The Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated- History

The Beginnings

American Ethiopian Connection

Numerous references to Ethiopia in the Bible, such as (Psalm 68:31) “…Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hands unto God,” provided refuge and salvation for Negro slaves in America and the Caribbean. During the American Revolutionary War, one African-American regiment proudly wears the appellation of “Allen’s Ethiopians,” named after Bishop Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Church in Philadelphia.

America and the Caribbean. During the American Revolutionary War, one African-American regiment proudly wears the appellation of “Allen’s Ethiopians,” named after Bishop Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Church in Philadelphia.

As African Americans fixed their gaze on Ethiopia, Abyssinians also travelled to the ‘New World’ and learned of the African presence in the Americas. In 1808 merchants from Abyssinia (Ethiopia) arrived at New York’s famous Wall Street. While attempting to attend church services at the First Baptist Church of New York, the Abyssinian merchants, along with their African American colleagues, experienced the on-going routine of racial discrimination. As an act of defiance against segregation in a house of worship, African Americans and Abyssinians organized their own church on Worth Street in Lower Manhattan and named it Abyssinia Baptist Church.

Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. served as the first preacher, and new building was later purchased on Waverly Place in the West Village before the church was moved to its current location in Harlem. Scholar Fikru Negash Gebrekidan likewise notes that, along with such literal acts of rebellion, anti-slavery leaders Robert Alexander Young and David Walker published pamphlets entitled Ethiopian Manifesto and Appeal in 1829 in an effort to galvanize blacks to rise against their slave masters.

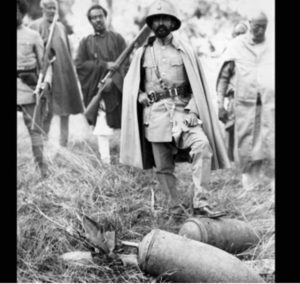

When Italian colonialists encroached on Abyssinian territory and were soundly defeated in the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, it became the first African victory over a European colonial power, and the victories resounded loud and clear among compatriots of the black

As African Americans fixed their gaze on Ethiopia, Abyssinians also travelled to the ‘New World’ and learned of the African presence in the Americas. In 1808 merchants from Abyssinia (Ethiopia) arrived at New York’s famous Wall Street. While attempting to attend church services at the First Baptist Church of New York, the Abyssinian merchants, along with their African American colleagues, experienced the on-going routine of racial discrimination. As an act of defiance against segregation in a house of worship, African Americans and Abyssinians organized their own church on Worth Street in Lower Manhattan and named it Abyssinia Baptist Church.

Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. served as the first preacher, and new building was later purchased on Waverly Place in the West Village before the church was moved to its current location in Harlem. Scholar Fikru Negash Gebrekidan likewise notes that, along with such literal acts of rebellion, anti-slavery leaders Robert Alexander Young and David Walker published pamphlets entitled Ethiopian Manifesto and Appeal in 1829 in an effort to galvanize blacks to rise against their slave masters.

When Italian colonialists encroached on Abyssinian territory and were soundly defeated in the Battle of Adwa on March 1, 1896, it became the first African victory over a European colonial power, and the victories resounded loud and clear among compatriots of the black diaspora. “For the oppressed masses Adwa…would become a cause célèbre,” writes Gebrekidan, “a metaphor for racial pride and anti-colonial defiance, living proof that skin colour or hair texture bore no significance on intellect and character.” Soon, African Americans and blacks from the Caribbean Islands began to make their way to Abyssinia. In 1903, accompanied by Haitian poet and traveller Benito Sylvain, an affluent African American business magnate by the name of William Henry Ellis arrived in Abyssinia to greet and make acquaintances with Emperor Menelik. A Treaty of Amity (Friendship) and Commerce between Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia and Robert P. Skinner for the United States was signed. Ellis recounts to the Emperor the great Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln and America’s interest in trade as opposed to colonization. The Treaty is duly proclaimed by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

A prominent physician from the West Indies, Dr. Joseph Vitalien, also journeyed to Abyssinia and eventually became the Emperor’ trusted personal physician.

