – 1885) among the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the French Third Republic and the German Empire, failed to establish definitively the competing powers’ claims. Dispute over Africa was one of the factors leading to the First World War.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The opening of Africa to Western exploration and exploitation had begun in earnest at the end of the 18th century. By 1835, Europeans had mapped most of north-western Africa. Among the most famous of the European explorers was

David Livingstone,

who charted the vast interior and Serpa Pinto, who crossed both Southern Africa and Central Africa on a difficult expedition, mapping much of the interior of the continent. Arduous expeditions in the 1850s and 1860s by Richard Burton, John Speke and James Grant located the great central lakes and the source of the Nile. By the end of the century, Europeans had charted the Nile from its source, the courses of the Niger, Congo and Zambezi Rivers had been traced, and the world now realized the vast resources of Africa.

However, on the eve of the New Imperialist scramble for Africa, only ten per cent of the continent was under the control of Western nations. In 1875, the most important holdings were Algeria, whose conquest by France had started in the 1830s — despite Abd al-Qadir’s strong resistance and the Kabyles’ rebellion in the 1870s; the Cape Colony, held by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; and Angola, held by Portugal.

Leading Factors

There were several factors which created the impetus for the Scramble for Africa; most of these were to do with events in Europe rather than in Africa.

End of the Slave Trade .

Britain had had some success in halting the slave trade around the shores of Africa. But inland the story was different. Muslim traders from north of the Sahara and on the East Coast still traded inland, and many local chiefs were reluctant to give up the use of slaves. Reports of slaving trips and markets were brought back to Europe by various explorers, such as Livingstone, and abolitionists in Britain and Europe were calling for more to be done.

Exploration.

During the nineteenth century barely a year went by without a European expedition into Africa. The boom in exploration was triggered to a great extent by the creation of the African Association by wealthy Englishmen in 1788 (who wanted someone to ‘find’ the fabled city of Timbuktu and the course of the Niger River). As the century moved on, the goal of the European explorer changed, and rather than traveling out of pure curiosity they started to record details of markets, goods, and resources for the wealthy philanthropists who financed their trips.

Henry Morton Stanley.

A naturalized American (born in Wales) who of all the explorers of Africa is the one most closely connected to the start of the Scramble for Africa. Stanley had crossed the continent and located the ‘missing’ Livingstone, but he is more infamously known for his explorations on behalf of King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold hired Stanley to obtain treaties with local chieftains along the course of the River Congo with an eye to creating his own colony (Belgium was not in a financial position to fund a colony at that time). Stanley’s work triggered a rush of European explorers, such as Carl Peters, to do the same for various European countries.

Capitalism

The end of European trading in slaves left a need for commerce between Europe and Africa. Capitalists may have seen the light over slavery, but they still wanted to exploit the continent new ‘legitimate’ trade would be encouraged. Explorers located vast reserves of raw materials; they plotted the course of trade routes, navigated rivers, and identified population centers which could be a market for manufactured goods from Europe. It was a time of plantations and cash crops, dedicating the region’s workforce to producing rubber, coffee, sugar, palm oil, timber, etc. for Europe. And all the more enticing if a colony could be set up which gave the European nation a monopoly.

Steam Engines and Iron Hulled Boats.

In 1840 the Nemesis arrived at Macao, south China. It changed the face of international relations between Europe and the rest of the world. The Nemesis had a shallow draft (five feet), a hull of iron, and two powerful steam engines. It could navigate the non-tidal sections of rivers, allowing access inland, and it was heavily armed. Livingstone used a steamer to travel up the Zambezi in 1858, and had the parts transported overland to Lake Nyassa. Steamers also allowed Henry Morton Stanley and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza to explore the Congo.

Medical Advances

Africa, especially the western regions, was known as the ‘White Man’s Grave’ because of the danger of two diseases: malaria and yellow fever. During the eighteenth century only one in ten Europeans sent out to the continent by the Royal African Company survived. Six of the ten would have died in their first year. In 1817 two French scientists,

Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, extracted quinine from the bark of the South American cinchona tree. It proved to be the solution to malaria; Europeans could now survive the ravages of the disease in Africa. (Unfortunately yellow fever continued to be a problem – and even today there is no specific treatment for the disease.)

Politics

After the creation of a unified Germany (1871) and Italy (a longer process, but its capital relocated to Rome also in 1871) there was no room left in Europe for expansion. Britain, France and Germany were in an intricate political dance, trying to maintain their dominance, and an empire would secure it. France, which had lost two provinces to Germany in 1870, looked to Africa to gain more territory. Britain looked towards Egypt and the control of the Suez Canal as well as pursuing territory in gold rich southern Africa. Germany, under the expert management of Chancellor Bismarck, had come late to the idea of overseas colonies, but was now fully convinced of their worth. (It would need some mechanism to be put in place to stop overt conflict over the coming land grab.)

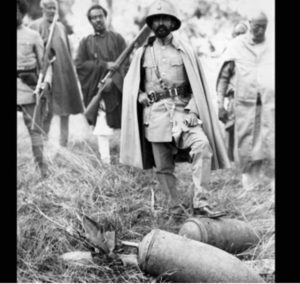

Military Innovation

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Europe was only marginally ahead of Africa in terms of available weapons as traders had long supplied them to local chiefs and many had stockpiles of guns and gunpowder. But two innovations gave Europe a massive advantage. In the late 1860s percussion caps were being incorporated into cartridges what previously came as a separate bullet, powder and wadding, was now a single entity, easily transported and relatively weather proof. The second innovation was the breach loading rifle. Older model muskets, held by most Africans, were front loaders, slow to use (maximum of three rounds per minute) and had to be loaded whilst standing. Breach loading guns, in comparison, had between two to four times the rates of fire, and could be loaded even in a prone position. Europeans, with an eye to colonization and conquest, restricted the sale of the new weaponry to Africa maintaining military superiority.

Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by “informal imperialism” and “civilization”, was also attractive to Europe’s ruling elites for economic and racial reasons. During a time when Britain’s balance of trade showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets due to the Long Depression (1873-1896), Africa offered Britain, Germany and other countries an open market that would garner it a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the metropolis than it sold overall. Britain, like most other industrial countries, had long since begun to run an unfavorable balance of trade (which was increasingly offset, however, by the income from overseas investments)

As Britain developed into the world’s first post-industrial nation, financial services became an increasingly important sector of its economy. Invisible financial exports, as mentioned, kept Britain out of the red, especially capital investments outside Europe, particularly to the developing and open markets in Africa, predominantly white settler colonies, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

In addition, surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap labor, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement to imperialism, of course, arose from the demand for raw materials unavailable in Europe, especially copper, cotton, rubber, tea, and tin, to which European consumers had grown accustomed and upon which European industry had grown dependent.

However, in Africa — exclusive of what would become the Union of South Africa in 1909 — the amount of capital investment by Europeans was relatively small, compared to other continents, before and after the 1884-85 Berlin Conference. Consequently, the companies involved in tropical African commerce were relatively small, apart from

Cecil Rhodes’ De Beers Mining Company, who had carved out Rhodesia for himself, as Léopold II would exploit the Congo Free State.

