Life and Times of Haile Selassie I

Part 2

Italio-Ethiopian war

Ethiopia Prepares for War Ever since the crushing defeat of the Italian Army at Adowa in 1896, Italian officials, especially colonial officials had chaffed at the lack of revenge, or restoration of their honor Revenge for Adowa was considered essential for Italian prestige in Europe. Italian colonies in Libya, Italian (southern) Somali land and Eritrea were unprofitable, and in the case of Libya, unstable. The Italians increasingly saw Ethiopia as their natural hinterland for their Somali land and Eritrean colonies. A vast territory of industrious people, fertile soil, untapped mineral wealth and the prestige of ancient empire were a prize that they were simply unwilling to pass up for good.

The fact that relations between Ethiopia and Italy had been outwardly warm since the war of 1896 was no deterrent. As Crown Prince and Regent, the Emperor had visited Rome in 1923 and met with King Victor Emmanuel and Queen Helena, as well as Italy’s brand new Premier, a vulgar braggart and demagogue named Benito Mussolini. During the visit of Prince Regent Tafari, the leader of the Socialists in the Italian Parliament, and a vocal opponent to Mussolini’s fascism, mysteriously disappeared. A racist cartoon in a Rome Daily depicted the Ethiopian Prince asking el Deuce if he had eaten his opponent, as if that was typical behavior for Ethiopian leaders to eat their enemies.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

The Italian and Ethiopian governments renewed the treaty of Friendship and Commerce, and the King of Italy decorated the Prince with the Order of the Annunziata, entitling him to be called a “cousin” of the King of Italy. The Prince of Udine (later made king of the fascist puppet state in Croatia), an actual cousin of the King of Italy had even attended the Emperor’s coronation in 1930. At the same time, the new fascist government was laying down plans for the eventual conquest of the Ethiopian Empire. The excuse that Italy needed was provided by the

restoration of their honor Revenge for Adowa was considered essential for Italian prestige in Europe. Italian colonies in Libya, Italian (southern) Somali land and Eritrea were unprofitable, and in the case of Libya, unstable. The Italians increasingly saw Ethiopia as their natural hinterland for their Somali land and Eritrean colonies. A vast territory of industrious people, fertile soil, untapped mineral wealth and the prestige of ancient empire were a prize that they were simply unwilling to pass up for good.

The fact that relations between Ethiopia and Italy had been outwardly warm since the war of 1896 was no deterrent. As Crown Prince and Regent, the Emperor had visited Rome in 1923 and met with King Victor Emmanuel and Queen Helena, as well as Italy’s brand new Premier, a vulgar braggart and demagogue named Benito Mussolini. During the visit of Prince Regent Tafari, the leader of the Socialists in the Italian Parliament, and a vocal opponent to Mussolini’s fascism, mysteriously disappeared. A racist cartoon in a Rome Daily depicted the Ethiopian Prince asking el Deuce if he had eaten his opponent, as if that was typical behavior for Ethiopian leaders to eat their enemies.

To view the rest of this article please subscribe and update your membership by clicking this link, Subscribe Now !

[emember_protected member_id=”3″]

The Italian and Ethiopian governments renewed the treaty of Friendship and Commerce, and the King of Italy decorated the Prince with the Order of the Annunziata, entitling him to be called a “cousin” of the King of Italy. The Prince of Udine (later made king of the fascist puppet state in Croatia), an actual cousin of the King of Italy had even attended the Emperor’s coronation in 1930. At the same time, the new fascist government was laying down plans for the eventual conquest of the Ethiopian Empire. The excuse that Italy needed was provided by the  infamous Wal Wal incident and the un-demarcated border between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland.

Wal Wal was an outpost in the Ogaden desert that had wells used by the Somali nomads that freely crossed between British, French and Italian Somali lands, and the Ethiopian Ogaden. The treaty that set down the border between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia stated that the border ran parallel to the Benadir coast of Somalia at a distance of 21 leagues. What was unstated was if this meant 21 standard leagues or 21 nautical leagues. The Italians insisted on the nautical leagues, as this would push the border further inland, while the Ethiopians maintained it was absurd to claim that the treaty used nautical leagues to measure a distance on dry land.

Nevertheless, a contingent of Italian soldiers occupied the wells at Wal Wal and built a small fort on what Ethiopia claimed was clearly Ethiopian territory, and had been administered by the Ethiopians. Ethiopian territorial troops under the

infamous Wal Wal incident and the un-demarcated border between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland.

Wal Wal was an outpost in the Ogaden desert that had wells used by the Somali nomads that freely crossed between British, French and Italian Somali lands, and the Ethiopian Ogaden. The treaty that set down the border between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia stated that the border ran parallel to the Benadir coast of Somalia at a distance of 21 leagues. What was unstated was if this meant 21 standard leagues or 21 nautical leagues. The Italians insisted on the nautical leagues, as this would push the border further inland, while the Ethiopians maintained it was absurd to claim that the treaty used nautical leagues to measure a distance on dry land.

Nevertheless, a contingent of Italian soldiers occupied the wells at Wal Wal and built a small fort on what Ethiopia claimed was clearly Ethiopian territory, and had been administered by the Ethiopians. Ethiopian territorial troops under the  command of Fitawrarri Shiferaw (posthumously created a Dejazmatch) confronted the Italians, and after repeated requests for the Italians to leave the site, gunfire was exchanged. The fighting grew fierce and Italian airplanes bombed Ethiopian positions. Ethiopia complained to the League of Nations, calling on the collective security agreements embodied in the charter to be invoked and applied. The Italians railed that it was Ethiopia that had attacked an Italian fortification.

The Emperor assumed that the League would protect all members from aggression once the victim party was ascertained. In order to leave no doubt as to who was the aggressor, and in a move that showed exactly how much faith he had put in the League, the Emperor ordered all Ethiopian forces to withdraw from large areas along the borders with Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. In the meantime, Italy charged that its honour had been impinged. Ethiopia was depicted at the League as a savage and barbarous land where slavery and brutality were the common way of life, a land that did not deserve to be treated equally with “civilized countries”. Ethiopia was urged to find a way to accommodate the “civilizing influence” of Italy territorially in the Ogaden and even in Tigrai in the north.

The Ethiopian government refused all such urgings as impinging on its sovereignty. In November 1935, thousands of Italian troops accompanied by even more native colonial “Askari” troops crossed into Tigrai from Eritrea in the north under the command of Field Marshal De Bono, an elderly and cautious officer who

command of Fitawrarri Shiferaw (posthumously created a Dejazmatch) confronted the Italians, and after repeated requests for the Italians to leave the site, gunfire was exchanged. The fighting grew fierce and Italian airplanes bombed Ethiopian positions. Ethiopia complained to the League of Nations, calling on the collective security agreements embodied in the charter to be invoked and applied. The Italians railed that it was Ethiopia that had attacked an Italian fortification.

The Emperor assumed that the League would protect all members from aggression once the victim party was ascertained. In order to leave no doubt as to who was the aggressor, and in a move that showed exactly how much faith he had put in the League, the Emperor ordered all Ethiopian forces to withdraw from large areas along the borders with Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. In the meantime, Italy charged that its honour had been impinged. Ethiopia was depicted at the League as a savage and barbarous land where slavery and brutality were the common way of life, a land that did not deserve to be treated equally with “civilized countries”. Ethiopia was urged to find a way to accommodate the “civilizing influence” of Italy territorially in the Ogaden and even in Tigrai in the north.

The Ethiopian government refused all such urgings as impinging on its sovereignty. In November 1935, thousands of Italian troops accompanied by even more native colonial “Askari” troops crossed into Tigrai from Eritrea in the north under the command of Field Marshal De Bono, an elderly and cautious officer who  planned to progress slowly into the Empire. They were quickly followed by similar forces from Italian Somaliland in the south and east commanded by Marshal Graziani.

The fact that Italy had crossed deep into Ethiopian territory left little doubt as to whom the aggressor was, but there was still little will to stop the aggression. The Emperor had put complete faith in the League, and had resisted the calls of his nobles to declare war because he believed that the League would live up to the charter and rush in to protect his country. The Emperor’s logic was that the doctrine of “Collective Security” would obligate the League to protect Ethiopia.