In 1909 Daniel Robert Alexander, who was born in Missouri and lived in Chicago, becomes the first African-American settler from the United States on record in Abyssinia.

diaspora. “For the oppressed masses Adwa…would become a cause célèbre,” writes Gebrekidan, “a metaphor for racial pride and anti-colonial defiance, living proof that skin colour or hair texture bore no significance on intellect and character.” Soon, African Americans and blacks from the Caribbean Islands began to make their way to Abyssinia. In 1903, accompanied by Haitian poet and traveller Benito Sylvain, an affluent African American business magnate by the name of William Henry Ellis arrived in Abyssinia to greet and make acquaintances with Emperor Menelik. A Treaty of Amity (Friendship) and Commerce between Emperor Menelik II of Abyssinia and Robert P. Skinner for the United States was signed. Ellis recounts to the Emperor the great Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln and America’s interest in trade as opposed to colonization. The Treaty is duly proclaimed by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.

A prominent physician from the West Indies, Dr. Joseph Vitalien, also journeyed to Abyssinia and eventually became the Emperor’ trusted personal physician.

In 1909 Daniel Robert Alexander, who was born in Missouri and lived in Chicago, becomes the first African-American settler from the United States on record in Abyssinia.

In 1919 the first official Abyssinian delegation to the United States visits New York City, Washington, DC and Chicago. At the time Woodrow Wilson was serving as the 28th President of the United States. In Abyssinia, Empress Zawditu, the eldest daughter of Emperor Menelik, was the reigning monarch. The main purpose of their trip was to renew the 1904 Treaty of Amity (Friendship) between the United States and Abyssinia (brokered when President Theodore Roosevelt authorized 37-year-old Robert P. Skinner to negotiate a commercial treaty with Emperor Menelik). The treaty had expired in 1917. This four-man delegation to the United States became known as the Abyssinian mission. The distinguished delegation headed to the White House in Washington D.C. after staying at the elegant Waldorf-Astoria in Chicago.

The group visited the U.S. at a time when blacks were by law second-class citizens and the most common crime against American blacks was lynching. Before leaving Chicago, a reporter for the Chicago Defender, an African American newspaper, asked the delegation what they thought about lynching in the U.S. The representatives responded “We dislike brutality… lynching of any nature, and other outrages heaped upon your people.”

African-Americans were inspired to see a proud African delegation being treated with so much respect by U.S. officials. Newspapers reported that in honour of the delegation’s visit “the flag of Abyssinia, which is of green, yellow, and red horizontal stripes, flew over the national capitol.”

The Mission, under authority of Ras Taffari, extends the first invitation to Africans in America to repatriate to Abyssinia. African-Americans are astonished at how well respected the Abyssinian delegation is treated in that “Jim Crow” era.

In 1919 the first official Abyssinian delegation to the United States visits New York City, Washington, DC and Chicago. At the time Woodrow Wilson was serving as the 28th President of the United States. In Abyssinia, Empress Zawditu, the eldest daughter of Emperor Menelik, was the reigning monarch. The main purpose of their trip was to renew the 1904 Treaty of Amity (Friendship) between the United States and Abyssinia (brokered when President Theodore Roosevelt authorized 37-year-old Robert P. Skinner to negotiate a commercial treaty with Emperor Menelik). The treaty had expired in 1917. This four-man delegation to the United States became known as the Abyssinian mission. The distinguished delegation headed to the White House in Washington D.C. after staying at the elegant Waldorf-Astoria in Chicago.

The group visited the U.S. at a time when blacks were by law second-class citizens and the most common crime against American blacks was lynching. Before leaving Chicago, a reporter for the Chicago Defender, an African American newspaper, asked the delegation what they thought about lynching in the U.S. The representatives responded “We dislike brutality… lynching of any nature, and other outrages heaped upon your people.”

African-Americans were inspired to see a proud African delegation being treated with so much respect by U.S. officials. Newspapers reported that in honour of the delegation’s visit “the flag of Abyssinia, which is of green, yellow, and red horizontal stripes, flew over the national capitol.”

The Mission, under authority of Ras Taffari, extends the first invitation to Africans in America to repatriate to Abyssinia. African-Americans are astonished at how well respected the Abyssinian delegation is treated in that “Jim Crow” era.

In 1920 Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford, Harlem’s African-American Jewish leader and musical director of the United Negro Improvement Association, composes the song “Ethiopia Awaken” that becomes the anthem for the Ethiopian World Federation.

The announced coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930 as the first black ruler of an African nation in modern times raised the hopes of black people all over the world and led Rabbi Ford to believe that the timing of his Abyssinian colony was providential. The Abyssinia government had been encouraging black people with skills and education to immigrate to Abyssinia for almost a decade, Ford took up this invitation and arrived in Abyssinia with a small musical contingent in time to perform during the coronation festivities.