The Mad Rush Into Africa in the Early 1880s

Africa was treated in diplomacy at the time in the same manner as the New World Indians. Thus, by the middle 1800s, the Continent was considered disputed territory ripe for exploration, trade, and settlement. However, the continent except for the traditional posts along the coasts was essentially ignored. But, this state changed as a result of King Leopold of Belgium’s desire for glory.

In 1878,

King Léopold II of Belgium who had previously founded the International African Society in 1876 invited Stanley to join him in researching and ‘civilizing’ the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society was also formed, with more economic goals, but still closely related to the former society. Léopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic goals, with the African Society serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

Thus, from 1879 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo, this time not as a reporter, but as an envoy from Léopold with the secret mission to organize what would become known as the Congo Free State. In the meantime, French intelligence had discovered Leopold’s plans and was quickly engaging in its own

colonial exploration. French naval officer

Pierre de Brazza was dispatched to central Africa, traveled into the western Congo basin and raised the French flag over the newly-founded Brazzaville in 1881, in what is currently the Republic of Congo. Finally, Portugal, already having a long, but essentially abandoned colonial Empire in the area through the mostly defunct proxy state Kongo Empire, also claimed the area due to old treaties with its old proxy, the Kingdom of Spain, and the Roman Catholic Church. It quickly made a treaty with its old ally, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 26 February 1884 to block off the Congo Society’s access to the Atlantic.

As a result of these diplomatic maneuvers and the subsequent colonial exploration expedition, by the early 1880s due to Africa’s abundance of valuable resources such as gold, timber, land, markets and labour power. European interest in Africa increased dramatically. Henry Morton Stanley’s charting of the Congo River Basin (1874–1877) removed the last bit of terra incognita from European maps of the continent thereby delineating the rough areas of British, Portuguese, French, and Belgium control. The remaining race was therefore left to pushing these rough boundaries to their furthest limits and eliminating any potential local minor powers which might prove troublesome through other European competitive diplomacy.

Thus, France moved to occupy Tunisia, one of the last of the Barbary Pirate states under the pretext of another Islamic terror and piracy incident. French claims by Peirre de Brazza, were quickly solidified with French taking control of today’s Republic of the Congo in 1881 and also Guinea in 1884. This in turn, partly convinced Italy to become part of the Triple Alliance, thereby

upsetting the German Chancellor

Otto Von Bismark’s carefully laid plans with Italy and forcing Germany to become involved. Germany began its world expansion in the 1880s under Bismarck’s leadership, encouraged by the national

bourgeoisie. Germany thus became the third largest colonial power in Africa, acquiring an overall empire of 2.6 million square kilometres and 14 million colonial subjects, mostly in its African possessions (Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika).

In 1882, realizing the geopolitical extent of Portuguese control on the coasts, but seeing penetration by France eastward across Central Africa toward Ethiopia, the Nile, and the Suez Canal, Britain saw its vital trade route through Egypt and its Indian Empire threatened. Thus, under the pretext of the collapsed Egyptian financing and a subsequent riot which killed hundreds of Europeans and British subjects murdered or injured, the United Kingdom intervened in nominally Ottoman Egypt, which in turn ruled over the Sudan and what would later become British Somaliland.

Within just 20 years the political face of Africa had changed – with only Liberia (a colony run by ex- African-American slaves) and Ethiopia remaining free of European control. The start of the 1880s saw a rapid increase in European nations claiming territory in Africa:

In 1880 the region to the north of the river Congo became a

French protectorate following a treaty between the

King of the Bateke, Makoko, and the explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.

In 1881 Tunisia became a French protectorate and the Transvaal regained its independence.

In 1882 Britain occupied Egypt (France pulled out of joint occupation), Italy begins colonization of Eritrea.

In 1884 British and French Somaliland created.

In 1884 German South West Africa, Cameroon, German East Africa, and Togo created, Río de Oro claimed by Spain.

Europeans Set the Rules for Dividing Up the Continent

The scramble for Africa led Bismarck to propose the 1884-85Berlin Conference. The Conference (and the resultant General Act of the Conference at Berlin) laid down ground rules for the further partitioning of Africa. Navigation on the Niger and Congo rivers was to be free to all, and to declare a protectorate over a region the European colonizer must show effective occupancy and develop a ‘sphere of influence’. The floodgates of European colonization had opened.

The Berlin Conference (German: Kongokonferenz or “Congo Conference”) of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany’s sudden emergence as an imperial power. Called for by Portugal and organized by Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, can be seen as the formalization of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity by European powers, while simultaneously eliminating most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance.

Owing to the upsetting of Bismark’s carefully laid balance of power in European politics caused by Leopold’s gamble and subsequent European race for colonies, Germany felt compelled to act and started launching expeditions of its own which both frightened British and French statesmen. Hoping to quickly smother this brewing conflict, King Leopold II was able to convince France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. Under support from the British and the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway (union until 1905), the Ottoman Empire, and the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference to work out policy. However, the United States did not actually participate in the conference both because it had an inability to take part in territorial expeditions as well as a sense of not giving the conference further legitimacy

The General Act fixed the following points:

To gain public acceptance a primary point of the conference was the ending of slavery by Black and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members.

The Free State of the Congo was confirmed as private property of the Congo Society thereby ensuring that Leopold’s promises to keep the country open to all European investment was retained. Thus the territory of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, some two million square kilometers, was made essentially the property of Léopold II, but later would eventually become a Belgian colony).

The 14 signatory powers would have free trade throughout the Congo basin as well as Lake Niassa and east of this in an area south of 5° N. The Niger and Congo Rivers were made free for ship traffic.

A Principle of Effectively (see below) was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.The Principle of Effectively stated that powers could hold colonies only if they actually possessed them: in other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their lag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order. The colonial power also had to make use of the colony economically. If the colonial power did not do these things, another power could do so and take over the territory. It therefore became important to get leaders to sign a protectorate treaty and to have a presence sufficient to police the area.

Great Britain desired a Cape-to-Cairo collection of colonies and almost succeeded though their control of Egypt, Sudan (Anglo-Egyptian Sudan), Uganda, Kenya (British East Africa), South Africa, and Zambia, Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), and Botswana. The British also controlled Nigeria and Ghana (Gold Coast).

France took much of western Africa, from Mauritania to Chad (French West Africa) and Gabon and the Republic of Congo (French Equatorial Africa).

Belgium and King Leopold II controlled the Democratic Republic of Congo (Belgian Congo).

Portugal took Mozambique in the east and Angola in the west.

Italy’s holdings were Somalia (Italian Somaliland) and a portion of Ethiopia.

Germany took Namibia (German Southwest Africa) and Tanzania (German East Africa).

Spain claimed the smallest territory – Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni).

Following the 1904

Entente cordiale between France and the UK, Germany tried to test the alliance in 1905, with the First Moroccan Crisis. This led to the 1905 Algeciras Conference, in which France’s influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of others territories, and then to the 1911 Agadir Crisis. Along with the 1898

Fashoda Incident between France and the UK, this succession of international crisis proves the bitterness of the struggle between the various imperial

powers, which ultimately led to World War I.

Italy continued its conquest to gain its “place in the sun”. Following the defeat of the First Italo-Abyssinian War (1895-96), it acquired Somaliland in 1899-90 and the whole of Eritrea (1899). In 1911, it engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya).