An attack on one member of the League was supposed to be regarded as an attack on all the members. It was this protection that had inspired him to join the League in the first place back when he was still Prince-Regent and faced with hostile nobility which wanted no part of the “foreigners” League. However, at the time, Hitler was preparing to annex Austria, and the leading voice against this was Mussolini. Britain and France hoped to use Mussolini as a bulwark against German designs on Austria, and thus did not want alienate Mussolini over what they considered an unimportant African remnant.

Not only were they not going to help Ethiopia, but France went so far as to forbid the import of weapons into Ethiopia on the Addis Ababa – Djibouti railway. Instead they encouraged mild sanctions on Italy that did not include the all important petroleum used for military trucks and tanks. The sanctions were essentially

planned to progress slowly into the Empire. They were quickly followed by similar forces from Italian Somaliland in the south and east commanded by Marshal Graziani.

The fact that Italy had crossed deep into Ethiopian territory left little doubt as to whom the aggressor was, but there was still little will to stop the aggression. The Emperor had put complete faith in the League, and had resisted the calls of his nobles to declare war because he believed that the League would live up to the charter and rush in to protect his country. The Emperor’s logic was that the doctrine of “Collective Security” would obligate the League to protect Ethiopia.

An attack on one member of the League was supposed to be regarded as an attack on all the members. It was this protection that had inspired him to join the League in the first place back when he was still Prince-Regent and faced with hostile nobility which wanted no part of the “foreigners” League. However, at the time, Hitler was preparing to annex Austria, and the leading voice against this was Mussolini. Britain and France hoped to use Mussolini as a bulwark against German designs on Austria, and thus did not want alienate Mussolini over what they considered an unimportant African remnant.

Not only were they not going to help Ethiopia, but France went so far as to forbid the import of weapons into Ethiopia on the Addis Ababa – Djibouti railway. Instead they encouraged mild sanctions on Italy that did not include the all important petroleum used for military trucks and tanks. The sanctions were essentially  useless. The Foreign Ministers of France and Britain (Laval and Hoare) were secretly negotiating a solution that would involve Ethiopia handing over the Ogaden and most of Tigrai to the Italians, grant English hegemony over the basin of the Blue Nile, and the French control of the area adjacent to the railroad to Djibouti. The Emperor would be left with a truncated Empire composed of Shewa and Wollo, with bits and pieces of the Tigrean and Oromo territories.

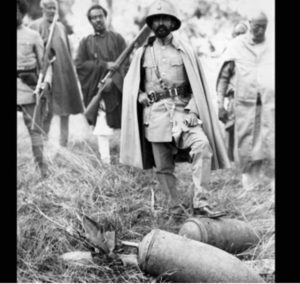

He would be firmly placed under an Italian protectorate. The Hoare/Laval plan was denounced by supporters of the Ethiopian cause in Europe when it was leaked, and the Ethiopians were generally scandalized. This plan was rejected by the Emperor. The Emperor had no choice left to him but to try and fight an enemy that had massive material resources prepared to defeat him. The great negarit (war drum) of Menelik was beaten at the Palace in Addis Ababa, and war was formally declared. Thousands of irregulars mostly armed with old guns from the last century and swords, spears and shields, marched north to confront the huge Italian force which was equipped with modern tanks, machine guns, artillery and airplanes armed with bombs and poison gas.

useless. The Foreign Ministers of France and Britain (Laval and Hoare) were secretly negotiating a solution that would involve Ethiopia handing over the Ogaden and most of Tigrai to the Italians, grant English hegemony over the basin of the Blue Nile, and the French control of the area adjacent to the railroad to Djibouti. The Emperor would be left with a truncated Empire composed of Shewa and Wollo, with bits and pieces of the Tigrean and Oromo territories.

He would be firmly placed under an Italian protectorate. The Hoare/Laval plan was denounced by supporters of the Ethiopian cause in Europe when it was leaked, and the Ethiopians were generally scandalized. This plan was rejected by the Emperor. The Emperor had no choice left to him but to try and fight an enemy that had massive material resources prepared to defeat him. The great negarit (war drum) of Menelik was beaten at the Palace in Addis Ababa, and war was formally declared. Thousands of irregulars mostly armed with old guns from the last century and swords, spears and shields, marched north to confront the huge Italian force which was equipped with modern tanks, machine guns, artillery and airplanes armed with bombs and poison gas.

Even the modern regular army created by the Emperor was ill equipped to face this technological onslaught. The soldiers even marched barefoot. Emperor Haile Selassie at this point knew that a military solution was futile, but he was determined to fight on militarily and diplomatically until such time as he hoped the League acted. Empress Menen mobilized the women of Addis Ababa in making bandages and provisions for the soldiers. She presided over the Ethiopian Red Cross and became its patron. The Emperor established his northern front headquarters at Dessie, and commanded the troops against the Italians. The Italians in the north were led by Marshal De Bono, a senior officer of the Royal Italian army with weak ties to the Fascist hierarchy. His cautious and slow approach to the invasion of northern Ethiopia was regarded with deep impatience by Mussolini who believed that De Bono was dragging his feet. In the meantime, Ethiopian Imperial family was horrified when they learned that the Emperor’s son-in-law, Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa had crossed over to the Italians.

Even the modern regular army created by the Emperor was ill equipped to face this technological onslaught. The soldiers even marched barefoot. Emperor Haile Selassie at this point knew that a military solution was futile, but he was determined to fight on militarily and diplomatically until such time as he hoped the League acted. Empress Menen mobilized the women of Addis Ababa in making bandages and provisions for the soldiers. She presided over the Ethiopian Red Cross and became its patron. The Emperor established his northern front headquarters at Dessie, and commanded the troops against the Italians. The Italians in the north were led by Marshal De Bono, a senior officer of the Royal Italian army with weak ties to the Fascist hierarchy. His cautious and slow approach to the invasion of northern Ethiopia was regarded with deep impatience by Mussolini who believed that De Bono was dragging his feet. In the meantime, Ethiopian Imperial family was horrified when they learned that the Emperor’s son-in-law, Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa had crossed over to the Italians.

Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa was the husband of the late Princess Zenebework, and the great-grandson of Emperor Yohannis IV. His action is said to have been caused by his resentment at not having been made king of Tigrai, or at least Ras. This act of betrayal caused him to still be remembered in Ethiopia as the ultimate traitor against his country. The Tigrean locals looted his home in Mekele in anger.

Photographs were taken of him sitting at a table looking over maps with Marshal De Bono and his staff and publicized by the Italians, to show Ethiopian nobles that they could expect good treatment if they collaborated with the Fascists. In the meantime, Ethiopian troops were being pounded by tanks, heavy artillery, airplanes and finally poison gas and liquids.

Use of poison gas had been strictly prohibited by the Geneva conventions, yet the world did nothing to stop Italy. Special spraying mechanisms were installed on the aircraft so that poisonous substances could be sprayed directly onto the land, poisoning not just soldiers, but peasants, cattle, fields and bodies of water. Italy even bombed Red Cross ambulances and clearly marked treatment camps that were run by the British and French Red Cross.

Dejazmatch Haile Selassie Gugsa was the husband of the late Princess Zenebework, and the great-grandson of Emperor Yohannis IV. His action is said to have been caused by his resentment at not having been made king of Tigrai, or at least Ras. This act of betrayal caused him to still be remembered in Ethiopia as the ultimate traitor against his country. The Tigrean locals looted his home in Mekele in anger.

Photographs were taken of him sitting at a table looking over maps with Marshal De Bono and his staff and publicized by the Italians, to show Ethiopian nobles that they could expect good treatment if they collaborated with the Fascists. In the meantime, Ethiopian troops were being pounded by tanks, heavy artillery, airplanes and finally poison gas and liquids.

Use of poison gas had been strictly prohibited by the Geneva conventions, yet the world did nothing to stop Italy. Special spraying mechanisms were installed on the aircraft so that poisonous substances could be sprayed directly onto the land, poisoning not just soldiers, but peasants, cattle, fields and bodies of water. Italy even bombed Red Cross ambulances and clearly marked treatment camps that were run by the British and French Red Cross.

Rases Imiru, Kassa, Seyum, Getachew and Mulugueta; led armies in the north that fought valiantly but was beaten back by the slow advance of De Bono and his well-armed troops. Impatient with the slow pace of the war, Mussolini removed De Bono and replaced him with Marshal Badoglio.