Mignon Innis arrived with a second delegation in 1931 to work as Ford’s private secretary. She soon became Ford’s wife, and they had two children in Abyssinia.

Ford’s wife, Mignon T. Ford would later found Princess Zennebe Worq High School, which was the first secondary school for girls in Abyssinia.

In November 1930, Ras Taffari Makonnen was crowned Emperor of Abyssinia. The event blared on radios, and Harlemites heard and marvelled at the ceremonies of a black king. The emperor’s face glossed the cover of Time Magazine, which remarked on “negro news organs” in America hailing the king “as their own.” African American pilot Hubert Julian, dubbed “The Black Eagle of Harlem,” had visited Abyssinia and attended the coronation. Describing the momentous occasion to Time Magazine, Hubert rhapsodized:

In 1920 Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford, Harlem’s African-American Jewish leader and musical director of the United Negro Improvement Association, composes the song “Ethiopia Awaken” that becomes the anthem for the Ethiopian World Federation.

The announced coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930 as the first black ruler of an African nation in modern times raised the hopes of black people all over the world and led Rabbi Ford to believe that the timing of his Abyssinian colony was providential. The Abyssinia government had been encouraging black people with skills and education to immigrate to Abyssinia for almost a decade, Ford took up this invitation and arrived in Abyssinia with a small musical contingent in time to perform during the coronation festivities.

Mignon Innis arrived with a second delegation in 1931 to work as Ford’s private secretary. She soon became Ford’s wife, and they had two children in Abyssinia.

Ford’s wife, Mignon T. Ford would later found Princess Zennebe Worq High School, which was the first secondary school for girls in Abyssinia.

In November 1930, Ras Taffari Makonnen was crowned Emperor of Abyssinia. The event blared on radios, and Harlemites heard and marvelled at the ceremonies of a black king. The emperor’s face glossed the cover of Time Magazine, which remarked on “negro news organs” in America hailing the king “as their own.” African American pilot Hubert Julian, dubbed “The Black Eagle of Harlem,” had visited Abyssinia and attended the coronation. Describing the momentous occasion to Time Magazine, Hubert rhapsodized:

“When I arrived in Ethiopia the King was glad to see me… I took off with a French pilot… We climbed to 5,000 ft. as 50,000 people cheered, and then I jumped out and tugged open my parachute… I floated down to within 40 ft. of the King, who incidentally is the greatest of all modern rulers… He rushed up and pinned the highest medal given in that country on my breast, made me a colonel and the leader of his air force — and here I am!”

Emperor Haile Selassie began an aggressive programme of modernization and centralization of the structure of the state. He ordered the drafting of the first written constitution for the Empire, which was completed and promulgated in 1931. The First Imperial Constitution, which borrowed heavily from the Meiji Constitution of Japan, provided for a Parliament for the first time in Abyssinian History. It is in this first constitution that the Emperor officially renamed the name of his country from Abyssinia to Ethiopia, after recognising the political significance of the name Ethiopia and especially its Christian Biblical connections. The name of Ethiopia represents the Greek word for its native inhabitants. This was “aithiops” (= “burnt appearance”), from “aitho” (I burn) and “opsis” (aspect, appearance). It was now possible for all black peoples living abroad to associate themselves as, being Ethiopians abroad.

“When I arrived in Ethiopia the King was glad to see me… I took off with a French pilot… We climbed to 5,000 ft. as 50,000 people cheered, and then I jumped out and tugged open my parachute… I floated down to within 40 ft. of the King, who incidentally is the greatest of all modern rulers… He rushed up and pinned the highest medal given in that country on my breast, made me a colonel and the leader of his air force — and here I am!”

Emperor Haile Selassie began an aggressive programme of modernization and centralization of the structure of the state. He ordered the drafting of the first written constitution for the Empire, which was completed and promulgated in 1931. The First Imperial Constitution, which borrowed heavily from the Meiji Constitution of Japan, provided for a Parliament for the first time in Abyssinian History. It is in this first constitution that the Emperor officially renamed the name of his country from Abyssinia to Ethiopia, after recognising the political significance of the name Ethiopia and especially its Christian Biblical connections. The name of Ethiopia represents the Greek word for its native inhabitants. This was “aithiops” (= “burnt appearance”), from “aitho” (I burn) and “opsis” (aspect, appearance). It was now possible for all black peoples living abroad to associate themselves as, being Ethiopians abroad.