Enrico Corradini, who fully supported the war, and later merged

his group the early fascist party (PNF), developed in 1919 the concept of

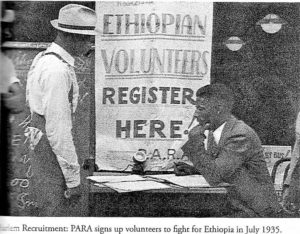

Proletarian Nationalism, supposed to legitimize Italy’s imperialism by a surprising mixture of socialism with nationalism: “We must start by recognizing the fact that there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes; that is to say, there are nations whose living conditions are subject…to the way of life of other nations, just as classes are. Once this is realized, nationalism must insist firmly on this truth: Italy is, materially and morally, a proletarian nation.” The Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935-36), ordered by Mussolini, would actually be one of the last colonial wars (that is, intended to colonize a foreign country, opposed to wars of national liberation), occupying Ethiopia for 5 years, which had remained the last African independent territory.

Even the United States took part, marginally, in this enterprise, through the American Colonization Society (ACS), established in 1816 by Robert Finley. The ACS offered emigration to Liberia (“Land of the Free”), a colony founded in 1820, to free black slaves; emancipated slave Lott Cary actually became the first American Baptist missionary in Africa. This colonization attempt was resisted by the native people.

Led by Southerners, the American Colonization Society’s first president was James Monroe, from Virginia, who became the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. Thus, one of the main proponents of American colonization of Africa was the same man who proclaimed, in his 1823 State of the Union address, the US opinion that European powers should no longer colonize the Americas or interfere with the affairs of sovereign nations located in the Americas. In return, the US planned to stay neutral in wars between European powers and in wars between a European power and its colonies. However, if these latter type of wars were to occur in the Americas, the U.S. would view such action as hostile toward itself. This famous statement became known as the Monroe Doctrine and was the base of the US’ isolationism during the 19th century.

Although the Liberia colony never became quite as big as envisaged, it was only the first step in the American colonization of Africa, according to its early proponents. Thus, J

ehudi Ashmun, an early leader of the ACS, envisioned an American empire in Africa.

Between 1825 and 1826, he took steps to lease, annex, or buy tribal lands along the coast and along major rivers leading inland. Like his predecessor Lt. Robert Stockton, who in 1821 established the site for Monrovia by “persuading” a local chief referred to as “King Peter” to sell Cape Montserado (or Mesurado) by pointing a pistol at his head, Ashmun was prepared to use force to extend the colony’s territory. In a May 1825 treaty, King Peter and other native kings agreed to sell land in return for 500 bars of tobacco, three barrels of rum, five casks of powder, five umbrellas, ten iron posts, and ten pairs of shoes, among other items. In March 1825, the ACS began a quarterly,

The African Repository and Colonial Journal, edited by Rev. Ralph Randolph Gurley (1797-1872), who headed the Society until 1844. Conceived as the Society’s propaganda organ, the Repository promoted both colonization and Liberia.

The Society controlled the colony of Liberia until 1847 when, under the perception that the British might annex the settlement, Liberia was proclaimed a free and independent state, thus becoming the first African decolonised state. By 1867, the Society had sent more than 13,000 emigrants. After the American Civil War (1861-1865), when many blacks wanted to go to Liberia, financial support for colonization had waned. During its later years the society focused on educational and missionary efforts in Liberia rather than further emigration. President Abraham Lincoln was rumored to have repeatedly tried to arrange resettlements of the kind the ACS supported, but each arrangement failed. According to those rumors, by 1865 Lincoln was one of the few strong advocates of colonization remaining in the United States Government, causing the program’s abandonment after his assassination.

Build up to the First World War

Britain’s occupations of Egypt and the Cape Colony contributed to a preoccupation over securing the source of the Nile River. Egypt was occupied by British forces in 1882 (although not formally declared a protectorate until 1914, and never a colony proper); Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda were subjugated in the 1890s and early 1900s; and in the south, the Cape Colony (first acquired in 1795) provided a base for the subjugation of neighbouring African states and the Dutch Afrikaner settlers who had left the Cape to avoid the British and then founded their own republics.

In 1877,

Theophilus Shepstone annexed the South African

Republic (or Transvaal — independent from 1857 to 1877) for the British. The UK consolidated its power over most of the colonies of South Africa in 1879 after the Anglo-Zulu War. The Boers protested and in December 1880 they revolted, leading to the First Boer War (1880-1881). The head of the British government Gladstone (Liberal) signed a peace treaty on March 23, 1881, giving self-government to the Boers in the Transvaal. The Second Boer War was fought between1899 to 1902; the independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and of the South African Republic (Transvaal) were this time defeated and absorbed into the British Empire.

The 1898 Fashoda Incident

The 1898

Fashoda Incident was one of the most crucial conflicts on Europe’s way to consolidating holdings in the continent. It brought Britain and France to the verge of war but ended in a major strategic victory for Britain, and provided the basis for the 1904

Entente Cordiale between the two rival countries. It stemmed from battles over control of the Nile headwaters, which caused Britain to expand in the Sudan.

The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from West Africa (modern day Senegal) eastward, through the Sahel along the southern border of the Sahara, a territory covering modern day Senegal, Mali, Niger, and Chad. Their ultimate aim was to have an uninterrupted link between the Niger River and the Nile, thus controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region, by virtue of their existing control over the Caravan routes through the Sahara.

The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in Southern Africa (modern South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Zambia), with their territories in East Africa (modern Kenya), and these two areas with the Nile basin. Sudan (which in those days included modern day Uganda) was obviously key to the fulfilment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt was already under British control.

This ‘red line’ through Africa is made most famous by Cecil Rhodes. Along with

Lord Milner (the British colonial minister in South Africa), Rhodes advocated such a “Cape to Cairo” empire linking by rail the Suez Canal to the mineral-rich Southern part of the continent.

Though hampered by German occupation of Tanganyika until the end of World War I, Rhodes successfully lobbied on behalf of such a sprawling East African empire. If one draws a line from Cape Town to Cairo (Rhodes’ dream), and one from Dakar to the Horn of Africa (now Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia), (the French ambition), these two lines intersect somewhere in eastern Sudan near Fashoda, explaining its strategic importance. In short, Britain had sought to extend its East African empire contiguously from Cairo to the Cape of Good Hope, while France had sought to extend its own holdings from Dakar to the Sudan, which would enable its empire to span the entire continent from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

A French force under

Jean-Baptiste Marchand arrived first at the

strategically located fort at Fashoda soon followed by a British force under Lord Kitchener, commander in chief of the British army since 1892. The French withdrew after a standoff, and continued to press claims to other posts in the region. In March 1899 the French and British agreed that the source of the Nile and Congo Rivers should mark the frontier between their spheres of influence.

Although the 1884-85 Berlin Conference had set the rules for the scramble for Africa, it hadn’t weakened the rival imperialisms. The 1898 Fachoda Incident, which had seen France and the UK on the brink of war, ultimately led to the signature of the 1904

Entente cordiale, which reversed the influence of the various European powers. As a result, the new German power decided to test the solidity of the influence, using the contested territory of Morocco as a battlefield.