As the Italians battled through Tigrai and northern Beghemidir with the forces of Rases Seyoum, Imiru, and Kassa, the Emperor assembled his forces and prepared to meet the fascist invader at Mai Chew in southern Tigrai. Shortly before the battle, the Emperor is said to have given a great traditional Giber Feast in a cave near Mai Chew. Some believe that constant delays in attacking the Italians cost the Ethiopian side the element of surprise at Mai Chew. Although they fought valiantly, it was in vain, and the Ethiopian forces were smashed by the Italians and began to retreat in haste. Taking this opportunity, Raya and Azebo tribesmen attacked the retreating forces of the Emperor in revenge for a recent raid to stop them from raiding and rustling cattle, and in anger over the just announced death of Lij Eyasu who many of them still regarded as their rightful monarch.

Oddly, while the army retreated in disarray, the Emperor seemed to retreat in leisure. He did not retreat with the army, but behind it, a dangerous situation that upset some of his advisers as dangerous opening him up for possible capture. The monarch had perhaps given up on earthly powers and was turning to higher

Rases Imiru, Kassa, Seyum, Getachew and Mulugueta; led armies in the north that fought valiantly but was beaten back by the slow advance of De Bono and his well-armed troops. Impatient with the slow pace of the war, Mussolini removed De Bono and replaced him with Marshal Badoglio.

As the Italians battled through Tigrai and northern Beghemidir with the forces of Rases Seyoum, Imiru, and Kassa, the Emperor assembled his forces and prepared to meet the fascist invader at Mai Chew in southern Tigrai. Shortly before the battle, the Emperor is said to have given a great traditional Giber Feast in a cave near Mai Chew. Some believe that constant delays in attacking the Italians cost the Ethiopian side the element of surprise at Mai Chew. Although they fought valiantly, it was in vain, and the Ethiopian forces were smashed by the Italians and began to retreat in haste. Taking this opportunity, Raya and Azebo tribesmen attacked the retreating forces of the Emperor in revenge for a recent raid to stop them from raiding and rustling cattle, and in anger over the just announced death of Lij Eyasu who many of them still regarded as their rightful monarch.

Oddly, while the army retreated in disarray, the Emperor seemed to retreat in leisure. He did not retreat with the army, but behind it, a dangerous situation that upset some of his advisers as dangerous opening him up for possible capture. The monarch had perhaps given up on earthly powers and was turning to higher  authorities. Emperor Haile Selassie paid a secret visit to the churches at Lalibella to pray, taking the time to visit the distant church of Our Lady at the summit of Mt. Asheten as well.

This trip was a huge detour that extended his retreat considerably and dangerously. Finally, the Emperor finished his prayers and then proceeded out of Wello and on to Addis Ababa. Upon his arrival an emergency meeting of war leaders and nobles was held at the palace to decide what the next action should be. It was agreed that Addis Ababa would be impossible to defend, and that in the interests of preserving the Imperial house, the Empress and the Imperial family should immediately leave for Djibouti, and board an English ship for Palestine. A debate was held as to what the Emperor himself and the government should do. Some believed that it would be best to relocate the government to Gore, in the remote south. The Emperor agreed with this and ordered that it be done immediately.

It was then discussed whether it would be wise for the Emperor to move with the government to Gore, and fight on, or leave with his family and presents the plea of the Ethiopian people in person before the League of Nations in Geneva. One of his long-time supporters and fellow modernist, Blatta Takkele angrily stated that an Ethiopian Emperor had never fled a battle, and that Emperor Haile Selassie should die in the glory of battle rather than go into exile and beg for the help of European

authorities. Emperor Haile Selassie paid a secret visit to the churches at Lalibella to pray, taking the time to visit the distant church of Our Lady at the summit of Mt. Asheten as well.

This trip was a huge detour that extended his retreat considerably and dangerously. Finally, the Emperor finished his prayers and then proceeded out of Wello and on to Addis Ababa. Upon his arrival an emergency meeting of war leaders and nobles was held at the palace to decide what the next action should be. It was agreed that Addis Ababa would be impossible to defend, and that in the interests of preserving the Imperial house, the Empress and the Imperial family should immediately leave for Djibouti, and board an English ship for Palestine. A debate was held as to what the Emperor himself and the government should do. Some believed that it would be best to relocate the government to Gore, in the remote south. The Emperor agreed with this and ordered that it be done immediately.

It was then discussed whether it would be wise for the Emperor to move with the government to Gore, and fight on, or leave with his family and presents the plea of the Ethiopian people in person before the League of Nations in Geneva. One of his long-time supporters and fellow modernist, Blatta Takkele angrily stated that an Ethiopian Emperor had never fled a battle, and that Emperor Haile Selassie should die in the glory of battle rather than go into exile and beg for the help of European  colonialists. Ironically, it was the chief voice of conservatism, Ras Kassa Hailu, who just as forcefully argued against this traditionalist position championed by a modernist.

The premier prince of the blood argued that if the Emperor stayed and was killed or captured, the cause of Ethiopia would be finished as the forces of opposition to the Italians fragmented. By staying alive and safe abroad, he could appeal for assistance from a position of legitimacy and return some day to fight again, keeping hope alive for the resistance. Empress Menen also pulled the Emperor aside and stressed her agreement with this position. She added that he should come with her to Jerusalem and pray for the deliverance of their country with her.

Blatta Takelle is said to have horrified the assembled courtiers by threatening to draw his gun and saying that he would rather shoot the Emperor himself rather

colonialists. Ironically, it was the chief voice of conservatism, Ras Kassa Hailu, who just as forcefully argued against this traditionalist position championed by a modernist.

The premier prince of the blood argued that if the Emperor stayed and was killed or captured, the cause of Ethiopia would be finished as the forces of opposition to the Italians fragmented. By staying alive and safe abroad, he could appeal for assistance from a position of legitimacy and return some day to fight again, keeping hope alive for the resistance. Empress Menen also pulled the Emperor aside and stressed her agreement with this position. She added that he should come with her to Jerusalem and pray for the deliverance of their country with her.

Blatta Takelle is said to have horrified the assembled courtiers by threatening to draw his gun and saying that he would rather shoot the Emperor himself rather  than have his country abandoned by her king. The Emperor made his decision. On the morning of May 3rd, 1936, The Emperor with Empress Menen, Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen with Crown Princess Wollete Israel and Princess Ijigayehu their daughter; Princess Tenagnework and her children, Princesses Aida, Seble, Sophia, Hirut, Princes Amha and Iskinder Desta; Princess Tsehai; Prince Makonnen Duke of Harrar; and Prince Sahle Selassie; along with numerous nobles and officials boarded the train to Djibouti. Crowds assembled to see them off, and as the train pulled out, the crowds began to wail. When news that the Emperor had fled began to spread, panic began to set in. The government had packed up and departed hurriedly for Gore.

The Emperor had appointed his cousin Ras Imiru as Prince-Regent and

than have his country abandoned by her king. The Emperor made his decision. On the morning of May 3rd, 1936, The Emperor with Empress Menen, Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen with Crown Princess Wollete Israel and Princess Ijigayehu their daughter; Princess Tenagnework and her children, Princesses Aida, Seble, Sophia, Hirut, Princes Amha and Iskinder Desta; Princess Tsehai; Prince Makonnen Duke of Harrar; and Prince Sahle Selassie; along with numerous nobles and officials boarded the train to Djibouti. Crowds assembled to see them off, and as the train pulled out, the crowds began to wail. When news that the Emperor had fled began to spread, panic began to set in. The government had packed up and departed hurriedly for Gore.

The Emperor had appointed his cousin Ras Imiru as Prince-Regent and  Commander-in-Chief. Ras Desta Damtew, the Emperor’s son-in-law and husband of Princess Tenagnework was to continue in command of the Imperial forces in the south. The remnants of the northern Armies were directed to join him or Ras Imiru immediately. Dejazmatch Beyene Merid, husband of the Emperor’s eldest daughter, Princess Romanework (from his first marriage) remained in command of troops in Bale, under the general command of Ras Desta. Princess Romanework and her two little sons remained behind with the Dejazmatch rather than go into exile.