Melaku Beyan was a member of the primary batch of students sent to America in the 1930s. He attended Ohio State University and later received his medical degree at Howard Medical School in Washington, D.C. During his schooling years at Howard, he forged lasting friendships with members of the black community and, at Emperor Haile Selassie’s request; he endeavoured to enlist African American professionals to work in Ethiopia. Beyan was successful in recruiting several individuals, including teachers Joseph Hall and William Jackson, as well as physicians Dr. John West and Dr. Reuben S. Young, the latter of whom began a private practice in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, prior to his official assignment as a municipal health officer in Dire Dawa, Harar.

Italio – Ethiopian War

By the mid-1930s the Emperor had sent a second diplomatic mission to the U.S. Vexed at Italy’s consistently aggressive behaviour towards his nation, Haile Selassie attempted to forge stronger ties with America. Despite being a member of the League of Nations, Italy disregarded international law and invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Melaku Beyan left the United States and travelled to Britain where he became the personal physician of Haile Selassie I who had taken up residence in exile at Fairfield House in Bath.

Melaku Beyan was a member of the primary batch of students sent to America in the 1930s. He attended Ohio State University and later received his medical degree at Howard Medical School in Washington, D.C. During his schooling years at Howard, he forged lasting friendships with members of the black community and, at Emperor Haile Selassie’s request; he endeavoured to enlist African American professionals to work in Ethiopia. Beyan was successful in recruiting several individuals, including teachers Joseph Hall and William Jackson, as well as physicians Dr. John West and Dr. Reuben S. Young, the latter of whom began a private practice in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, prior to his official assignment as a municipal health officer in Dire Dawa, Harar.

Italio – Ethiopian War

By the mid-1930s the Emperor had sent a second diplomatic mission to the U.S. Vexed at Italy’s consistently aggressive behaviour towards his nation, Haile Selassie attempted to forge stronger ties with America. Despite being a member of the League of Nations, Italy disregarded international law and invaded Ethiopia in 1935. Melaku Beyan left the United States and travelled to Britain where he became the personal physician of Haile Selassie I who had taken up residence in exile at Fairfield House in Bath.

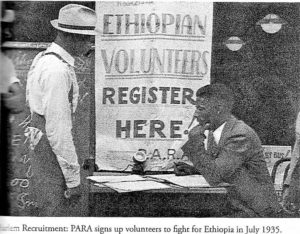

Notwithstanding the tepid response of the League of Nations to the fascist invasion of Ethiopia; Italian imperialism in Ethiopia provoked an outburst of international concern, sympathy and outright protest from the general public. Private Citizens the world over condemned and denounced Italy’s violation of Ethiopian sovereignty. Although universal in scope, public condemnation of the Italian invasion was particularly sharp amongst the blacks in the United States, who had long drawn inspiration from classical and modern Ethiopia as a symbol of black power and pride.

As an distinguished black historian indicated, “When Italy invaded Ethiopia,

They (Afro-Americans) protested with all the means at their command. Almost overnight even the most provincial among the American Negroes became internationally minded.

Notwithstanding the tepid response of the League of Nations to the fascist invasion of Ethiopia; Italian imperialism in Ethiopia provoked an outburst of international concern, sympathy and outright protest from the general public. Private Citizens the world over condemned and denounced Italy’s violation of Ethiopian sovereignty. Although universal in scope, public condemnation of the Italian invasion was particularly sharp amongst the blacks in the United States, who had long drawn inspiration from classical and modern Ethiopia as a symbol of black power and pride.

As an distinguished black historian indicated, “When Italy invaded Ethiopia,

They (Afro-Americans) protested with all the means at their command. Almost overnight even the most provincial among the American Negroes became internationally minded.

Ethiopia was (regarded as) a Negro nation and its destruction would symbolize the final victory of the white man over the Negro.” Many organisations sprung up in Harlem the main area where efforts were concentrated; one example being the Menilek Club formed by public-spirited black citizens in 1936. This very small but spirited group desired to integrate all of the existing Ethiopian Aid societies into one organisation officially recognised by the Ethiopian Authorities. The efforts of the group culminated with a delegation being sent to England in the summer of 1936 to confer directly with Haile Selassie I, who received them at his residence Fairfield House in Bath.