Thus, on March 31, 1905, the

Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Tangiers

and made a speech in favour of Moroccan independence, challenging French influence in Morocco. France’s influence in Morocco had been reaffirmed by Britain and Spain in 1904. The Kaiser’s speech bolstered French nationalism and with British support the French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé, took a defiant line. The crisis peaked in mid-June 1905, when Delcassé was forced out of the ministry by the more conciliation minded Premier Maurice Rouvier. But by July 1905 Germany was becoming isolated and the French agreed to a conference to solve the crisis. Both France and Germany continued to posture up to the conference, with Germany mobilizing reserve army units in late December and France actually moving troops to the border in January 1906.

The 1906 Algeciras Conference was called to settle the dispute. Of the thirteen nations present the German representatives found their only supporter was Austria-Hungary. France had firm support from Britain, Russia, Italy, Spain, and the U.S. The Germans eventually accepted an agreement, signed on May 31, 1906, where France yielded certain domestic changes in Morocco but retained control of key areas.

However, five years later, the second Moroccan crisis (or Agadir Crisis) was sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat

Panther, to the port of Agadir on July 1, 1911. Germany had started to attempt to surpass Britain’s naval supremacy — the British navy had a policy of remaining larger than the next two naval fleets in the world combined. When the British heard of the

Panther’s arrival in Morocco, they wrongly believed that the Germans meant to turn Agadir into a naval base on the Atlantic.

The German move was aimed at reinforcing claims for compensation for acceptance of effective French control of the North African kingdom, where France’s pre-eminence had been upheld by the 1906 Algerisas Conference. In November 1911, a convention was signed under which Germany accepted France’s position in Morocco in return for territory in the French Equatorial African colony of Middle Congo (now the Republic of the Congo).

France subsequently established a full protectorate over Morocco (March 30, 1912), ending what remained of the country’s formal independence. Furthermore, British backing for France during the two Moroccan crises reinforced the Entente between the two countries and added to Anglo-German estrangement, deepening the divisions which would culminate in World War I.

Conclusions

During the New Imperialism period, by the end of the century, Europe added almost 9 million square miles (23,000,000 km²) — one-fifth of the land area of the globe — to its overseas colonial possessions. Europe’s formal holdings now included the entire African continent except Ethiopia, Liberia, and Saguia el-Hamra, the latter of which would be integrated into Spanish Sahara. Between 1885 and 1914 Britain took nearly 30% of Africa’s population under its control, to 15% for France, 9% for Germany, 7% for Belgium and only 1% for Italy. Nigeria alone contributed 15 million subjects, more than in the whole of French West Africa or the entire German colonial empire. It was paradoxical that Britain, the staunch advocate of free trade, emerged in 1914 with not only the largest overseas empire thanks to its long-standing presence in India, but also the greatest gains in the “scramble for Africa”, reflecting its advantageous position at its inception. In terms of surface area occupied, the French were the marginal victors but most of their empire was covered by desert.

The political imperialism followed the economic expansion, with the “colonial lobbies” bolstering chauvinism and jingoism at each crisis in order to legitimize the colonial enterprise. The tensions between the imperial powers led to a succession of crisis, which finally exploded in August 1914, when previous rivalries and alliances created a domino situation that drew the major European nations into the war. Austria-Hungary attacked Serbia to avenge

the murder by Serbian agents of

Austrian crown prince Francis Ferdinand, Russia would mobilize to assist its slav brothers in Serbia, Germany would intervene to support Austria-Hungary against Russia. Since Russia had a military alliance with France against Germany, the German General Staff, led by General von Moltke decided to realize the well prepared Schlieffen Plan to invade France and quickly knock her out of the war before turning against Russia in what was expected to be a long campaign. This required an invasion of Belgium which brought Great Britain into the war against Germany, Austria-Hungary and their allies. German U-Boat campaigns against ships bound for Britain eventually drew the United States into what had become the First World War. Moreover, using the Anglo-Japanese Alliance as an excuse, Japan leaped onto this opportunity to conquer German interests in China and the Pacific to become the dominating power in Western Pacific, setting the stage for the Second Sino-Japanese War (starting in 1937) and eventually the Second World War.

The Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated

The Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated

[/emember_protected]

]]>

of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period. But it wouldn’t have happened except for the particular economic, social, and military evolution Europe was going through.

As a result of the heightened tension between European states in the last quarter of the 19th century, the partitioning of Africa may be seen as a way for the Europeans to eliminate the threat of a Europe-wide war over Africa. The latter half of the 19th century saw the transition from the “informal” imperialism of control through military influence and economic dominance to that of direct rule. Attempts to mediate imperial competition, such as the Berlin Conference (1884 – 1885) among the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the French Third Republic and the German Empire, failed to establish definitively the competing powers’ claims. Dispute over Africa was one of the factors leading to the First World War.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The opening of Africa to Western exploration and exploitation had begun in earnest at the end of the 18th century. By 1835, Europeans had mapped most of north-western Africa. Among the most famous of the European explorers was David Livingstone,

of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period. But it wouldn’t have happened except for the particular economic, social, and military evolution Europe was going through.

As a result of the heightened tension between European states in the last quarter of the 19th century, the partitioning of Africa may be seen as a way for the Europeans to eliminate the threat of a Europe-wide war over Africa. The latter half of the 19th century saw the transition from the “informal” imperialism of control through military influence and economic dominance to that of direct rule. Attempts to mediate imperial competition, such as the Berlin Conference (1884 – 1885) among the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the French Third Republic and the German Empire, failed to establish definitively the competing powers’ claims. Dispute over Africa was one of the factors leading to the First World War.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

United Kingdom and the British Empire

The opening of Africa to Western exploration and exploitation had begun in earnest at the end of the 18th century. By 1835, Europeans had mapped most of north-western Africa. Among the most famous of the European explorers was David Livingstone,  who charted the vast interior and Serpa Pinto, who crossed both Southern Africa and Central Africa on a difficult expedition, mapping much of the interior of the continent. Arduous expeditions in the 1850s and 1860s by Richard Burton, John Speke and James Grant located the great central lakes and the source of the Nile. By the end of the century, Europeans had charted the Nile from its source, the courses of the Niger, Congo and Zambezi Rivers had been traced, and the world now realized the vast resources of Africa.

However, on the eve of the New Imperialist scramble for Africa, only ten per cent of the continent was under the control of Western nations. In 1875, the most important holdings were Algeria, whose conquest by France had started in the 1830s — despite Abd al-Qadir’s strong resistance and the Kabyles’ rebellion in the 1870s; the Cape Colony, held by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; and Angola, held by Portugal.

Leading Factors

There were several factors which created the impetus for the Scramble for Africa; most of these were to do with events in Europe rather than in Africa.

End of the Slave Trade .

Britain had had some success in halting the slave trade around the shores of Africa. But inland the story was different. Muslim traders from north of the Sahara and on the East Coast still traded inland, and many local chiefs were reluctant to give up the use of slaves. Reports of slaving trips and markets were brought back to Europe by various explorers, such as Livingstone, and abolitionists in Britain and Europe were calling for more to be done.

Exploration.