The chief of the Addis Ababa police, Balambaras (later Ras) Abebe Aregai began to organize a guerrilla army, set fire to key structures that he didn’t want the

Commander-in-Chief. Ras Desta Damtew, the Emperor’s son-in-law and husband of Princess Tenagnework was to continue in command of the Imperial forces in the south. The remnants of the northern Armies were directed to join him or Ras Imiru immediately. Dejazmatch Beyene Merid, husband of the Emperor’s eldest daughter, Princess Romanework (from his first marriage) remained in command of troops in Bale, under the general command of Ras Desta. Princess Romanework and her two little sons remained behind with the Dejazmatch rather than go into exile.

The chief of the Addis Ababa police, Balambaras (later Ras) Abebe Aregai began to organize a guerrilla army, set fire to key structures that he didn’t want the  Italians to seize and marched out of the city. With the departure of the Imperial family, the exit of the government and of the army and police forces, disorder began to take root as the residents realized that the city had no authorities and was on the verge of falling to the hated Italians. Many began to loot and burn stores and warehouses, and foreign nationals fled to the safety of the compounds of the various diplomatic missions.

On May 5th, 1936, the armies of fascist Italy, led by Marshal Pietro Badoglio marched into Addis Ababa and occupied the city. Promptly, that very day, Benito Mussolini went out onto the balcony of the Venezia Palace in Rome and declared that “Ethiopia is Italian” before huge throngs of cheering Romans. The King of Italy emerged on the balcony as the dictator proclaimed him Vittorio Emannuelle, King of Italy and Emperor of Ethiopia before the wildly cheering masses.

The new “King-Emperor” of the new “Italian Empire” in gratitude bestowed the title of “Duke of Addis Ababa” as a hereditary title upon Marshal Badoglio, and Marchese of Neghelli on Marshal Graziani, the commander of the Italian troops that seized Harrar. Mussolini appointed Badoglio as the Vice-Roy (Vice-re) in what would henceforth be referred to as “Africa Orientale Italiana” or Italian East Africa, and would combine Ethiopia with the Old Italian colonies of Somaliland and Eritrea.

The title of Niguse Negest (King of Kings) which had been used by the Emperors of Ethiopia was forbidden to be used for the King of Italy. His new Imperial title over Ethiopia would be Keasare Ityopia (Caesar of Ethiopia) in an echo of Italian pretensions to ancient empire. The Italian flag was raised over the palace of Menelik, and the Italians began to set up colonial administration as they continued the military campaign to stamp out the resistance in the south.

Italians to seize and marched out of the city. With the departure of the Imperial family, the exit of the government and of the army and police forces, disorder began to take root as the residents realized that the city had no authorities and was on the verge of falling to the hated Italians. Many began to loot and burn stores and warehouses, and foreign nationals fled to the safety of the compounds of the various diplomatic missions.

On May 5th, 1936, the armies of fascist Italy, led by Marshal Pietro Badoglio marched into Addis Ababa and occupied the city. Promptly, that very day, Benito Mussolini went out onto the balcony of the Venezia Palace in Rome and declared that “Ethiopia is Italian” before huge throngs of cheering Romans. The King of Italy emerged on the balcony as the dictator proclaimed him Vittorio Emannuelle, King of Italy and Emperor of Ethiopia before the wildly cheering masses.

The new “King-Emperor” of the new “Italian Empire” in gratitude bestowed the title of “Duke of Addis Ababa” as a hereditary title upon Marshal Badoglio, and Marchese of Neghelli on Marshal Graziani, the commander of the Italian troops that seized Harrar. Mussolini appointed Badoglio as the Vice-Roy (Vice-re) in what would henceforth be referred to as “Africa Orientale Italiana” or Italian East Africa, and would combine Ethiopia with the Old Italian colonies of Somaliland and Eritrea.

The title of Niguse Negest (King of Kings) which had been used by the Emperors of Ethiopia was forbidden to be used for the King of Italy. His new Imperial title over Ethiopia would be Keasare Ityopia (Caesar of Ethiopia) in an echo of Italian pretensions to ancient empire. The Italian flag was raised over the palace of Menelik, and the Italians began to set up colonial administration as they continued the military campaign to stamp out the resistance in the south.

In the meantime, Emperor Haile Selassie and his family were entering Djibouti. As the Emperor had left, he had ordered two prominent prisoners be brought to him and be put on the train. The Imperial train had stopped at Dire Dawa, where the Emperor had these prisoners brought before him. They were Ras Hailu Tekle Haimanot, the disgraced Prince of Gojjam, and Dejazmatch Balcha Saffo, the great general of Adowa and servant of Menelik who had tried to rebel against the then King Taffari on behalf of Empress Zewditu and the conservatives.

He addressed these prisoners by telling them that although he recognized that they did not favour him, he hoped that their love of their country would guide them in their actions, and he released them. Ras Hailu promptly boarded a train for Addis Ababa and submitted to the Italian forces. He would serve them loyally for the duration of the occupation, and in return he was recognized as the senior “native noble”. Dejazmatch Balcha however was a man of a different calibre.

Although aged and very bitter towards the Emperor (whom he continued to contemptuously refer to as Taffari), he retained a strong love of his country, an unshakable loyalty to Emperor Menelik, and a deep hatred of Italy going back to the Adowa campaign. He and a band of followers became guerrilla fighters who harassed and made life difficult for the Italian occupiers for months on end. Finally, when his troops were almost all dead, and he himself was exhausted and

In the meantime, Emperor Haile Selassie and his family were entering Djibouti. As the Emperor had left, he had ordered two prominent prisoners be brought to him and be put on the train. The Imperial train had stopped at Dire Dawa, where the Emperor had these prisoners brought before him. They were Ras Hailu Tekle Haimanot, the disgraced Prince of Gojjam, and Dejazmatch Balcha Saffo, the great general of Adowa and servant of Menelik who had tried to rebel against the then King Taffari on behalf of Empress Zewditu and the conservatives.

He addressed these prisoners by telling them that although he recognized that they did not favour him, he hoped that their love of their country would guide them in their actions, and he released them. Ras Hailu promptly boarded a train for Addis Ababa and submitted to the Italian forces. He would serve them loyally for the duration of the occupation, and in return he was recognized as the senior “native noble”. Dejazmatch Balcha however was a man of a different calibre.

Although aged and very bitter towards the Emperor (whom he continued to contemptuously refer to as Taffari), he retained a strong love of his country, an unshakable loyalty to Emperor Menelik, and a deep hatred of Italy going back to the Adowa campaign. He and a band of followers became guerrilla fighters who harassed and made life difficult for the Italian occupiers for months on end. Finally, when his troops were almost all dead, and he himself was exhausted and  had little hope of success, Dejazmatch Balcha sent a message to the local Italian commander near Harrar and announced that he was prepared to surrender to him and to meet at a specific locale. The officer, accompanied by an appropriate guard in dress uniform went to receive the surrender. The found the old Oromo nobleman, wrapped in a traditional white shawl, sitting under a large tree. As they approached him, he cried out to “Menelik my master” and pulled out a machine gun, killing all the senior officers before being gunned down himself. He is upheld as a great hero of the resistance to this day.

Film exists of the arrival of the Imperial family of Ethiopia and their retinue at Djibouti. They received a state welcome by the French Governor of the colony. The Empress is shown wearing a large hat covered by a heavy veil, but eye witness accounts state that she wept through the whole proceedings. Two trains had arrived in Djibouti carrying many people into exile with the family. Ethiopians resident in the French colony lined the roads in Djibouti to see for themselves if indeed the Imperial family had gone into exile for the first time in history. When they saw that it was indeed a sombre Haile Selassie, and a weeping Empress, being driven past them, they too were seen to weep according to the Illustrated Times of

had little hope of success, Dejazmatch Balcha sent a message to the local Italian commander near Harrar and announced that he was prepared to surrender to him and to meet at a specific locale. The officer, accompanied by an appropriate guard in dress uniform went to receive the surrender. The found the old Oromo nobleman, wrapped in a traditional white shawl, sitting under a large tree. As they approached him, he cried out to “Menelik my master” and pulled out a machine gun, killing all the senior officers before being gunned down himself. He is upheld as a great hero of the resistance to this day.