Ethiopia was (regarded as) a Negro nation and its destruction would symbolize the final victory of the white man over the Negro.” Many organisations sprung up in Harlem the main area where efforts were concentrated; one example being the Menilek Club formed by public-spirited black citizens in 1936. This very small but spirited group desired to integrate all of the existing Ethiopian Aid societies into one organisation officially recognised by the Ethiopian Authorities. The efforts of the group culminated with a delegation being sent to England in the summer of 1936 to confer directly with Haile Selassie I, who received them at his residence Fairfield House in Bath.

The mission consisted of three prominent Harlem figures, all leaders of the black organisation known as the United Aid for Ethiopia: Reverend William Lloyd Imes, pastor of the prestigious St. James Presbyterian, Philip M. Savoy, chairman of the Victory Insurance Company and co-owner of the New York Amsterdam News, and Mr Cyril M Philp, secretary of the United Aid. The delegation stressed to the monarch the necessity of sending a special emissary to America to direct the collection of all contributions and to help awaken flagging Afro-American support for the Ethiopian cause. Impressed Haile Selassie decided to despatch an envoy to the United States. He selected his personal physician, Dr. Malaku Emanuel Bayen, for the new position. Later events were to prove that the emperor could not have made a better choice.

Melaku Beyan was a young, charismatic speaker. Beyan had married an African American activist, Dorothy Hadley, and together they created a newspaper called Voice of Ethiopia to simultaneously denounce Jim Crow in America and fascist invasion in Ethiopia. Joel Rogers, the correspondent who had previously attended the Emperor’s coronation, returned to Ethiopia as a war correspondent for The Pittsburgh Courier, then America’s most widely-circulated black newspaper. Upon returning to the United States a year later, he published a pamphlet entitled The Real Facts about Ethiopia, a scathing and uncompromising report on the destruction caused by Italian troops in Ethiopia. Melaku Beyan used the pamphlet in his speaking tours, while his wife Dorothy designed and passed out pins that read “Save Ethiopia.”

Dr. Bayen had been working in conjunction with the United Aid for Ethiopia, which was the most active of the few remaining Ethiopian aid associations. During much of this period and even prior to Bayen’s involvement, the organization, under the leadership of Reverend William Imes, seems to have been performing well. In fact, one glowing report maintained that it had “functioned perfectly well for a while.

“The situation began to change, however as members of the American Communist Party took sharp interest in the United Aid and attempted to transform it into a Communist front.