During the nineteenth century barely a year went by without a European expedition into Africa. The boom in exploration was triggered to a great extent by the creation of the African Association by wealthy Englishmen in 1788 (who wanted someone to ‘find’ the fabled city of Timbuktu and the course of the Niger River). As the century moved on, the goal of the European explorer changed, and rather than traveling out of pure curiosity they started to record details of markets, goods, and resources for the wealthy philanthropists who financed their trips.

Henry Morton Stanley.

who charted the vast interior and Serpa Pinto, who crossed both Southern Africa and Central Africa on a difficult expedition, mapping much of the interior of the continent. Arduous expeditions in the 1850s and 1860s by Richard Burton, John Speke and James Grant located the great central lakes and the source of the Nile. By the end of the century, Europeans had charted the Nile from its source, the courses of the Niger, Congo and Zambezi Rivers had been traced, and the world now realized the vast resources of Africa.

However, on the eve of the New Imperialist scramble for Africa, only ten per cent of the continent was under the control of Western nations. In 1875, the most important holdings were Algeria, whose conquest by France had started in the 1830s — despite Abd al-Qadir’s strong resistance and the Kabyles’ rebellion in the 1870s; the Cape Colony, held by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; and Angola, held by Portugal.

Leading Factors

There were several factors which created the impetus for the Scramble for Africa; most of these were to do with events in Europe rather than in Africa.

End of the Slave Trade .

Britain had had some success in halting the slave trade around the shores of Africa. But inland the story was different. Muslim traders from north of the Sahara and on the East Coast still traded inland, and many local chiefs were reluctant to give up the use of slaves. Reports of slaving trips and markets were brought back to Europe by various explorers, such as Livingstone, and abolitionists in Britain and Europe were calling for more to be done.

Exploration.

During the nineteenth century barely a year went by without a European expedition into Africa. The boom in exploration was triggered to a great extent by the creation of the African Association by wealthy Englishmen in 1788 (who wanted someone to ‘find’ the fabled city of Timbuktu and the course of the Niger River). As the century moved on, the goal of the European explorer changed, and rather than traveling out of pure curiosity they started to record details of markets, goods, and resources for the wealthy philanthropists who financed their trips.

Henry Morton Stanley.

A naturalized American (born in Wales) who of all the explorers of Africa is the one most closely connected to the start of the Scramble for Africa. Stanley had crossed the continent and located the ‘missing’ Livingstone, but he is more infamously known for his explorations on behalf of King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold hired Stanley to obtain treaties with local chieftains along the course of the River Congo with an eye to creating his own colony (Belgium was not in a financial position to fund a colony at that time). Stanley’s work triggered a rush of European explorers, such as Carl Peters, to do the same for various European countries.

Capitalism

The end of European trading in slaves left a need for commerce between Europe and Africa. Capitalists may have seen the light over slavery, but they still wanted to exploit the continent new ‘legitimate’ trade would be encouraged. Explorers located vast reserves of raw materials; they plotted the course of trade routes, navigated rivers, and identified population centers which could be a market for manufactured goods from Europe. It was a time of plantations and cash crops, dedicating the region’s workforce to producing rubber, coffee, sugar, palm oil, timber, etc. for Europe. And all the more enticing if a colony could be set up which gave the European nation a monopoly.

Steam Engines and Iron Hulled Boats.

A naturalized American (born in Wales) who of all the explorers of Africa is the one most closely connected to the start of the Scramble for Africa. Stanley had crossed the continent and located the ‘missing’ Livingstone, but he is more infamously known for his explorations on behalf of King Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold hired Stanley to obtain treaties with local chieftains along the course of the River Congo with an eye to creating his own colony (Belgium was not in a financial position to fund a colony at that time). Stanley’s work triggered a rush of European explorers, such as Carl Peters, to do the same for various European countries.

Capitalism

The end of European trading in slaves left a need for commerce between Europe and Africa. Capitalists may have seen the light over slavery, but they still wanted to exploit the continent new ‘legitimate’ trade would be encouraged. Explorers located vast reserves of raw materials; they plotted the course of trade routes, navigated rivers, and identified population centers which could be a market for manufactured goods from Europe. It was a time of plantations and cash crops, dedicating the region’s workforce to producing rubber, coffee, sugar, palm oil, timber, etc. for Europe. And all the more enticing if a colony could be set up which gave the European nation a monopoly.

Steam Engines and Iron Hulled Boats.

In 1840 the Nemesis arrived at Macao, south China. It changed the face of international relations between Europe and the rest of the world. The Nemesis had a shallow draft (five feet), a hull of iron, and two powerful steam engines. It could navigate the non-tidal sections of rivers, allowing access inland, and it was heavily armed. Livingstone used a steamer to travel up the Zambezi in 1858, and had the parts transported overland to Lake Nyassa. Steamers also allowed Henry Morton Stanley and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza to explore the Congo.

Medical Advances

Africa, especially the western regions, was known as the ‘White Man’s Grave’ because of the danger of two diseases: malaria and yellow fever. During the eighteenth century only one in ten Europeans sent out to the continent by the Royal African Company survived. Six of the ten would have died in their first year. In 1817 two French scientists, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, extracted quinine from the bark of the South American cinchona tree. It proved to be the solution to malaria; Europeans could now survive the ravages of the disease in Africa. (Unfortunately yellow fever continued to be a problem – and even today there is no specific treatment for the disease.)

Politics

After the creation of a unified Germany (1871) and Italy (a longer process, but its capital relocated to Rome also in 1871) there was no room left in Europe for expansion. Britain, France and Germany were in an intricate political dance, trying to maintain their dominance, and an empire would secure it. France, which had lost two provinces to Germany in 1870, looked to Africa to gain more territory. Britain looked towards Egypt and the control of the Suez Canal as well as pursuing territory in gold rich southern Africa. Germany, under the expert management of Chancellor Bismarck, had come late to the idea of overseas colonies, but was now fully convinced of their worth. (It would need some mechanism to be put in place to stop overt conflict over the coming land grab.)

Military Innovation

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Europe was only marginally ahead of Africa in terms of available weapons as traders had long supplied them to local chiefs and many had stockpiles of guns and gunpowder. But two innovations gave Europe a massive advantage. In the late 1860s percussion caps were being incorporated into cartridges what previously came as a separate bullet, powder and wadding, was now a single entity, easily transported and relatively weather proof. The second innovation was the breach loading rifle. Older model muskets, held by most Africans, were front loaders, slow to use (maximum of three rounds per minute) and had to be loaded whilst standing. Breach loading guns, in comparison, had between two to four times the rates of fire, and could be loaded even in a prone position. Europeans, with an eye to colonization and conquest, restricted the sale of the new weaponry to Africa maintaining military superiority.

Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by “informal imperialism” and “civilization”, was also attractive to Europe’s ruling elites for economic and racial reasons. During a time when Britain’s balance of trade showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets due to the Long Depression (1873-1896), Africa offered Britain, Germany and other countries an open market that would garner it a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the metropolis than it sold overall. Britain, like most other industrial countries, had long since begun to run an unfavorable balance of trade (which was increasingly offset, however, by the income from overseas investments)

As Britain developed into the world’s first post-industrial nation, financial services became an increasingly important sector of its economy. Invisible financial exports, as mentioned, kept Britain out of the red, especially capital investments outside Europe, particularly to the developing and open markets in Africa, predominantly white settler colonies, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

In addition, surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap labor, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement to imperialism, of course, arose from the demand for raw materials unavailable in Europe, especially copper, cotton, rubber, tea, and tin, to which European consumers had grown accustomed and upon which European industry had grown dependent.