Film exists of the arrival of the Imperial family of Ethiopia and their retinue at Djibouti. They received a state welcome by the French Governor of the colony. The Empress is shown wearing a large hat covered by a heavy veil, but eye witness accounts state that she wept through the whole proceedings. Two trains had arrived in Djibouti carrying many people into exile with the family. Ethiopians resident in the French colony lined the roads in Djibouti to see for themselves if indeed the Imperial family had gone into exile for the first time in history. When they saw that it was indeed a sombre Haile Selassie, and a weeping Empress, being driven past them, they too were seen to weep according to the Illustrated Times of  London. An English ship HMS Enterprise in Palestine had been directed to pick up the Emperor of Ethiopia and convey him to Palestine.

When the ship arrived, it was determined that not all of the people that had gone into exile with the Emperor would be allowed to board the ship for Palestine, and when the Imperial family and a small group of followers (about half of those who had arrived on the two trains) boarded the ship and set sail, those anguished people left behind stood on the docks and wailed and wept as the monarch departed.

The Emperor relates in his autobiography how some Ethiopian men and women resident in Egypt rented a boat as his ship passed through Port Said, and sailed next to it waving an Ethiopian flag. When he came out on deck to acknowledge them, he saw them break down and weep, the incident moved him deeply. The Illustrated Times of London printed photographs of the Imperial couple arriving at

London. An English ship HMS Enterprise in Palestine had been directed to pick up the Emperor of Ethiopia and convey him to Palestine.

When the ship arrived, it was determined that not all of the people that had gone into exile with the Emperor would be allowed to board the ship for Palestine, and when the Imperial family and a small group of followers (about half of those who had arrived on the two trains) boarded the ship and set sail, those anguished people left behind stood on the docks and wailed and wept as the monarch departed.

The Emperor relates in his autobiography how some Ethiopian men and women resident in Egypt rented a boat as his ship passed through Port Said, and sailed next to it waving an Ethiopian flag. When he came out on deck to acknowledge them, he saw them break down and weep, the incident moved him deeply. The Illustrated Times of London printed photographs of the Imperial couple arriving at  Haifa, the Emperor and Empress looking dejected. They proceeded to Jerusalem to pray, and to settle in while the Emperor prepared to present Ethiopia’s case to the League of Nations at Geneva.

The Emperor and his entourage were determined to make a stand against Italy at the League of Nations. Although France and the United Kingdom had continued to press Ethiopia to accept partition, and now that the Italians had marched into the capital, both these powers were leaning heavily towards recognizing Italian rule over Ethiopia, the Emperor had a strong case to be heard, and they could do little to prevent Ethiopia from presenting her case.

Although the French had received him in Djibouti with all the pomp of a visiting monarch, his arrival in Palestine and later in Britain had been treated as the

Haifa, the Emperor and Empress looking dejected. They proceeded to Jerusalem to pray, and to settle in while the Emperor prepared to present Ethiopia’s case to the League of Nations at Geneva.

The Emperor and his entourage were determined to make a stand against Italy at the League of Nations. Although France and the United Kingdom had continued to press Ethiopia to accept partition, and now that the Italians had marched into the capital, both these powers were leaning heavily towards recognizing Italian rule over Ethiopia, the Emperor had a strong case to be heard, and they could do little to prevent Ethiopia from presenting her case.

Although the French had received him in Djibouti with all the pomp of a visiting monarch, his arrival in Palestine and later in Britain had been treated as the  arrival of a private person, and no official notice was taken of the event. Hundreds of anti-fascists however chose to make their presence felt by thronging the docks upon the Emperor’s arrival in England, and by crowding around various places he visited to pay their respects. Many roadblocks were set up though to make it difficult.

The Italians spread rumours that the Imperial family had fled with tons of gold and silver, that the Emperor had ordered the torching of Addis Ababa and the butchering of the people. In reality, the Emperor had left to prevent a bloodbath in the city, and he had left with little money, although he did take with him his crown and the old war tent of Emperor Menelik to prevent it from falling into the hands of the fascists. The Emperor arrived in Geneva to address the League of Nations in person. He was the first head of state to appear before the assembly, and the only one who would ever address it. The assembly of the League of Nations was being presided over by the Romanian delegate. The galleries above the floor of the assembly were packed with journalists, many of whom were Italians. When “His

arrival of a private person, and no official notice was taken of the event. Hundreds of anti-fascists however chose to make their presence felt by thronging the docks upon the Emperor’s arrival in England, and by crowding around various places he visited to pay their respects. Many roadblocks were set up though to make it difficult.

The Italians spread rumours that the Imperial family had fled with tons of gold and silver, that the Emperor had ordered the torching of Addis Ababa and the butchering of the people. In reality, the Emperor had left to prevent a bloodbath in the city, and he had left with little money, although he did take with him his crown and the old war tent of Emperor Menelik to prevent it from falling into the hands of the fascists. The Emperor arrived in Geneva to address the League of Nations in person. He was the first head of state to appear before the assembly, and the only one who would ever address it. The assembly of the League of Nations was being presided over by the Romanian delegate. The galleries above the floor of the assembly were packed with journalists, many of whom were Italians. When “His  Majesty the Emperor of Ethiopia” was announced, the Italian journalists in the gallery began to whistle, stomp their feet and jeer loudly. The Emperor quietly walked up to the podium and stood quietly, a small man in a black cape looking up at the loudly protesting Italians silently. The angry president of the session, the delegate from Romania (who was chairing the session) lost his temper and demanded that the security personnel “Remove the savages!”, and the Italians were removed from the galleries. The Emperor then began his historic speech. The Emperor, although fluent in French, spoke in Amharic. He traced the history of the conflict and the atrocities committed by the Italians. He told of the horrors of poison gas attacks and the death rained on his people. He appealed to the League to follow through on its guarantees of collective security, and the promise that small and weak countries would not be allowed to be the victims of the large and strong.

In spite of his victory in the battle for public opinion, the League of Nations did little however to help the Emperor, beyond weak symbolic sanctions that had little effect on Italy. Although the League did recognize the government at Gore, and did not accept the Italian argument that the Ethiopian Empire ceased to exist due to their conquest, Great Britain, France and the United States all gave recognition to the Italian conquest of Ethiopia by acknowledging King Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy as Emperor of Ethiopia.

The League accepted the Emperor’s argument that the Ethiopian government continued to exist at Gore, and permitted the Ethiopian delegation to continue to sit in the League and represent that government.

The Emperor departed for Britain to begin his new life in exile. He was assisted in

Majesty the Emperor of Ethiopia” was announced, the Italian journalists in the gallery began to whistle, stomp their feet and jeer loudly. The Emperor quietly walked up to the podium and stood quietly, a small man in a black cape looking up at the loudly protesting Italians silently. The angry president of the session, the delegate from Romania (who was chairing the session) lost his temper and demanded that the security personnel “Remove the savages!”, and the Italians were removed from the galleries. The Emperor then began his historic speech. The Emperor, although fluent in French, spoke in Amharic. He traced the history of the conflict and the atrocities committed by the Italians. He told of the horrors of poison gas attacks and the death rained on his people. He appealed to the League to follow through on its guarantees of collective security, and the promise that small and weak countries would not be allowed to be the victims of the large and strong.

In spite of his victory in the battle for public opinion, the League of Nations did little however to help the Emperor, beyond weak symbolic sanctions that had little effect on Italy. Although the League did recognize the government at Gore, and did not accept the Italian argument that the Ethiopian Empire ceased to exist due to their conquest, Great Britain, France and the United States all gave recognition to the Italian conquest of Ethiopia by acknowledging King Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy as Emperor of Ethiopia.

The League accepted the Emperor’s argument that the Ethiopian government continued to exist at Gore, and permitted the Ethiopian delegation to continue to sit in the League and represent that government.

The Emperor departed for Britain to begin his new life in exile. He was assisted in  his work by Lorenzo Taezaz, and Eritrean born loyalist who acted as his primary representative to the league and a frequent go between with exiles and resistance fighters. Azaj Workineh Eshete (Dr. Charles Martin), the Ethiopian minister to Great Britain was also an active participant in raising funds and publicity for the cause of Ethiopia. Blatangueta Hirui, the elderly foreign minister of Ethiopia worked also towards liberation from exile, until his death in London in 1937.