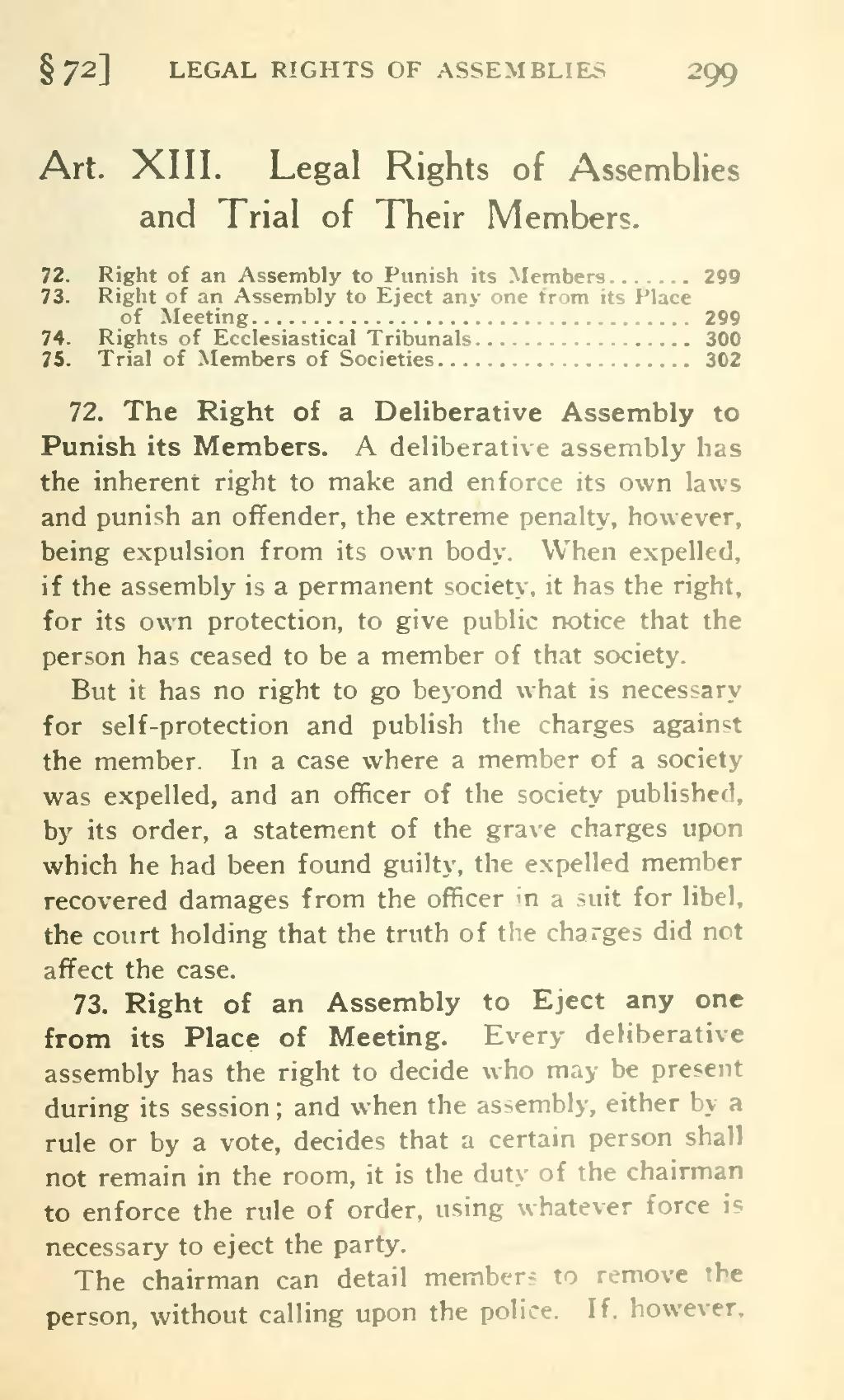

Wanting to be free of any entanglement with the “Reds,” whether black or white, Bayen and others decided to form an entirely new organization to be known as the Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated. Consequently, the United Aid was dissolved, a number of similar groups were combined, and a new more substantial organization with Malaku Bayen as its executive head was formally created on August 25, 1937. Dr. Lorenzo H. King, pastor of St. Mark’s Methodist Church in Harlem, was elected the Federation’s first president.

Its Preamble being;

The mission consisted of three prominent Harlem figures, all leaders of the black organisation known as the United Aid for Ethiopia: Reverend William Lloyd Imes, pastor of the prestigious St. James Presbyterian, Philip M. Savoy, chairman of the Victory Insurance Company and co-owner of the New York Amsterdam News, and Mr Cyril M Philp, secretary of the United Aid. The delegation stressed to the monarch the necessity of sending a special emissary to America to direct the collection of all contributions and to help awaken flagging Afro-American support for the Ethiopian cause. Impressed Haile Selassie decided to despatch an envoy to the United States. He selected his personal physician, Dr. Malaku Emanuel Bayen, for the new position. Later events were to prove that the emperor could not have made a better choice.

Melaku Beyan was a young, charismatic speaker. Beyan had married an African American activist, Dorothy Hadley, and together they created a newspaper called Voice of Ethiopia to simultaneously denounce Jim Crow in America and fascist invasion in Ethiopia. Joel Rogers, the correspondent who had previously attended the Emperor’s coronation, returned to Ethiopia as a war correspondent for The Pittsburgh Courier, then America’s most widely-circulated black newspaper. Upon returning to the United States a year later, he published a pamphlet entitled The Real Facts about Ethiopia, a scathing and uncompromising report on the destruction caused by Italian troops in Ethiopia. Melaku Beyan used the pamphlet in his speaking tours, while his wife Dorothy designed and passed out pins that read “Save Ethiopia.”

Dr. Bayen had been working in conjunction with the United Aid for Ethiopia, which was the most active of the few remaining Ethiopian aid associations. During much of this period and even prior to Bayen’s involvement, the organization, under the leadership of Reverend William Imes, seems to have been performing well. In fact, one glowing report maintained that it had “functioned perfectly well for a while.

“The situation began to change, however as members of the American Communist Party took sharp interest in the United Aid and attempted to transform it into a Communist front.

Wanting to be free of any entanglement with the “Reds,” whether black or white, Bayen and others decided to form an entirely new organization to be known as the Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated. Consequently, the United Aid was dissolved, a number of similar groups were combined, and a new more substantial organization with Malaku Bayen as its executive head was formally created on August 25, 1937. Dr. Lorenzo H. King, pastor of St. Mark’s Methodist Church in Harlem, was elected the Federation’s first president.