In 1840 the Nemesis arrived at Macao, south China. It changed the face of international relations between Europe and the rest of the world. The Nemesis had a shallow draft (five feet), a hull of iron, and two powerful steam engines. It could navigate the non-tidal sections of rivers, allowing access inland, and it was heavily armed. Livingstone used a steamer to travel up the Zambezi in 1858, and had the parts transported overland to Lake Nyassa. Steamers also allowed Henry Morton Stanley and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza to explore the Congo.

Medical Advances

Africa, especially the western regions, was known as the ‘White Man’s Grave’ because of the danger of two diseases: malaria and yellow fever. During the eighteenth century only one in ten Europeans sent out to the continent by the Royal African Company survived. Six of the ten would have died in their first year. In 1817 two French scientists, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, extracted quinine from the bark of the South American cinchona tree. It proved to be the solution to malaria; Europeans could now survive the ravages of the disease in Africa. (Unfortunately yellow fever continued to be a problem – and even today there is no specific treatment for the disease.)

Politics

After the creation of a unified Germany (1871) and Italy (a longer process, but its capital relocated to Rome also in 1871) there was no room left in Europe for expansion. Britain, France and Germany were in an intricate political dance, trying to maintain their dominance, and an empire would secure it. France, which had lost two provinces to Germany in 1870, looked to Africa to gain more territory. Britain looked towards Egypt and the control of the Suez Canal as well as pursuing territory in gold rich southern Africa. Germany, under the expert management of Chancellor Bismarck, had come late to the idea of overseas colonies, but was now fully convinced of their worth. (It would need some mechanism to be put in place to stop overt conflict over the coming land grab.)

Military Innovation

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Europe was only marginally ahead of Africa in terms of available weapons as traders had long supplied them to local chiefs and many had stockpiles of guns and gunpowder. But two innovations gave Europe a massive advantage. In the late 1860s percussion caps were being incorporated into cartridges what previously came as a separate bullet, powder and wadding, was now a single entity, easily transported and relatively weather proof. The second innovation was the breach loading rifle. Older model muskets, held by most Africans, were front loaders, slow to use (maximum of three rounds per minute) and had to be loaded whilst standing. Breach loading guns, in comparison, had between two to four times the rates of fire, and could be loaded even in a prone position. Europeans, with an eye to colonization and conquest, restricted the sale of the new weaponry to Africa maintaining military superiority.

Sub-Saharan Africa, one of the last regions of the world largely untouched by “informal imperialism” and “civilization”, was also attractive to Europe’s ruling elites for economic and racial reasons. During a time when Britain’s balance of trade showed a growing deficit, with shrinking and increasingly protectionist continental markets due to the Long Depression (1873-1896), Africa offered Britain, Germany and other countries an open market that would garner it a trade surplus: a market that bought more from the metropolis than it sold overall. Britain, like most other industrial countries, had long since begun to run an unfavorable balance of trade (which was increasingly offset, however, by the income from overseas investments)

As Britain developed into the world’s first post-industrial nation, financial services became an increasingly important sector of its economy. Invisible financial exports, as mentioned, kept Britain out of the red, especially capital investments outside Europe, particularly to the developing and open markets in Africa, predominantly white settler colonies, the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

In addition, surplus capital was often more profitably invested overseas, where cheap labor, limited competition, and abundant raw materials made a greater premium possible. Another inducement to imperialism, of course, arose from the demand for raw materials unavailable in Europe, especially copper, cotton, rubber, tea, and tin, to which European consumers had grown accustomed and upon which European industry had grown dependent.

However, in Africa — exclusive of what would become the Union of South Africa in 1909 — the amount of capital investment by Europeans was relatively small, compared to other continents, before and after the 1884-85 Berlin Conference. Consequently, the companies involved in tropical African commerce were relatively small, apart from Cecil Rhodes’ De Beers Mining Company, who had carved out Rhodesia for himself, as Léopold II would exploit the Congo Free State.

The Mad Rush Into Africa in the Early 1880s

Africa was treated in diplomacy at the time in the same manner as the New World Indians. Thus, by the middle 1800s, the Continent was considered disputed territory ripe for exploration, trade, and settlement. However, the continent except for the traditional posts along the coasts was essentially ignored. But, this state changed as a result of King Leopold of Belgium’s desire for glory.

In 1878, King Léopold II of Belgium who had previously founded the International African Society in 1876 invited Stanley to join him in researching and ‘civilizing’ the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society was also formed, with more economic goals, but still closely related to the former society. Léopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic goals, with the African Society serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

Thus, from 1879 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo, this time not as a reporter, but as an envoy from Léopold with the secret mission to organize what would become known as the Congo Free State. In the meantime, French intelligence had discovered Leopold’s plans and was quickly engaging in its own

However, in Africa — exclusive of what would become the Union of South Africa in 1909 — the amount of capital investment by Europeans was relatively small, compared to other continents, before and after the 1884-85 Berlin Conference. Consequently, the companies involved in tropical African commerce were relatively small, apart from Cecil Rhodes’ De Beers Mining Company, who had carved out Rhodesia for himself, as Léopold II would exploit the Congo Free State.

The Mad Rush Into Africa in the Early 1880s

Africa was treated in diplomacy at the time in the same manner as the New World Indians. Thus, by the middle 1800s, the Continent was considered disputed territory ripe for exploration, trade, and settlement. However, the continent except for the traditional posts along the coasts was essentially ignored. But, this state changed as a result of King Leopold of Belgium’s desire for glory.

In 1878, King Léopold II of Belgium who had previously founded the International African Society in 1876 invited Stanley to join him in researching and ‘civilizing’ the continent. In 1878, the International Congo Society was also formed, with more economic goals, but still closely related to the former society. Léopold secretly bought off the foreign investors in the Congo Society, which was turned to imperialistic goals, with the African Society serving primarily as a philanthropic front.

Thus, from 1879 to 1885, Stanley returned to the Congo, this time not as a reporter, but as an envoy from Léopold with the secret mission to organize what would become known as the Congo Free State. In the meantime, French intelligence had discovered Leopold’s plans and was quickly engaging in its own  colonial exploration. French naval officer Pierre de Brazza was dispatched to central Africa, traveled into the western Congo basin and raised the French flag over the newly-founded Brazzaville in 1881, in what is currently the Republic of Congo. Finally, Portugal, already having a long, but essentially abandoned colonial Empire in the area through the mostly defunct proxy state Kongo Empire, also claimed the area due to old treaties with its old proxy, the Kingdom of Spain, and the Roman Catholic Church. It quickly made a treaty with its old ally, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 26 February 1884 to block off the Congo Society’s access to the Atlantic.

As a result of these diplomatic maneuvers and the subsequent colonial exploration expedition, by the early 1880s due to Africa’s abundance of valuable resources such as gold, timber, land, markets and labour power. European interest in Africa increased dramatically. Henry Morton Stanley’s charting of the Congo River Basin (1874–1877) removed the last bit of terra incognita from European maps of the continent thereby delineating the rough areas of British, Portuguese, French, and Belgium control. The remaining race was therefore left to pushing these rough boundaries to their furthest limits and eliminating any potential local minor powers which might prove troublesome through other European competitive diplomacy.