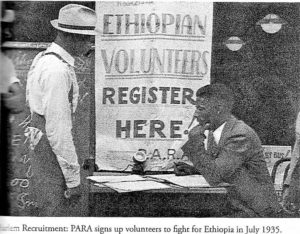

Notwithstanding the tepid response of the League of Nations to the fascist invasion of Ethiopia; Italian imperialism in Ethiopia provoked an outburst of international concern, sympathy and outright protest from the general public. Private Citizens the world over condemned and denounced Italy’s violation of Ethiopian sovereignty. Although universal in scope, public condemnation of the Italian invasion was particularly sharp amongst the blacks in the United States, who had long drawn inspiration from classical and modern Ethiopia as a symbol of black power and pride.

his work by Lorenzo Taezaz, and Eritrean born loyalist who acted as his primary representative to the league and a frequent go between with exiles and resistance fighters. Azaj Workineh Eshete (Dr. Charles Martin), the Ethiopian minister to Great Britain was also an active participant in raising funds and publicity for the cause of Ethiopia. Blatangueta Hirui, the elderly foreign minister of Ethiopia worked also towards liberation from exile, until his death in London in 1937.

Notwithstanding the tepid response of the League of Nations to the fascist invasion of Ethiopia; Italian imperialism in Ethiopia provoked an outburst of international concern, sympathy and outright protest from the general public. Private Citizens the world over condemned and denounced Italy’s violation of Ethiopian sovereignty. Although universal in scope, public condemnation of the Italian invasion was particularly sharp amongst the blacks in the United States, who had long drawn inspiration from classical and modern Ethiopia as a symbol of black power and pride.

As the distinguished black historian indicated, “When Italy invaded Ethiopia,

They (Afro-Americans) protested with all the means at their command. Almost overnight even the most provincial among the American Negroes became internationally minded. Ethiopia was (regarded as) a Negro nation and its destruction would symbolize the final victory of the white man over the Negro.” Many organisations sprung up in Harlem the main area where efforts were concentrated; one example being the Menilek Club formed by public-spirited black citizens in 1936. This very small but spirited group desired to integrate all of the existing Ethiopian Aid societies into one organisation officially recognised by the Ethiopian Authorities. The efforts of the group culminated with a delegation being sent to England in the summer of 1936 to confer directly with Haile Selassie I, who

As the distinguished black historian indicated, “When Italy invaded Ethiopia,

They (Afro-Americans) protested with all the means at their command. Almost overnight even the most provincial among the American Negroes became internationally minded. Ethiopia was (regarded as) a Negro nation and its destruction would symbolize the final victory of the white man over the Negro.” Many organisations sprung up in Harlem the main area where efforts were concentrated; one example being the Menilek Club formed by public-spirited black citizens in 1936. This very small but spirited group desired to integrate all of the existing Ethiopian Aid societies into one organisation officially recognised by the Ethiopian Authorities. The efforts of the group culminated with a delegation being sent to England in the summer of 1936 to confer directly with Haile Selassie I, who  received them at his residence Fairfield House in Bath. The mission consisted of three prominent Harlem figures, all leaders of the black organisation known as the United Aid for Ethiopia: Reverend William Lloyd Imes, pastor of the prestigious St. James Presbyterian, Philip M. Savoy, chairman of the Victory Insurance Company and co-owner of the New York Amsterdam News, and Mr Cyril M Philp, secretary of the United Aid. The delegation stressed to the monarch the necessity of sending a special emissary to America to direct the collection of all contributions and to help awaken flagging Afro-American support for the Ethiopian cause. Impressed Haile Selassie decided to despatch an envoy to the United States. He selected his personal physician, Dr. Malaku Emanuel Bayen, for the new position. Later events were to prove that the emperor could not have made a better choice.

received them at his residence Fairfield House in Bath. The mission consisted of three prominent Harlem figures, all leaders of the black organisation known as the United Aid for Ethiopia: Reverend William Lloyd Imes, pastor of the prestigious St. James Presbyterian, Philip M. Savoy, chairman of the Victory Insurance Company and co-owner of the New York Amsterdam News, and Mr Cyril M Philp, secretary of the United Aid. The delegation stressed to the monarch the necessity of sending a special emissary to America to direct the collection of all contributions and to help awaken flagging Afro-American support for the Ethiopian cause. Impressed Haile Selassie decided to despatch an envoy to the United States. He selected his personal physician, Dr. Malaku Emanuel Bayen, for the new position. Later events were to prove that the emperor could not have made a better choice.

The son of the Gerazmatch (Baron) Bayen and Waizero (Lady) Desta, Malaku Bayen was born on April 29, 1900, in Wollo Province in central Ethiopia. At six months of age, he was taken by his parents to the city of Harar, where he grew up in the palace of Ras (Grand Duke) Tafari Makonnen, his mother’s first cousin and the future emperor of Ethiopia. In accordance with the aristo- cracy’s custom of educating and training likely young boys for positions of leadership, young Bayen was placed under the tutelage of his prominent and powerful relative and taught by priests, attached to Ras Tafari’s palace.

In 1921, when Tafari was selecting young Ethiopian men and women to be educated abroad, Bayen was among the first to be chosen. “I was told of my responsibility by His Majesty himself; that I was to study medicine and return to Ethiopia as a physician for the purpose of helping to organize the Public Health System . . . ,” After being sent to Bombay, India with three colleagues, two young men and a woman, for preparatory studies under private tutors from Great Britain. The group decided “America was the only country that would never try to rob us of our country; therefore it would be best to go there.” The tiny group thereupon prevailed upon their benefactor, Ras Tarari, to permit them to pursue their studies in the United States, where imperialistic designs on Africa seemed absent. Much to their probable relief and delight, the students’ request was granted. Thus, within the short span of one year they were preparing to travel to yet another far-off land of whose existence most of their countrymen were only dimly aware. Bayen passed his examinations at Howard University and was graduated from its medical school in June 1935. In London, Dr. Bayen served as the exiled sovereign’s personal physician, interpreter, secretary, and in other capacities demanded by those trying times.

As the special emissary to America of Haile Selassie; Dr Bayen and his family arrived in New York on September 23, 1936. Dr Bayen had married Dora Hadley

The son of the Gerazmatch (Baron) Bayen and Waizero (Lady) Desta, Malaku Bayen was born on April 29, 1900, in Wollo Province in central Ethiopia. At six months of age, he was taken by his parents to the city of Harar, where he grew up in the palace of Ras (Grand Duke) Tafari Makonnen, his mother’s first cousin and the future emperor of Ethiopia. In accordance with the aristo- cracy’s custom of educating and training likely young boys for positions of leadership, young Bayen was placed under the tutelage of his prominent and powerful relative and taught by priests, attached to Ras Tafari’s palace.

In 1921, when Tafari was selecting young Ethiopian men and women to be educated abroad, Bayen was among the first to be chosen. “I was told of my responsibility by His Majesty himself; that I was to study medicine and return to Ethiopia as a physician for the purpose of helping to organize the Public Health System . . . ,” After being sent to Bombay, India with three colleagues, two young men and a woman, for preparatory studies under private tutors from Great Britain. The group decided “America was the only country that would never try to rob us of our country; therefore it would be best to go there.” The tiny group thereupon prevailed upon their benefactor, Ras Tarari, to permit them to pursue their studies in the United States, where imperialistic designs on Africa seemed absent. Much to their probable relief and delight, the students’ request was granted. Thus, within the short span of one year they were preparing to travel to yet another far-off land of whose existence most of their countrymen were only dimly aware. Bayen passed his examinations at Howard University and was graduated from its medical school in June 1935. In London, Dr. Bayen served as the exiled sovereign’s personal physician, interpreter, secretary, and in other capacities demanded by those trying times.

As the special emissary to America of Haile Selassie; Dr Bayen and his family arrived in New York on September 23, 1936. Dr Bayen had married Dora Hadley  whom he met at Howard university infact it was at Howard university where Malaku formally annulled his engagement to a daughter of the Ethiopian Foreign Minister and met his future wife, Dorothy, as she handed him his registration card. Dorothy and Malaku were married, 1931 in Fairfax, Virginia. In 1933, the couple welcomed their son, Malaku Bayen, Jr. For several years, the family lived in Adis Ababa. Living in several locations while Dr. Bayen was out on the battlefields and serving the Emperor in a variety of capacities, Dorothy tended to home life around town and at the palace. Dorothy also served as War Correspondent for the African-American press under the title “Princess Malaku Bayen”.