Its Preamble being;

“We, the Black Peoples of the World, in order to effect Unity, Solidarity, Liberty, Freedom and Self-determination, to secure Justice and maintain the Integrity of Ethiopia, which is our divine heritage, do hereby establish and ordain this Constitution for the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated.”

Its Aims and Objects being;

(a). To promote love and good-will among Ethiopians at home and abroad and thereby to maintain the integrity and sovereignty of Ethiopia, to disseminate the ancient Ethiopian culture among its members, to correct abuses, relieve oppression and carve for ourselves and our posterity, a destiny comparable with our idea of perfect manhood and God’s purpose in creating us; that we may not only save ourselves from annihilation, but carve for ourselves a place in the Sun: in this endeavour, we determine to seek peace and pursue it., for it is the will of God for man.

(b): To promote and pursue happiness; for it is the goal of human life and endeavour.

(c): To usher in the teaching and practice of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.

(d): To promote and stimulate interest among its members in world affairs, and to cultivate a spirit of international goodwill and comity.

(e): To promote friendly interest among its members, to develop a fraternal spirit among them and to inculcate in its members’ the desire to render voluntary aid and assistance to one another at all times.

(f): To render voluntary aid and protection to its members, without fee or charge for same when in need. And, if necessary, to provide and care for refugees and disabled victims of the Italio-Ethiopian War.

(g): To give concrete material and voluntary aid without fee or charge for the same, to all such refugees and disabled victims and to raise funds by voluntary subscription for the purposes aforementioned. There shall be no charge, fee, beneficiary tax or other assessment upon the members of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated, except for dues, provided for in the Constitution and By-Laws of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated.

(h) To encourage its members to develop interest and pride in Democratic institutions and to promote Democratic principles and ideals. May God help us to accomplish these aims and ideals?

Concerning itself mainly with aiding the thousands of Ethiopian refugees living in Egypt, French Somaliland, Kenya, Sudan, and elsewhere, but possessing broader political objectives than its predecessor, the Ethiopian World Federation became a national organization. Assisted in its recruiting efforts by its weekly tabloid, the Voice of Ethiopia (in which the term “Negro ” was proscribed), the organization conducted propaganda meetings in nearly every American city with a sizeable Afro-American population. It also dispatched members to cities less well populated with blacks to establish locals. It was reported in July, 1938 that the Federation had founded ten locals in the United States and had another twenty-two applications pending. By 1940, there were twenty-two actual branches in existence, some of which were located in Latin America and the West Indies; its membership was said to be in the thousands. Considerable funds were raised to help the victims of the war, and to keep open Ethiopian Embassy’s worldwide.

On September 3rd 1937 Law firm of Delaney, Lewis and Williams presents the Charter of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated at the regular Friday meeting of the Ethiopian World Federation, 36 West 135th Street.

“We, the Black Peoples of the World, in order to effect Unity, Solidarity, Liberty, Freedom and Self-determination, to secure Justice and maintain the Integrity of Ethiopia, which is our divine heritage, do hereby establish and ordain this Constitution for the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated.”

Its Aims and Objects being;

(a). To promote love and good-will among Ethiopians at home and abroad and thereby to maintain the integrity and sovereignty of Ethiopia, to disseminate the ancient Ethiopian culture among its members, to correct abuses, relieve oppression and carve for ourselves and our posterity, a destiny comparable with our idea of perfect manhood and God’s purpose in creating us; that we may not only save ourselves from annihilation, but carve for ourselves a place in the Sun: in this endeavour, we determine to seek peace and pursue it., for it is the will of God for man.

(b): To promote and pursue happiness; for it is the goal of human life and endeavour.

(c): To usher in the teaching and practice of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.

(d): To promote and stimulate interest among its members in world affairs, and to cultivate a spirit of international goodwill and comity.

(e): To promote friendly interest among its members, to develop a fraternal spirit among them and to inculcate in its members’ the desire to render voluntary aid and assistance to one another at all times.

(f): To render voluntary aid and protection to its members, without fee or charge for same when in need. And, if necessary, to provide and care for refugees and disabled victims of the Italio-Ethiopian War.

(g): To give concrete material and voluntary aid without fee or charge for the same, to all such refugees and disabled victims and to raise funds by voluntary subscription for the purposes aforementioned. There shall be no charge, fee, beneficiary tax or other assessment upon the members of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated, except for dues, provided for in the Constitution and By-Laws of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated.