Thus, France moved to occupy Tunisia, one of the last of the Barbary Pirate states under the pretext of another Islamic terror and piracy incident. French claims by Peirre de Brazza, were quickly solidified with French taking control of today’s Republic of the Congo in 1881 and also Guinea in 1884. This in turn, partly convinced Italy to become part of the Triple Alliance, thereby

colonial exploration. French naval officer Pierre de Brazza was dispatched to central Africa, traveled into the western Congo basin and raised the French flag over the newly-founded Brazzaville in 1881, in what is currently the Republic of Congo. Finally, Portugal, already having a long, but essentially abandoned colonial Empire in the area through the mostly defunct proxy state Kongo Empire, also claimed the area due to old treaties with its old proxy, the Kingdom of Spain, and the Roman Catholic Church. It quickly made a treaty with its old ally, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 26 February 1884 to block off the Congo Society’s access to the Atlantic.

As a result of these diplomatic maneuvers and the subsequent colonial exploration expedition, by the early 1880s due to Africa’s abundance of valuable resources such as gold, timber, land, markets and labour power. European interest in Africa increased dramatically. Henry Morton Stanley’s charting of the Congo River Basin (1874–1877) removed the last bit of terra incognita from European maps of the continent thereby delineating the rough areas of British, Portuguese, French, and Belgium control. The remaining race was therefore left to pushing these rough boundaries to their furthest limits and eliminating any potential local minor powers which might prove troublesome through other European competitive diplomacy.

Thus, France moved to occupy Tunisia, one of the last of the Barbary Pirate states under the pretext of another Islamic terror and piracy incident. French claims by Peirre de Brazza, were quickly solidified with French taking control of today’s Republic of the Congo in 1881 and also Guinea in 1884. This in turn, partly convinced Italy to become part of the Triple Alliance, thereby  upsetting the German Chancellor Otto Von Bismark’s carefully laid plans with Italy and forcing Germany to become involved. Germany began its world expansion in the 1880s under Bismarck’s leadership, encouraged by the national bourgeoisie. Germany thus became the third largest colonial power in Africa, acquiring an overall empire of 2.6 million square kilometres and 14 million colonial subjects, mostly in its African possessions (Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika).

In 1882, realizing the geopolitical extent of Portuguese control on the coasts, but seeing penetration by France eastward across Central Africa toward Ethiopia, the Nile, and the Suez Canal, Britain saw its vital trade route through Egypt and its Indian Empire threatened. Thus, under the pretext of the collapsed Egyptian financing and a subsequent riot which killed hundreds of Europeans and British subjects murdered or injured, the United Kingdom intervened in nominally Ottoman Egypt, which in turn ruled over the Sudan and what would later become British Somaliland.

Within just 20 years the political face of Africa had changed – with only Liberia (a colony run by ex- African-American slaves) and Ethiopia remaining free of European control. The start of the 1880s saw a rapid increase in European nations claiming territory in Africa:

In 1880 the region to the north of the river Congo became a

upsetting the German Chancellor Otto Von Bismark’s carefully laid plans with Italy and forcing Germany to become involved. Germany began its world expansion in the 1880s under Bismarck’s leadership, encouraged by the national bourgeoisie. Germany thus became the third largest colonial power in Africa, acquiring an overall empire of 2.6 million square kilometres and 14 million colonial subjects, mostly in its African possessions (Southwest Africa, Togoland, the Cameroons, and Tanganyika).

In 1882, realizing the geopolitical extent of Portuguese control on the coasts, but seeing penetration by France eastward across Central Africa toward Ethiopia, the Nile, and the Suez Canal, Britain saw its vital trade route through Egypt and its Indian Empire threatened. Thus, under the pretext of the collapsed Egyptian financing and a subsequent riot which killed hundreds of Europeans and British subjects murdered or injured, the United Kingdom intervened in nominally Ottoman Egypt, which in turn ruled over the Sudan and what would later become British Somaliland.

Within just 20 years the political face of Africa had changed – with only Liberia (a colony run by ex- African-American slaves) and Ethiopia remaining free of European control. The start of the 1880s saw a rapid increase in European nations claiming territory in Africa:

In 1880 the region to the north of the river Congo became a  French protectorate following a treaty between the King of the Bateke, Makoko, and the explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.

In 1881 Tunisia became a French protectorate and the Transvaal regained its independence.

In 1882 Britain occupied Egypt (France pulled out of joint occupation), Italy begins colonization of Eritrea.

In 1884 British and French Somaliland created.

In 1884 German South West Africa, Cameroon, German East Africa, and Togo created, Río de Oro claimed by Spain.

Europeans Set the Rules for Dividing Up the Continent

The scramble for Africa led Bismarck to propose the 1884-85Berlin Conference. The Conference (and the resultant General Act of the Conference at Berlin) laid down ground rules for the further partitioning of Africa. Navigation on the Niger and Congo rivers was to be free to all, and to declare a protectorate over a region the European colonizer must show effective occupancy and develop a ‘sphere of influence’. The floodgates of European colonization had opened.

French protectorate following a treaty between the King of the Bateke, Makoko, and the explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.

In 1881 Tunisia became a French protectorate and the Transvaal regained its independence.

In 1882 Britain occupied Egypt (France pulled out of joint occupation), Italy begins colonization of Eritrea.

In 1884 British and French Somaliland created.

In 1884 German South West Africa, Cameroon, German East Africa, and Togo created, Río de Oro claimed by Spain.

Europeans Set the Rules for Dividing Up the Continent

The scramble for Africa led Bismarck to propose the 1884-85Berlin Conference. The Conference (and the resultant General Act of the Conference at Berlin) laid down ground rules for the further partitioning of Africa. Navigation on the Niger and Congo rivers was to be free to all, and to declare a protectorate over a region the European colonizer must show effective occupancy and develop a ‘sphere of influence’. The floodgates of European colonization had opened.

The Berlin Conference (German: Kongokonferenz or “Congo Conference”) of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany’s sudden emergence as an imperial power. Called for by Portugal and organized by Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, can be seen as the formalization of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity by European powers, while simultaneously eliminating most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance.

Owing to the upsetting of Bismark’s carefully laid balance of power in European politics caused by Leopold’s gamble and subsequent European race for colonies, Germany felt compelled to act and started launching expeditions of its own which both frightened British and French statesmen. Hoping to quickly smother this brewing conflict, King Leopold II was able to convince France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. Under support from the British and the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway (union until 1905), the Ottoman Empire, and the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference to work out policy. However, the United States did not actually participate in the conference both because it had an inability to take part in territorial expeditions as well as a sense of not giving the conference further legitimacy

The General Act fixed the following points:

The Berlin Conference (German: Kongokonferenz or “Congo Conference”) of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany’s sudden emergence as an imperial power. Called for by Portugal and organized by Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, its outcome, the General Act of the Berlin Conference, can be seen as the formalization of the Scramble for Africa. The conference ushered in a period of heightened colonial activity by European powers, while simultaneously eliminating most existing forms of African autonomy and self-governance.