Bayen wasted no time in establishing contact with New York’s Afro- American community. On September 28, 1936, just five days after his return to the United

whom he met at Howard university infact it was at Howard university where Malaku formally annulled his engagement to a daughter of the Ethiopian Foreign Minister and met his future wife, Dorothy, as she handed him his registration card. Dorothy and Malaku were married, 1931 in Fairfax, Virginia. In 1933, the couple welcomed their son, Malaku Bayen, Jr. For several years, the family lived in Adis Ababa. Living in several locations while Dr. Bayen was out on the battlefields and serving the Emperor in a variety of capacities, Dorothy tended to home life around town and at the palace. Dorothy also served as War Correspondent for the African-American press under the title “Princess Malaku Bayen”.

Bayen wasted no time in establishing contact with New York’s Afro- American community. On September 28, 1936, just five days after his return to the United  States, the physician addressed a gathering of two thousand at Harlem’s Rockland Palace, a popular meeting place, then as well as now, for black nationalists. In a rousing speech, the Ethiopian delegate informed the crowd that his country was not conquered and never would be. Declaring that, “We will never give up,” Bayen told the audience that, “our soldiers will never cease fighting until the enemy is driven from our soil.” The gathering went “wild with joy ” and, according to the doctor, many of those present proceeded to work with him ” in the interest of Ethiopia and the Black Race . . . ” Dr. Bayen had been working in conjunction with the United Aid for Ethiopia, which was the most active of the few remaining Ethiopian aid associations. During much of this period and even prior to Bayen’s involvement, the organization, under the leadership of Reverend William Imes, seems to have been performing well. In fact, one glowing report maintained that it had “functioned perfectly well for a while. “The situation began to change, however as members of the American Communist Party took sharp interest in the United Aid and attempted to transform it into a Communist front.

Wanting to be free of any entanglement with the “Reds,” whether black or white, Bayen and others decided to form an entirely new organization to be known as the Ethiopian World Federation. Consequently, the United Aid was dissolved, a number of similar groups were combined, and a new more substantial organization with Malaku Bayen as its executive head was formally created on August 25, 1937. Dr. Lorenzo H. King, pastor of St. Mark’s Methodist Church in Harlem, was elected the Federation’s first president.

Concerning itself mainly with aiding the thousands of Ethiopian refugees living in Egypt, French Somaliland, Kenya, Sudan, and elsewhere, but possessing broader political objectives than its predecessor, the Federation became a national organization. Assisted in its recruiting efforts by its weekly tabloid, the Voice of Ethiopia (in which the term “Negro ” was proscribed), the organization conducted propaganda meetings in nearly every American city with a sizeable Afro-American population. It also dispatched members to cities less well populated with blacks to establish locals. It was reported in July, 1938 that the Federation had founded ten locals in the United States and had another twenty-two applications pending. By 1940, there were twenty-two actual branches in existence, some of which were located in Latin America and the West Indies; its membership was said to be in the thousands. Considerable funds were raised to help the victims of the war, and to keep open Ethiopian Embassy’s worldwide.

In a letter to the organization from the “Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Haile Selassie I, Elect of God, Emperor of Ethiopia after the war his majesty wrote;

States, the physician addressed a gathering of two thousand at Harlem’s Rockland Palace, a popular meeting place, then as well as now, for black nationalists. In a rousing speech, the Ethiopian delegate informed the crowd that his country was not conquered and never would be. Declaring that, “We will never give up,” Bayen told the audience that, “our soldiers will never cease fighting until the enemy is driven from our soil.” The gathering went “wild with joy ” and, according to the doctor, many of those present proceeded to work with him ” in the interest of Ethiopia and the Black Race . . . ” Dr. Bayen had been working in conjunction with the United Aid for Ethiopia, which was the most active of the few remaining Ethiopian aid associations. During much of this period and even prior to Bayen’s involvement, the organization, under the leadership of Reverend William Imes, seems to have been performing well. In fact, one glowing report maintained that it had “functioned perfectly well for a while. “The situation began to change, however as members of the American Communist Party took sharp interest in the United Aid and attempted to transform it into a Communist front.

Wanting to be free of any entanglement with the “Reds,” whether black or white, Bayen and others decided to form an entirely new organization to be known as the Ethiopian World Federation. Consequently, the United Aid was dissolved, a number of similar groups were combined, and a new more substantial organization with Malaku Bayen as its executive head was formally created on August 25, 1937. Dr. Lorenzo H. King, pastor of St. Mark’s Methodist Church in Harlem, was elected the Federation’s first president.

Concerning itself mainly with aiding the thousands of Ethiopian refugees living in Egypt, French Somaliland, Kenya, Sudan, and elsewhere, but possessing broader political objectives than its predecessor, the Federation became a national organization. Assisted in its recruiting efforts by its weekly tabloid, the Voice of Ethiopia (in which the term “Negro ” was proscribed), the organization conducted propaganda meetings in nearly every American city with a sizeable Afro-American population. It also dispatched members to cities less well populated with blacks to establish locals. It was reported in July, 1938 that the Federation had founded ten locals in the United States and had another twenty-two applications pending. By 1940, there were twenty-two actual branches in existence, some of which were located in Latin America and the West Indies; its membership was said to be in the thousands. Considerable funds were raised to help the victims of the war, and to keep open Ethiopian Embassy’s worldwide.

In a letter to the organization from the “Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Haile Selassie I, Elect of God, Emperor of Ethiopia after the war his majesty wrote;

“Salutations! This letter expresses the token of my warmest appreciation for the aid and sympathy evinced by you and your fellows in the hour of Ethiopia’s crisis. During those eventful years and since, I have never ceased to think of these benevolences nor of the spirit which impelled you to act in such a charitable a manner to my beloved country and her righteous cause.

These are the years of strenuous efforts to bridge the gulf between the years of war, occupation and the interruption of, the normal life of Ethiopia. It is my sincerest wish, however, that through our mutual efforts, the future would prove beneficial to the relations between you and the people of this land.”

In September 1955 during EWF International Organizer Mrs Mamie Richardson, visits Jamaica. According to The Daily Gleaner, Ms Richardson announced that: 500 acres of land was granted through the EWF to the Black people of the West who aided Ethiopia during her period of distress. The land was the personal property of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I.

Back in Ethiopia the Italians were settling in. The Italians took possession of the capital and set about building the foundations for their new administration. The former colonies of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland were merged with Ethiopia to form what they called “Africa Orientale Italiana” or “AOI”, a single colony ruled from Addis Ababa by the Vice-Roy as the representative of the King-Emperor (Kesare) and the Deuce Mussolini. As administrative units, the Empire was restructured into new regions that replaced the old Imperial provinces.

The Fascist doctrine of conquest was based on an ideology of revenge for the humiliation of Adowa, and the erasing of Ethiopian national identity. The Italians looted what they could of Ethiopia’s heritage. Several crowns of previous monarchs

“Salutations! This letter expresses the token of my warmest appreciation for the aid and sympathy evinced by you and your fellows in the hour of Ethiopia’s crisis. During those eventful years and since, I have never ceased to think of these benevolences nor of the spirit which impelled you to act in such a charitable a manner to my beloved country and her righteous cause.

These are the years of strenuous efforts to bridge the gulf between the years of war, occupation and the interruption of, the normal life of Ethiopia. It is my sincerest wish, however, that through our mutual efforts, the future would prove beneficial to the relations between you and the people of this land.”

In September 1955 during EWF International Organizer Mrs Mamie Richardson, visits Jamaica. According to The Daily Gleaner, Ms Richardson announced that: 500 acres of land was granted through the EWF to the Black people of the West who aided Ethiopia during her period of distress. The land was the personal property of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I.

Back in Ethiopia the Italians were settling in. The Italians took possession of the capital and set about building the foundations for their new administration. The former colonies of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland were merged with Ethiopia to form what they called “Africa Orientale Italiana” or “AOI”, a single colony ruled from Addis Ababa by the Vice-Roy as the representative of the King-Emperor (Kesare) and the Deuce Mussolini. As administrative units, the Empire was restructured into new regions that replaced the old Imperial provinces.