(h) To encourage its members to develop interest and pride in Democratic institutions and to promote Democratic principles and ideals. May God help us to accomplish these aims and ideals?

Concerning itself mainly with aiding the thousands of Ethiopian refugees living in Egypt, French Somaliland, Kenya, Sudan, and elsewhere, but possessing broader political objectives than its predecessor, the Ethiopian World Federation became a national organization. Assisted in its recruiting efforts by its weekly tabloid, the Voice of Ethiopia (in which the term “Negro ” was proscribed), the organization conducted propaganda meetings in nearly every American city with a sizeable Afro-American population. It also dispatched members to cities less well populated with blacks to establish locals. It was reported in July, 1938 that the Federation had founded ten locals in the United States and had another twenty-two applications pending. By 1940, there were twenty-two actual branches in existence, some of which were located in Latin America and the West Indies; its membership was said to be in the thousands. Considerable funds were raised to help the victims of the war, and to keep open Ethiopian Embassy’s worldwide.

On September 3rd 1937 Law firm of Delaney, Lewis and Williams presents the Charter of the Ethiopian World Federation, Incorporated at the regular Friday meeting of the Ethiopian World Federation, 36 West 135th Street.

In presenting the Charter, Attorney Delaney said,

“I never dreamed that I would be called upon to serve His Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie. Dr. Bayen has come to this country and has felt out its pulse and was able to accomplish his purpose. He knew what he wanted in the charter; he knew what you wanted — an organ that would encompass the whole world wherever Black People live and he got it. You have a right, a charter, but without the work of each one of you, it will be useless. With this right, there is a responsibility and a duty. It gives me great pleasure to present the Charter.”

Attorney Lewis emphasized the oneness of the Black race everywhere, saying,

“The destiny of the Black man in Ethiopia is just as important to me as the destiny of the Black man in Harlem. A Black man from Jamaica or Trinidad or Georgia is the same. The white man has been trying to divide us on that issue for a long time. I believe in the omnipotence above and in the Bible. I believe that princes shall come out of Ethiopia. I believe that the destiny of the Black man is in the stars and soon will come to the realization of his destiny here on this earth. The difference between Black Americans and West Indians is that on the way from Africa, some of our fore parents dropped off in Jamaica and others came on to the United States.”

Mr Mathew E. Gardner, EWF Chairman said,

“We will profit by the mistakes of the past. In spite of past defeats, the work must go on until freedom is assured. The Ethiopian World Federation is the organisation, not merely an organization. Unity of all Black people in the United States, Africa and elsewhere is our goal. Soon the white man, our oppressor, will realize that the Black man is united.”

The main goal of the Ethiopian world federation Inc. is inherent in its name. The Ethiopian (meaning all black, peoples), World (everywhere), federation (working together).

In presenting the Charter, Attorney Delaney said,

“I never dreamed that I would be called upon to serve His Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie. Dr. Bayen has come to this country and has felt out its pulse and was able to accomplish his purpose. He knew what he wanted in the charter; he knew what you wanted — an organ that would encompass the whole world wherever Black People live and he got it. You have a right, a charter, but without the work of each one of you, it will be useless. With this right, there is a responsibility and a duty. It gives me great pleasure to present the Charter.”

Attorney Lewis emphasized the oneness of the Black race everywhere, saying,

“The destiny of the Black man in Ethiopia is just as important to me as the destiny of the Black man in Harlem. A Black man from Jamaica or Trinidad or Georgia is the same. The white man has been trying to divide us on that issue for a long time. I believe in the omnipotence above and in the Bible. I believe that princes shall come out of Ethiopia. I believe that the destiny of the Black man is in the stars and soon will come to the realization of his destiny here on this earth. The difference between Black Americans and West Indians is that on the way from Africa, some of our fore parents dropped off in Jamaica and others came on to the United States.”

Mr Mathew E. Gardner, EWF Chairman said,

“We will profit by the mistakes of the past. In spite of past defeats, the work must go on until freedom is assured. The Ethiopian World Federation is the organisation, not merely an organization. Unity of all Black people in the United States, Africa and elsewhere is our goal. Soon the white man, our oppressor, will realize that the Black man is united.”

The main goal of the Ethiopian world federation Inc. is inherent in its name. The Ethiopian (meaning all black, peoples), World (everywhere), federation (working together).