Owing to the upsetting of Bismark’s carefully laid balance of power in European politics caused by Leopold’s gamble and subsequent European race for colonies, Germany felt compelled to act and started launching expeditions of its own which both frightened British and French statesmen. Hoping to quickly smother this brewing conflict, King Leopold II was able to convince France and Germany that common trade in Africa was in the best interests of all three countries. Under support from the British and the initiative of Portugal, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway (union until 1905), the Ottoman Empire, and the United States to take part in the Berlin Conference to work out policy. However, the United States did not actually participate in the conference both because it had an inability to take part in territorial expeditions as well as a sense of not giving the conference further legitimacy

The General Act fixed the following points:

To gain public acceptance a primary point of the conference was the ending of slavery by Black and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members.

The Free State of the Congo was confirmed as private property of the Congo Society thereby ensuring that Leopold’s promises to keep the country open to all European investment was retained. Thus the territory of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, some two million square kilometers, was made essentially the property of Léopold II, but later would eventually become a Belgian colony).

The 14 signatory powers would have free trade throughout the Congo basin as well as Lake Niassa and east of this in an area south of 5° N. The Niger and Congo Rivers were made free for ship traffic.

A Principle of Effectively (see below) was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.The Principle of Effectively stated that powers could hold colonies only if they actually possessed them: in other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their lag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order. The colonial power also had to make use of the colony economically. If the colonial power did not do these things, another power could do so and take over the territory. It therefore became important to get leaders to sign a protectorate treaty and to have a presence sufficient to police the area.

To gain public acceptance a primary point of the conference was the ending of slavery by Black and Islamic powers. Thus, an international prohibition of the slave trade throughout their respected spheres was signed by the European members.

The Free State of the Congo was confirmed as private property of the Congo Society thereby ensuring that Leopold’s promises to keep the country open to all European investment was retained. Thus the territory of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, some two million square kilometers, was made essentially the property of Léopold II, but later would eventually become a Belgian colony).

The 14 signatory powers would have free trade throughout the Congo basin as well as Lake Niassa and east of this in an area south of 5° N. The Niger and Congo Rivers were made free for ship traffic.

A Principle of Effectively (see below) was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.The Principle of Effectively stated that powers could hold colonies only if they actually possessed them: in other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their lag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force to keep order. The colonial power also had to make use of the colony economically. If the colonial power did not do these things, another power could do so and take over the territory. It therefore became important to get leaders to sign a protectorate treaty and to have a presence sufficient to police the area.

Great Britain desired a Cape-to-Cairo collection of colonies and almost succeeded though their control of Egypt, Sudan (Anglo-Egyptian Sudan), Uganda, Kenya (British East Africa), South Africa, and Zambia, Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), and Botswana. The British also controlled Nigeria and Ghana (Gold Coast).

France took much of western Africa, from Mauritania to Chad (French West Africa) and Gabon and the Republic of Congo (French Equatorial Africa).

Belgium and King Leopold II controlled the Democratic Republic of Congo (Belgian Congo).

Portugal took Mozambique in the east and Angola in the west.

Italy’s holdings were Somalia (Italian Somaliland) and a portion of Ethiopia.

Germany took Namibia (German Southwest Africa) and Tanzania (German East Africa).

Spain claimed the smallest territory – Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni).

Following the 1904 Entente cordiale between France and the UK, Germany tried to test the alliance in 1905, with the First Moroccan Crisis. This led to the 1905 Algeciras Conference, in which France’s influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of others territories, and then to the 1911 Agadir Crisis. Along with the 1898 Fashoda Incident between France and the UK, this succession of international crisis proves the bitterness of the struggle between the various imperial powers, which ultimately led to World War I.

Italy continued its conquest to gain its “place in the sun”. Following the defeat of the First Italo-Abyssinian War (1895-96), it acquired Somaliland in 1899-90 and the whole of Eritrea (1899). In 1911, it engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya).

Enrico Corradini, who fully supported the war, and later merged

Great Britain desired a Cape-to-Cairo collection of colonies and almost succeeded though their control of Egypt, Sudan (Anglo-Egyptian Sudan), Uganda, Kenya (British East Africa), South Africa, and Zambia, Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), and Botswana. The British also controlled Nigeria and Ghana (Gold Coast).

France took much of western Africa, from Mauritania to Chad (French West Africa) and Gabon and the Republic of Congo (French Equatorial Africa).

Belgium and King Leopold II controlled the Democratic Republic of Congo (Belgian Congo).

Portugal took Mozambique in the east and Angola in the west.

Italy’s holdings were Somalia (Italian Somaliland) and a portion of Ethiopia.

Germany took Namibia (German Southwest Africa) and Tanzania (German East Africa).

Spain claimed the smallest territory – Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni).

Following the 1904 Entente cordiale between France and the UK, Germany tried to test the alliance in 1905, with the First Moroccan Crisis. This led to the 1905 Algeciras Conference, in which France’s influence on Morocco was compensated by the exchange of others territories, and then to the 1911 Agadir Crisis. Along with the 1898 Fashoda Incident between France and the UK, this succession of international crisis proves the bitterness of the struggle between the various imperial powers, which ultimately led to World War I.

Italy continued its conquest to gain its “place in the sun”. Following the defeat of the First Italo-Abyssinian War (1895-96), it acquired Somaliland in 1899-90 and the whole of Eritrea (1899). In 1911, it engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, in which it acquired Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern Libya).

Enrico Corradini, who fully supported the war, and later merged  his group the early fascist party (PNF), developed in 1919 the concept of Proletarian Nationalism, supposed to legitimize Italy’s imperialism by a surprising mixture of socialism with nationalism: “We must start by recognizing the fact that there are proletarian nations as well as proletarian classes; that is to say, there are nations whose living conditions are subject…to the way of life of other nations, just as classes are. Once this is realized, nationalism must insist firmly on this truth: Italy is, materially and morally, a proletarian nation.” The Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935-36), ordered by Mussolini, would actually be one of the last colonial wars (that is, intended to colonize a foreign country, opposed to wars of national liberation), occupying Ethiopia for 5 years, which had remained the last African independent territory.

Even the United States took part, marginally, in this enterprise, through the American Colonization Society (ACS), established in 1816 by Robert Finley. The ACS offered emigration to Liberia (“Land of the Free”), a colony founded in 1820, to free black slaves; emancipated slave Lott Cary actually became the first American Baptist missionary in Africa. This colonization attempt was resisted by the native people.

Led by Southerners, the American Colonization Society’s first president was James Monroe, from Virginia, who became the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. Thus, one of the main proponents of American colonization of Africa was the same man who proclaimed, in his 1823 State of the Union address, the US opinion that European powers should no longer colonize the Americas or interfere with the affairs of sovereign nations located in the Americas. In return, the US planned to stay neutral in wars between European powers and in wars between a European power and its colonies. However, if these latter type of wars were to occur in the Americas, the U.S. would view such action as hostile toward itself. This famous statement became known as the Monroe Doctrine and was the base of the US’ isolationism during the 19th century.

Although the Liberia colony never became quite as big as envisaged, it was only the first step in the American colonization of Africa, according to its early proponents. Thus, Jehudi Ashmun, an early leader of the ACS, envisioned an American empire in Africa.