The Fascist doctrine of conquest was based on an ideology of revenge for the humiliation of Adowa, and the erasing of Ethiopian national identity. The Italians looted what they could of Ethiopia’s heritage. Several crowns of previous monarchs  were taken to Italy on Mussolini’s orders. Marshal Pietro Badoglio showed one crown to the English writer Evlyn Waugh (a fascist sympathizer) to confirm that this was in fact the crown of Emperor Haile Selassie, whose coronation Waugh had attended five years earlier.

Waugh confirmed that the silver gilt crown was indeed the crown of Emperor Haile Selassie, but she was mistaken. The crown used at the coronation in 1930 was solid gold, not silver gilt, and had accompanied the Imperial family into exile. The Italians carried off the taller of the two standing obelisks at Axum, and erected it in Rome in front of the Ministry of the Colonies (the headquarters for the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization today) where it stood for decades until it was returned in 2006.

During the visit to Addis Ababa by the Minister for the Colonies, Lessona, he ordered several other monuments removed also. Taken to Rome was the Lion of Judah monument from in front of the Addis Ababa train station. The lion was re-erected in Rome next to the Vittorio Emanuelle monument.

The Italians also removed the statue of Emperor Menelik from the square in front of St. George’s Cathedral and also the crown from the top of the dome of the St. Marys Ba’eta monastery where Menelik II was buried. These two large monuments of the Ethiopian monarchy were removed in the dead of night, and taken out of the city and hidden. The next morning, people came out into the streets of the city and saw the empty pedestal of the statue of Emperor Menelik, and many are said to have beaten their chests and wept as if at a funeral of a relative. The Italians took a host of valuable works of art, manuscripts, and the entire Imperial archives and took them to Italy. They also took the Emperor’s Ethiopian assembled airplane, the “Princess Tsehai” named after his daughter. After a few months as the Vice-Roy of the “King-Emperor Vittorio Emanuelle III”, Marshal Badoglio, “Duke of Addis Ababa” resigned and returned to Rome, where he could better bask in the glory of being the conqueror of Italy’s new Empire. More of a monarchist than a staunch fascist, he found himself in constant battles with the Minister for the Colonies, Lessona, over ideological and jurisdictional issues.

were taken to Italy on Mussolini’s orders. Marshal Pietro Badoglio showed one crown to the English writer Evlyn Waugh (a fascist sympathizer) to confirm that this was in fact the crown of Emperor Haile Selassie, whose coronation Waugh had attended five years earlier.

Waugh confirmed that the silver gilt crown was indeed the crown of Emperor Haile Selassie, but she was mistaken. The crown used at the coronation in 1930 was solid gold, not silver gilt, and had accompanied the Imperial family into exile. The Italians carried off the taller of the two standing obelisks at Axum, and erected it in Rome in front of the Ministry of the Colonies (the headquarters for the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization today) where it stood for decades until it was returned in 2006.

During the visit to Addis Ababa by the Minister for the Colonies, Lessona, he ordered several other monuments removed also. Taken to Rome was the Lion of Judah monument from in front of the Addis Ababa train station. The lion was re-erected in Rome next to the Vittorio Emanuelle monument.

The Italians also removed the statue of Emperor Menelik from the square in front of St. George’s Cathedral and also the crown from the top of the dome of the St. Marys Ba’eta monastery where Menelik II was buried. These two large monuments of the Ethiopian monarchy were removed in the dead of night, and taken out of the city and hidden. The next morning, people came out into the streets of the city and saw the empty pedestal of the statue of Emperor Menelik, and many are said to have beaten their chests and wept as if at a funeral of a relative. The Italians took a host of valuable works of art, manuscripts, and the entire Imperial archives and took them to Italy. They also took the Emperor’s Ethiopian assembled airplane, the “Princess Tsehai” named after his daughter. After a few months as the Vice-Roy of the “King-Emperor Vittorio Emanuelle III”, Marshal Badoglio, “Duke of Addis Ababa” resigned and returned to Rome, where he could better bask in the glory of being the conqueror of Italy’s new Empire. More of a monarchist than a staunch fascist, he found himself in constant battles with the Minister for the Colonies, Lessona, over ideological and jurisdictional issues.

He was replaced as Vice-Roy by Marshal Graziani, a staunch fascist, and a man with a long and bloody reputation from his ruthless suppression of rebels in Italian ruled Libya. Although the Italians had proclaimed a new “Fascist Empire”, Ethiopia was hardly conquered and pacified. Wide stretches of the countryside remained outside Italian control, and would remain so for the duration of the occupation. Although all the major urban areas were firmly occupied, rural areas remained restive and alive with anti-Fascist activity. The armies of Ras Imiru and Ras Desta remained in the south, very actively opposing the Italians. Guerrillas were banding together in the central and northern highlands as well. In particular, Abebe Arregai in Shewa, Belai Zelleke in Gojjam, and “Amoraw (The Hawk)” Wubineh in Beghemidir led well organized guerrilla forces that harassed and bloodied the Italians again and again, making it impossible for them to ever fully extend Fascist rule.

Remnants of the Imperial army however were determined to oust the Italians from Addis Ababa. The scattered brigades needed someone to lead them, and coordinate with the guerrillas. Soon, the rumours swept through Addis Ababa, that the Imperial red umbrellas had been seen in Menz to the north. The House of Solomon was far from finished. In Menz, the sons of the premier prince of the blood, Ras Kassa Hailu, were rallying the peasantry to the banner of the dynasty. Dejazmatch Wondwossen Kassa, Dejazmatch Abera Kassa, and Dejazmatch Asfaw Wossen Kassa began to gather the remnants of the Imperial forces and many more peasants’ urban intelegencia who had fled the occupation of the cities into a new

He was replaced as Vice-Roy by Marshal Graziani, a staunch fascist, and a man with a long and bloody reputation from his ruthless suppression of rebels in Italian ruled Libya. Although the Italians had proclaimed a new “Fascist Empire”, Ethiopia was hardly conquered and pacified. Wide stretches of the countryside remained outside Italian control, and would remain so for the duration of the occupation. Although all the major urban areas were firmly occupied, rural areas remained restive and alive with anti-Fascist activity. The armies of Ras Imiru and Ras Desta remained in the south, very actively opposing the Italians. Guerrillas were banding together in the central and northern highlands as well. In particular, Abebe Arregai in Shewa, Belai Zelleke in Gojjam, and “Amoraw (The Hawk)” Wubineh in Beghemidir led well organized guerrilla forces that harassed and bloodied the Italians again and again, making it impossible for them to ever fully extend Fascist rule.

Remnants of the Imperial army however were determined to oust the Italians from Addis Ababa. The scattered brigades needed someone to lead them, and coordinate with the guerrillas. Soon, the rumours swept through Addis Ababa, that the Imperial red umbrellas had been seen in Menz to the north. The House of Solomon was far from finished. In Menz, the sons of the premier prince of the blood, Ras Kassa Hailu, were rallying the peasantry to the banner of the dynasty. Dejazmatch Wondwossen Kassa, Dejazmatch Abera Kassa, and Dejazmatch Asfaw Wossen Kassa began to gather the remnants of the Imperial forces and many more peasants’ urban intelegencia who had fled the occupation of the cities into a new  army. With them was the Bishop of Wollo, Abune Petros himself, who rallied the population and exhorted them to refuse the rule of this godless enemy.

The three royal Dejazmatches captured the imagination of the Shewan loyalists of the dynasty, and plans were set up to expel the Italians from Addis Ababa.

By the time the Italian army had Addis Ababa under its control and Mussolini had declared Ethiopia part of the Italian Empire on 9 May 1936,

Only a section of the northern part of the country was firmly under their control. ‘Five months after the defeat of Emperor Haile Selassie, Badoglio and Graziani controlled only one third of the country’. After the Battle of Maichew, resistance commenced more or less immediately. Many groups from the defeated army went into the bush and started resistance actions. Throughout the occupation period these Patriots remained active and made life difficult for the Italians especially in rural northern, eastern and central Ethiopia. The country was thus never effectively occupied or colonized.

army. With them was the Bishop of Wollo, Abune Petros himself, who rallied the population and exhorted them to refuse the rule of this godless enemy.

The three royal Dejazmatches captured the imagination of the Shewan loyalists of the dynasty, and plans were set up to expel the Italians from Addis Ababa.

By the time the Italian army had Addis Ababa under its control and Mussolini had declared Ethiopia part of the Italian Empire on 9 May 1936,